Unearth Hidden Stories from African-American History in Digital Archive

David LaFevor, CC BY-SA

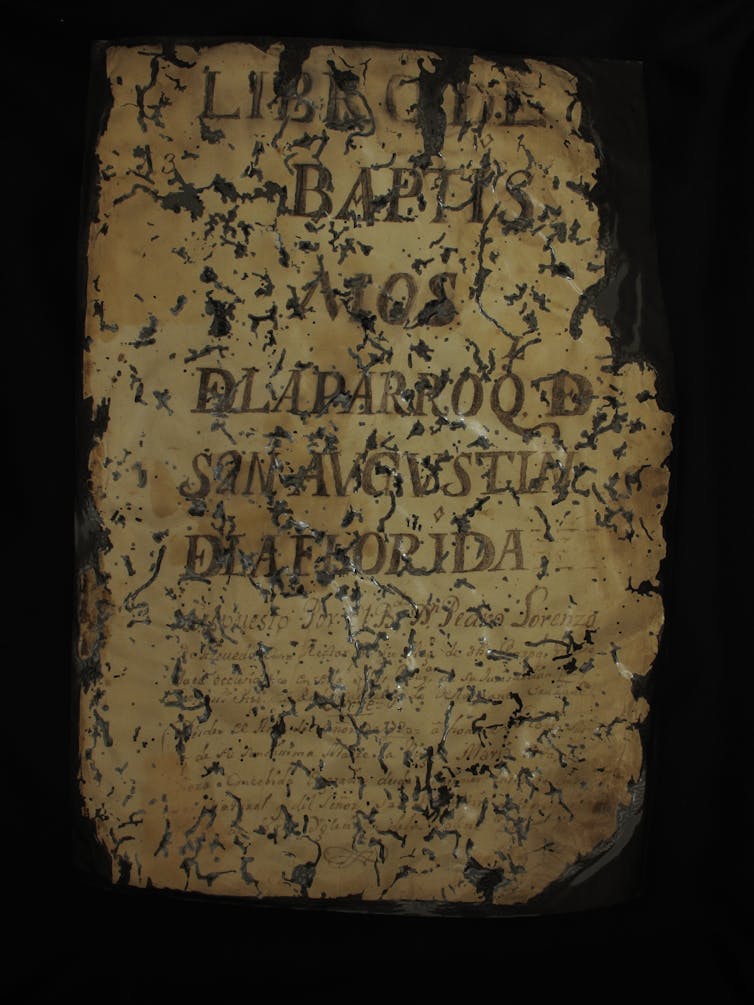

Many years ago, as a graduate student searching in the archives of Spanish Florida, I discovered the first “underground railroad” of enslaved Africans escaping from Protestant Carolina to find religious sanctuary in Catholic Florida. In 1738, these runaways formed Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, the first free black settlement in what became the U.S.

The excitement of that discovery encouraged me to keep digging. After doing additional research in Spain, I followed the trail of the Mose villagers to Cuba, where they had emigrated when Great Britain acquired Florida. I found many of them in 18th-century church records in Havana, Matanzas, Regla, Guanabacoa and San Miguel del Padrón.

Today, those records and others live on in the Slave Societies Digital Archive. This archive, which I launched in 2003, now holds approximately 600,000 images dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries. Since its creation, the archive has led to new insights into African populations in the Americas.

David Lafevor, CC BY-SA

What we’ve found

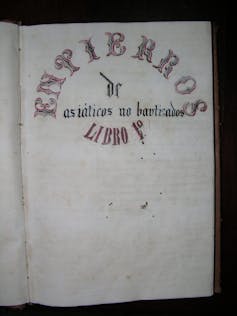

The Slave Societies Digital Archive documents the lives of approximately 6 million free and enslaved Africans, their descendants, and the indigenous, European and Asian people with whom they interacted.

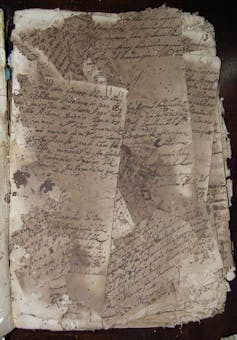

When searching for and preserving archives, our researchers must race against time. These fast-vanishing records are threatened daily by tropical humidity, hurricanes, political instability and neglect.

The work is usually challenging and sometimes risky. Our equipment has been stolen in several locations. Soon after we left the remote community of Quibdó, Colombia, a gun battle erupted in the surrounding jungles between the government military forces and Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, better known as FARC. It’s no wonder that one of our team members called what we do “guerrilla preservation.”

This hard work has allowed us to discover more about the lives of slaves in the Americas. For example, the Catholic Church mandated the baptism of enslaved Africans in the 15th century. The baptismal records now preserved in the Slave Societies Digital Archive are the oldest and most uniform serial data available for African-American history.

Slave Societies Digital Archive, CC BY-SA

These unique documents also offer detailed information regarding the diverse ethnic origins of Africans in the Atlantic world. Once baptized, Africans and their descendants were eligible for the sacraments of Christian marriage and burial, adding to their historical record. Through membership in the Catholic Church, families also generated a host of other religious documentation, such as confirmations, petitions to wed, wills and even annulments.

In addition, Africans and their descendants joined church brotherhoods organized along ethnic lines. These groups recorded not only ceremonial and religious aspects of their members’ lives, but also their social, political and economic networks.

Slave Societies Digital Archive, CC BY-SA

Previously unknown church records for Havana’s black Brotherhood of St. Joseph the Carpenter document the membership of Jose Antonio Aponte, executed by Spanish officials in 1812 for leading an alleged slave conspiracy. Our records similarly document the marriage and death of another famed “conspirator” – the mulatto poet Gabriel de la Concepcion Valdes, better known as Placido.

Africans and their descendants also left a documentary trail in municipal and provincial archives, including petitions, property registries and disputes, bills of sale, dowries and letters from owners granting slaves their freedom.

Sharing our discoveries

My work in the rich records in Florida, Spain and Cuba taught me how to track early African history elsewhere. Additional grants have allowed our archival teams to expand to new sites in Brazil, Cuba and Colombia and, finally, to digitize the church records for Spanish Florida.

Thanks to those records, and the excavations of archaeologist Kathleen Deagan, Mose, the settlement that I first studied as a graduate student, is today a National Historical Landmark. It boasts a new museum where the Fort Mose Historical Society organizes historical reenactments and community events.

Slave Societies Digital Archive, CC BY-SA

Each of the modern nations whose African history we are tracking still struggles with the legacy of slavery. Both scholars and the public who are interested in African heritage can look at these materials to help define national identities in multicultural societies. For example, the Brazilian Constitution of 1988 granted land rights to self-identified quilombolas, or runaway slaves. One group was able to find their ancestors in church records we preserved for the state of Rio de Janeiro.

Since the archive’s inception, we have worked to ensure that these precious materials are freely available to the interested public. Our teams also provide copies of all digitized records to our host churches and archives, as well as donate cameras and other necessary equipment to allow local teams to continue preserving their own endangered history.

Next, we hope to begin a new project in the Dominican Republic, Spain’s first colony in the New World and my childhood home. It boasts many of Europe’s “firsts” in the Western Hemisphere. The capital of Santo Domingo is a UNESCO World Heritage Site where Spaniards established the first monastery, the first hospital, the first court of appeals, the first university, the first cathedral in the Americas – and a free black town that predates Mose, the site where all this work first started.

Credit: Slave Societies Digital Archive, CC BY-SA![]()

Jane Landers, Professor of History, Vanderbilt University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.