by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | May 8, 2020 | Headline News |

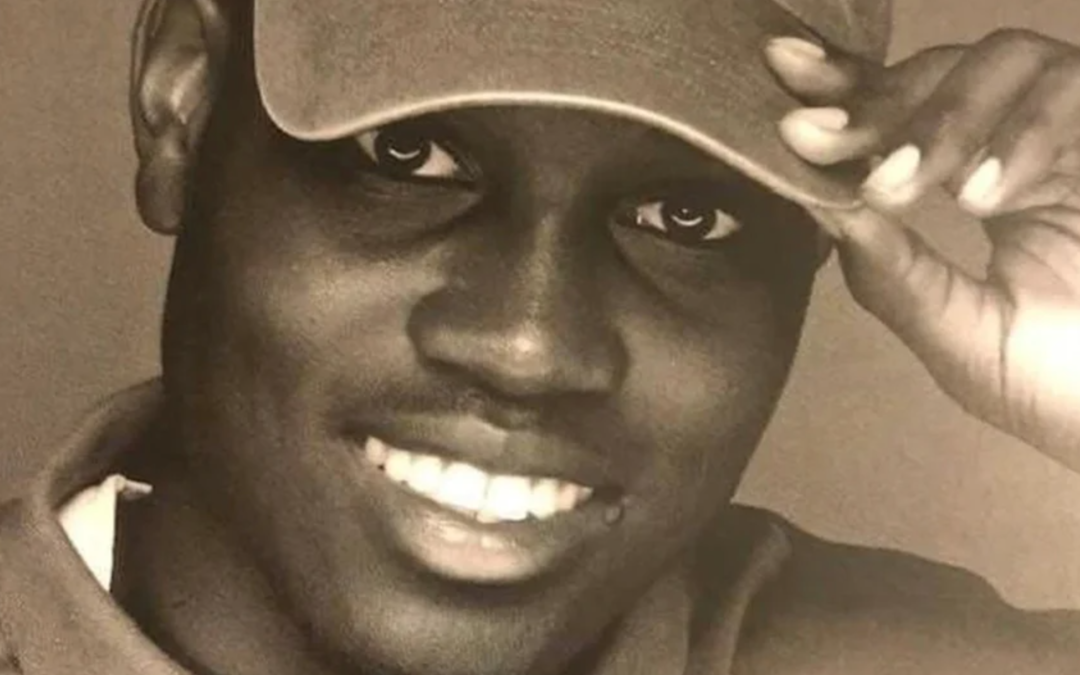

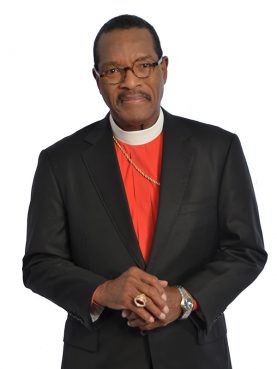

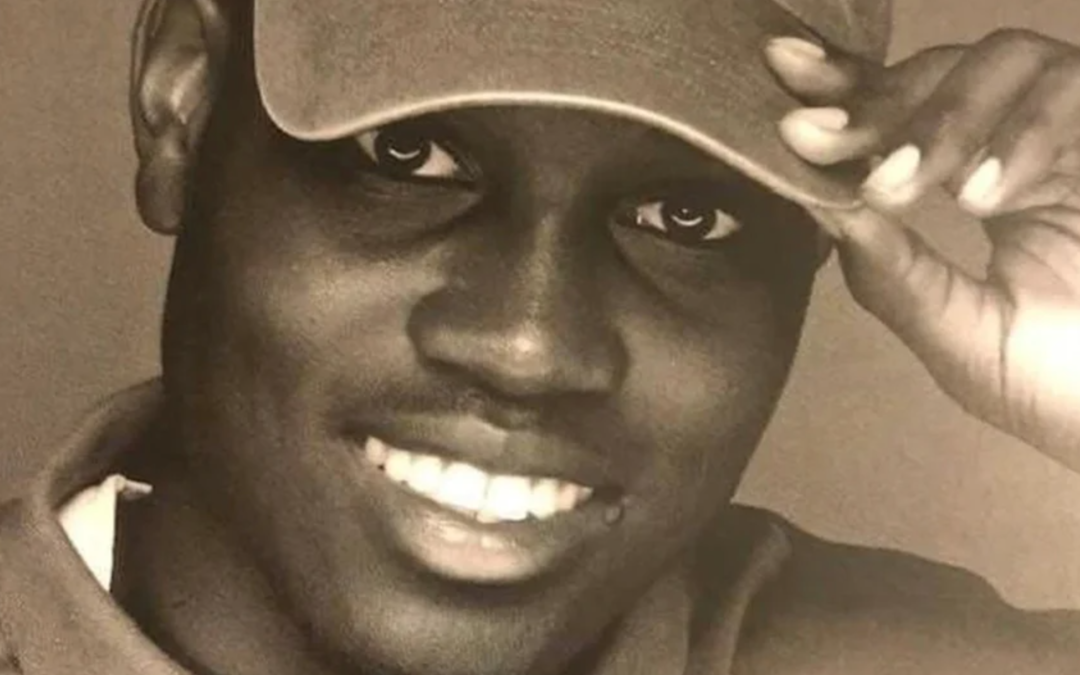

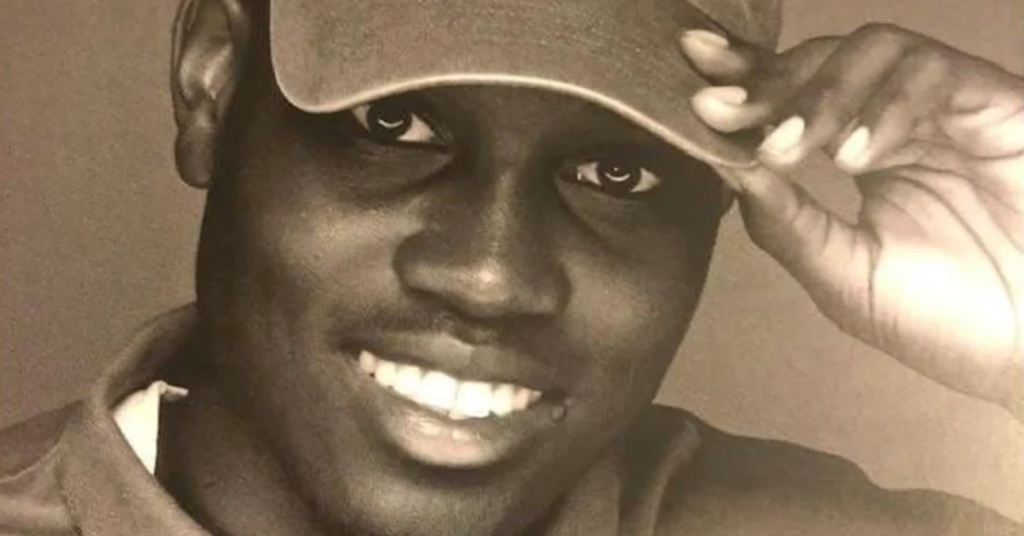

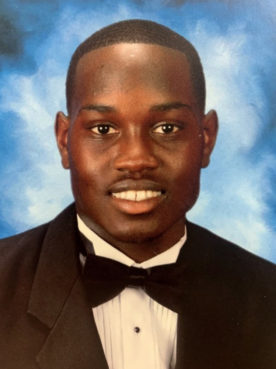

Ahmaud Arbery, in an undated family photo. Courtesy photo

With the release of a viral video months after the shooting of Ahmaud Arbery, a black jogger in Georgia, religious leaders have raised their voices to ask questions about how and why he died.

On Thursday (May 7), the Georgia Bureau of Investigation announced it had charged two white men, Gregory McMichael, 64, and his son, Travis McMichael, 34, with murder and aggravated assault in the case, more than two months after Arbery’s death in Brunswick.

There has been outrage, which grew with the release this week of the cellphone video, that there had been no arrests in the case, which is now being handled by a third prosecutor. The second, District Attorney George Barnhill, told local police: “We do not see grounds for an arrest” in the case. He later recused himself, as did the first prosecutor. The third prosecutor asked the GBI to investigate on Tuesday, and the inquiry began the next day.

According to the GBI, whose investigation is continuing, both men confronted Arbery with firearms. “During the encounter, Travis McMichael shot and killed Arbery,” the agency said.

Hours after tweeting about the felony arrest warrants for the McMichaels, Lee Merritt, a lawyer representing Arbery’s family, tweeted a birthday tribute to Arbery, who would have turned 26 on Friday.

“Happy Birthday #AhmaudArbery,” Merritt said. “You’re bravery in the face of death is humbling and inspiring. I pray the ancestors give us all the strength and courage to #fightlikeAhmaud.”

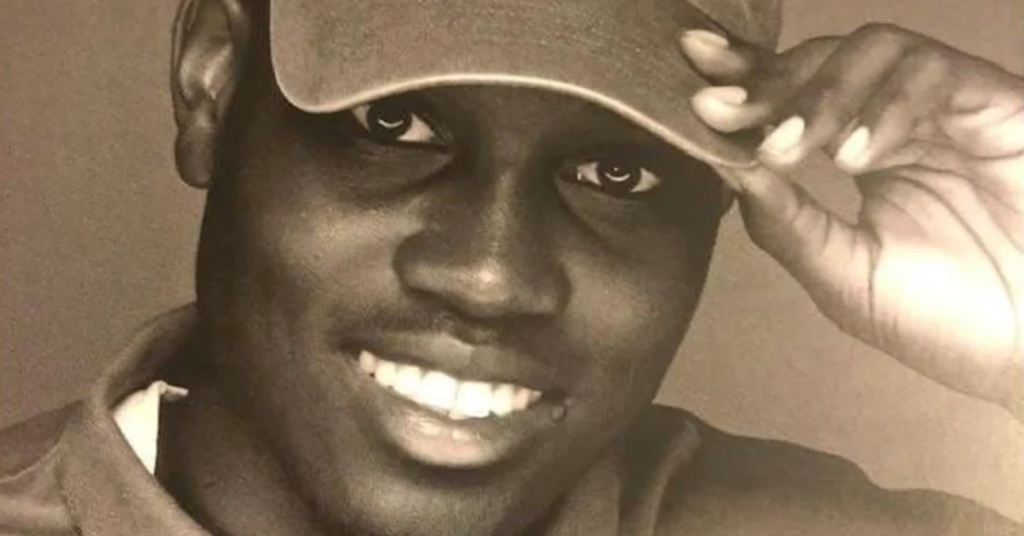

Arbery, a former high school football player heading to become an electrician, died on Feb. 23.

The Rev. Al Sharpton, president of the National Action Network, plans to host an online “call to demand justice” in honor of Arbery on Friday evening, featuring Arbery’s parents and their lawyers.

Here’s a sampling of 10 voices from religious officials, authors and clergy who, across racial and ideological lines, reacted to the video and the arrests and questioned the circumstances of Arbery’s death:

“Ahmaud Arbery’s death is akin to a modern-day lynching. Enough is enough. We demand #JusticeForAhmaud now!”

Russell Moore, president of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission

“There is no, under any Christian vision of justice, situation in which the mob murder of a person can be morally right. … (T)he Bible tells us, from the beginning, that murder is not just an assault on the person killed but on the God whose image he or she bears. Sadly, though, many black and brown Christians have seen much of this, not just in history but in flashes of threats of violence in their own lives. And some white Christians avert their eyes — even in cases of clear injustice — for fear of being labeled ‘Marxists’ or ‘social justice warriors’ by the same sort of forces of intimidation that wielded the same arguments against those who questioned the state-sponsored authoritarianism and terror of Jim Crow.”

Austin Channing Brown, author of “I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness.”

Ahmaud Arbery, in an undated family photo. Courtesy photo

“I will not dig for evidence; today we are going to assume all that is true about Arbery. Because Arbery is one person in a centuries old line of Black people who must prove they are human in order to call their murders unjust. … Lynchings are still here, but so are we. They haven’t been able to destroy us. The fear hasn’t kept us from showing up, from experiencing joy, from demanding more from America.”

Andy Stanley, founder of Atlanta-based North Point Ministries

“I’ve been advised not to post about the murder of Ahmaud Arbery until I calm down a bit. But that’s part of the problem, isn’t it? We calm down and go on about our business. This must end. Our black brothers and sisters need white advocates to bring this to an end. Count me in!”

Jemar Tisby, author of “The Color of Compromise: The Truth about the American Church’s Complicity in Racism”

“This will not be popular with some, but putting these men in cages won’t change much. These men and Ahmaud’s family need restorative justice. There needs to be healing (to the extent possible with such a crime) and not just incarceration.”

Pastor Jentezen Franklin, leader of Free Chapel, an evangelical megachurch in Gainesville, Georgia

“After viewing this video, there’s one thing that should be crystal clear now to all Georgians: the authorities must expeditiously complete their investigation of the circumstances surrounding the death of Ahmaud Arbery and take all appropriate measures in response to what appears to be a horribly heinous crime. I am calling upon the authorities to act now; COVID-19 cannot be an excuse for injustice.”

“Georgia Muslims were dismayed and infuriated but not surprised by the video showing the modern-day lynching of Ahmaud Arbery. We strongly condemn this racist act of unjustified murder, which is part of a pattern of violence rooted in the historic subjugation of African-American men and women. We join the call for the arrest of the two suspects prior to the convening of the grand jury.

“These dangerous episodes targeting the African-American community are not unique, but rather are symptomatic of the racism that instills fear and distrust within our communities. It is long past time for law enforcement to take such crimes seriously.”

“Do not dream lynchings do not take place in the year of our Lord 2020.

Unarmed but not unnamed.

His name is Ahmaud Arbery.

He was 25 years old.

On a jog.

‘PURSUE JUSTICE.’ Isaiah 1:17”

David French, senior editor of The Dispatch

“When Arbery was confronted by armed men who moved directly to block him from leaving, demanding to ‘talk,’ then Arbery was entitled to defend himself. Georgia’s ‘stand your ground law’ arguably benefits Arbery, not those who were attempting to falsely imprison him at gunpoint.

“It’s also worth remembering that the long and evil history of American lynchings features countless examples of young black men hunted and killed by white gangs who claimed their victims had committed crimes.”

“In the presence of the kind of cancerous hatred that killed #AhmaudArbery, the kind that is having a renaissance here in America, there are only two kinds of white Americans: there are white racists and there are white anti-racists.”

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | May 2, 2020 | Headline News |

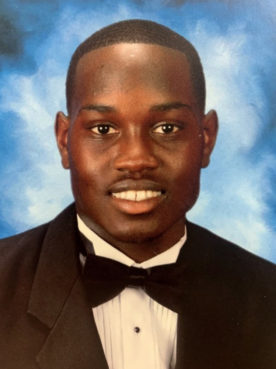

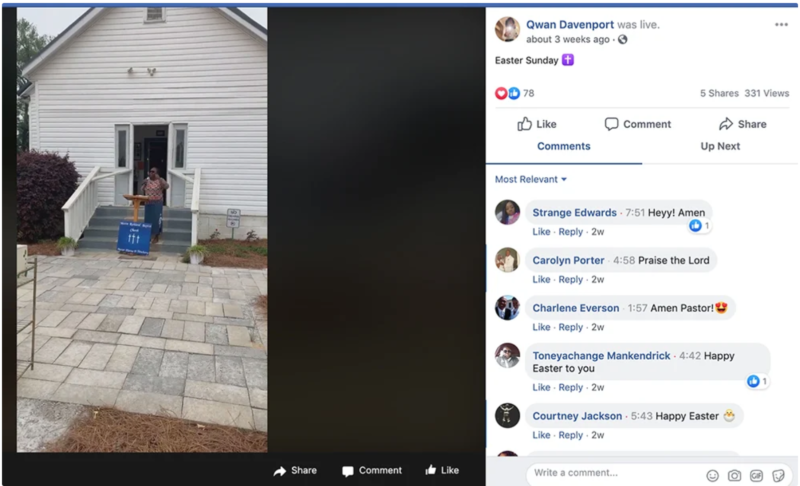

Pastor Florine Newberry delivers her Easter Sunday message from the doorway of Mattie Richland Baptist Church, April 12, 2020, streamed via Facebook Live in Pineview, Georgia. Video screengrab via JaQwan Davenport

When Pastor Florine Newberry of Mattie Richland Baptist Church in rural Pineview, Georgia, realized her congregation wouldn’t be able to meet in the church’s blue carpeted sanctuary due to the coronavirus pandemic, “I just saw the sheep scattering,” she said.

Many of the 45 to 50 members of Newberry’s independent church do not have computers or home access to the internet. Though some own cellphones, cellular service is often spotty in the rural flats more than two hours south of Atlanta.

Her worst fears were quieted when some parishioners took to gathering 6 feet apart in their cars on sunny Sundays to hear Newberry preach.

But once Mattie Richland Baptist became one of 46 predominantly black churches in Georgia to receive help gaining internet access from Fair Count, an organization founded to increase participation in the 2020 census in hard-to-count areas, Newberry’s great-nephew — and Sunday school teacher — said he could use his phone to livestream her sermons.

Pastor Florine Newberry. Courtesy photo

When Newberry preached her Easter sermon from the doorway of her church, her message was viewed by hundreds of people via Facebook Live thanks to the Fair Count hot spot.

“That hot spot from Fair Count, and through the blessings of God that watches over Mattie Richland, has allowed me to have peace of mind that I can still reach out to people,” said Newberry.

America’s black clergy, like their counterparts in houses of worship across the country, have heard the call to pick up the tools of Zoom, Facebook and other social media as a workaround for in-person worship and Bible study. But with issues of access and technical ability among some congregants, and a pandemic that has closed their church doors and scattered congregations, African Americans have been scrambling to sustain crucial connections to their houses of worship.

“If you look at websites, Facebook, other media, white churches are better positioned, it seems, to connect their people and to connect to their people than black churches going into this crisis,” said Mark Chaves, director of the National Congregations Study, citing data from 2018-19.

That advantage has widened the religious digital divide. A new survey from Pew Research Center shows that while 92% of evangelical Christians and 86% of mainline Protestants say their church offers streaming or recorded services online, only 73% of Protestant worshippers in the historically black tradition say they can watch religious services remotely.

Sunday school teacher JaQwan Davenport, left, works with youth on a donated laptop at Mattie Richland Baptist Church, in Pineview, Georgia, before social distancing was required to combat the coronavirus. Courtesy photo

Access to digital resources is not solely a problem in rural areas. The Rev. Boise Kimber, senior pastor of First Calvary Baptist Church in New Haven, Connecticut, has worked to get churches websites since 2016. But during the pandemic, Kimber initially chose not to use livestreaming, knowing many of his inner-city church members did not have access to a computer. His church later added Zoom as another option to reach younger members.

“I’m trying to reach individuals that support our ministry, spiritually and financially,” said Kimber. Those people, he said, are available largely by phone.

Pastor Brenda Lacy, leader of Greater Revelations Worship Center, a multicultural inner-city church in Kansas City, Missouri, said she knew her 50 members, including the elderly, could be reached via conference calls on their phones because it was how they gathered remotely for prayer calls three times a week.

“I’m not sure if every member has internet access, but they do have access to the conference line,” she said. “The only thing that has changed with that is that we’re doing our morning worship on there, we’re doing our Bible studies on there, we’re doing everything there.”

Nona Jones. Courtesy photo

Nona Jones, head of Facebook’s global faith-based partnerships, said Facebook has seen a “pretty major spike in the spiritual pages” used by faith communities in recent weeks. Sensitive to those limited to phones, Facebook has begun making available a free service that allows churches to provide a phone number for people who do not have reliable internet or strong bandwidth to view a livestream.

“The feedback we’ve heard so far, even using it in our own church, is that there’s a lot of older people who have felt connected who were feeling isolated,” said Jones, who in addition to her Facebook job is co-pastor of a church in Gainesville, Florida. “But being able to even listen to our voices has given them a sense of hope and a feeling of community.”

The elderly are most at risk and least likely to be able to link to their churches online.

“There is definitely some exclusion that’s taking place when it comes to older congregants, especially those who used to get picked up by the bus and brought into worship,” said Elonda Clay, a Ph.D. candidate in theology and religious studies who has studied the black church and technology trends.

Elonda Clay. Photo by Dirk van der Duim

Clay pointed to her 80-year-old father, a longtime member of a “small United Methodist church of 80-year-olds,” who was only able to phone into a Sunday worship conference call after someone called him to inform him the first one had occurred.

Some churches have found that improving their internet connections can also improve their spiritual connections with a younger generation. “As younger people are not going to service in the same numbers that, say, the baby boomer generation went,” said the Rev. Barbara Williams-Skinner, co-convenor of the National African American Clergy Network, “streaming is the ideal way — this is pre-COVID — for reaching younger church people.”

If nothing else, the pandemic is showing many churches the power of the internet, whatever their bandwidth. Brother Marcus Tolliver of Browns Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Chester, South Carolina, said that coronavirus has prompted a sea change in his church, which previously used its Facebook page to post daily phrases of inspiration and photos from church events. If a service was recorded, it would be distributed on DVDs or CDs.

Last week, he led his congregation of 275 in a two-night online revival, using his iPhone when the internet service proved to be poor at the church.

Brother Marcus Tolliver, bottom right, of Browns Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, moderates a “Focusing on the Mind” panel via Zoom and Facebook Live on April 25, 2020. Video screengrab

The next day, Tolliver moderated on Zoom and Facebook a “Focusing on the Mind” panel on black churches and mental health that drew more than 2,400 views. On Sunday (April 26), the church converted its annual “pack-a-pew” service to “pack-a-page” on Facebook Live, with more than 1,000 views.

“This is definitely new territory,” said Tolliver. “We’ve learned to do things that we never thought we’d do. Some of these older preachers in the more rural communities, they’ve learned to work technology they never expected that they would have to work. They’ve learned how to have Zoom meetings with their church families, and they’ll have Bible study and they can still see each and every one of their members. Before COVID-19, that wasn’t even a thought.”

Jeanine Abrams McLean. Courtesy photo

For Georgia churches like Mattie Richland Baptist, the efforts of Fair Count, founded in Atlanta by former Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, have shown how improving internet access for churches can be a boon to the entire community, sometimes in unexpected ways.

Jeanine Abrams McLean, vice president of Fair Count and Stacey Abrams’ sister, said the organization has established 135 internet access points using hot spots and tablets donated to churches, barbershops and community centers across Georgia, where about 20% of people have only broadband access or lack internet entirely.

Besides internet access, McLean said, the nonprofit, backed by grants from foundations and private donors, has begun providing free church management software that clergy can use to communicate with members and to facilitate online giving.

“Even if a church doesn’t have internet access, if we’re able to give it to a pastor that has internet access, then they can send out text messages to their parishioners that way,” McLean said of the program that has aided a few dozen houses of worship from Nevada to Mississippi to Illinois. She hopes to extend the service to several hundred more over the next four years.

After receiving a Fair Count hot spot, the Rev. Bo Barber II, pastor of Prospect African Methodist Episcopal Church in Fortson, a suburb of Columbus, Georgia, saw that it could help with more than the census.

The Rev. Bo Barber III, of Fortson, Georgia, speaks in Atlanta at a May 2019 “Black Men Count” event about the 2020 census. Courtesy photo

“When the schools closed, there were a number of children that needed to have access to broadband in the communities and in the area,” Barber said. Now, he explained, “our community can drive up into the parking lot” and draw connectivity from their cars. In the last few weeks, 40 families have visited the church lot.

“Knowledge is power,” said Barber. “And if you’re isolated, you’re not empowered.”

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Apr 29, 2020 | Headline News |

The virtual choir of Grace Baptist Church performs ‘I Am Thine,’ which was included in the April 19, 2020, online service from the Mount Vernon, New York, church. Video screengrab

Top officials of seven black Christian denominations have joined civil rights leaders in calling for people to stay home until it is safe in states whose governors are lifting shelter-in-place orders.

“We regard this pandemic as a grave threat to the health and life of our people, and as a threat to the integrity and vitality of the communities we are privileged to serve,” they wrote in a statement released Friday (April 24). “For these reasons, we encourage all Black churches and businesses to remain closed during this critical period.”

The signatories include leaders of the African Methodist Episcopal Church; African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church; Christian Methodist Episcopal Church; Church of God in Christ; National Baptist Convention of America, International, Inc.; National Baptist Convention, U.S.A. Inc.; and Progressive National Baptist Convention Inc.

Some of those denominations have tallied or been the subject of reports of COVID-19 deaths among their clergy and members.

“The denominations and independent churches represented in this statement, which comprise a combined membership of more than 25 million people and more than 30,000 congregations, intend to remain closed and to continue to worship virtually, with the same dedication and love that we brought to the church,” they added.

The denominational officials and faith leaders, including the Rev. W. Franklyn Richardson of the Conference of National Black Churches and the Rev. Al Sharpton of the National Action Network, joined presidents of the NAACP, the National Urban League and other groups as signatories.

They noted that an April 21 report by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated that 20% of the COVID-19 deaths in the United States were of African Americans. In comparison, blacks constitute 13% of the U.S. population.

“Across the country, we see the same disproportionate impact,” they said. “Our families need us. Our communities need us. We must continue to telework wherever possible, and to tele-worship for however long it is necessary to do so.”

The letter comes in the same week the conservative law firm Liberty Counsel has organized a “ReOpen Church Sunday” initiative, encouraging clergy to begin in-person worship again on the weekend of May 3. That Sunday falls in the same week as the annual observance of the National Day of Prayer.

According to The Hill, some governors have never issued stay-at-home orders, others’ mandates are expiring within days, and still, others stated no end date.

Likewise, states have varied widely in their decision to have or not have religious exemptions in their orders about staying at home.

The black church officials and civil rights advocates said they understand some people may believe they need to be involved in public life. The leaders urged those who do to follow precautions about physical distancing and wearing masks.

“We do not take it lightly to encourage members of our communities to defy the orders of state governors,” they added. “But we are compelled by our faith, by our obligation as servants of God, and by our commitment as civil rights leaders, to speak life into our communities. Our sacred duty is to support and advance the life and health of Black people, families, and communities in our country.”

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Apr 16, 2020 | Headline News |

The Rev. Frank Williams has been so busy leading two black churches in the New York borough of the Bronx that he hadn’t really considered the full extent of COVID-19’s impact on his congregation, his family and his community.

But when asked, the Southern Baptist pastor of two churches, each with more than 200 members, realized after four weeks the list was long:

The Saturday before Easter, a beloved deacon — a decades-long friend who had been the property manager, the men’s ministry leader and the person who ran the van ministry picking up seniors for Bronx Baptist Church — died from complications related to COVID-19.

The Rev. Frank Williams pastors two black churches in the Bronx. Courtesy photo

Williams’ wife, a hospital residency coordinator, and his three children, all under the age of 12, have recovered from COVID-19 and he preached his first online sermons from the Psalms while quarantined.

The 47-year-old pastor helped the staff of Wake-Eden Community Baptist Church’s elementary school shift to remote learning and, as the need for food in the nearby community increased, worked to provide families with food that previously would have been prepared for their children at a church day care.

“The impact is very real for us, not just here in New York, but very real for us as a congregation,” said Williams, a St. Kitts native whose churches include black Americans and immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean.

Across the country, black clergy say the coronavirus is touching — and sometimes taking — the faithful who until a month ago were accustomed to meeting weekly in their pews. Some are mourning losses in the highest echelons of their denomination. Others are counting the dead, sick and unemployed.

And some African American pastors are joining forces to demand the Trump administration and congressional leaders take actions ranging from setting up testing sites in black and poor communities to providing masks to low-wage essential workers, prisoners and people living in homeless shelters.

The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently released a March report that showed 33% of hospitalized patients in a 14-state study were African American; comparatively, blacks constitute 13% of the U.S. population.

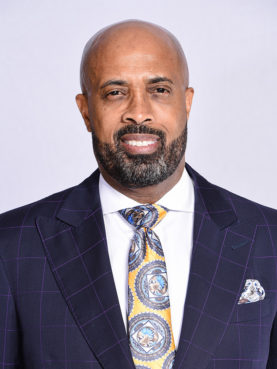

The Rev. Jessica Ingram and Bishop Gregory Ingram. Courtesy photo

At least one historic black denomination has started a preliminary tally of the toll of COVID-19.

Bishop Gregory Ingram leads the African Methodist Episcopal Church’s First Episcopal District, which includes the hard-hit areas of New York, and asked presiding elders within it to report what they knew about members’ health and economic statuses. A Wednesday (April 15) report shows that throughout the district, which also includes churches in states such as New Jersey and Delaware, 48 members have died, 258 have been infected and 1,913 have become unemployed as a result of COVID-19.

“I had one church that lost three members in one day,” Ingram said, referring to a congregation in Freeport, Long Island.

Another of the deceased from the AME denomination is Yonkers pastor Scott Elijah, who died in late March. He was remembered not only by his small church but by Local 100 of the Transport Workers Union, which recalled his work with NYC Transit in a “Lost to Coronavirus” listing: “The entire Track Division is in mourning.”

Pastor Scott Elijah from Yonkers, New York. Photo courtesy of TWU Local 100

Ingram and his wife, the Rev. Jessica Ingram, have been praying on 6 a.m. daily calls with members of their district and following up by phone with church members who have lost loved ones to COVID-19.

“This is new territory for us,” said his wife, who as the episcopal supervisor for the district has been co-hosting Zoom meetings with leaders among the young adults, laity and pastors in the district. The training and study sessions have centered on topics ranging from the “new landscape of the church” to health disparities. “And we don’t have answers, so basically I just express my prayers for them and listen and let them know that we are here for them.”

The Church of God in Christ, another historic black denomination, has reportedly lost close to a dozen of its bishops and other leaders to COVID-19, including Bishop Phillip Aquilla Brooks II, who was the Michigan-based first assistant presiding bishop.

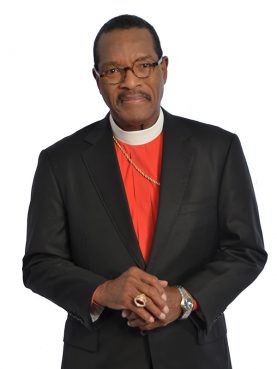

Church of God in Christ Presiding Bishop Charles E. Blake Sr. Photo courtesy of COGIC-PR

“The loss of such a respected visionary leader cannot be verbally expressed,” said COGIC Presiding Bishop Charles Blake in a video announcement that did not specify Brooks’ or others’ cause of death. “I know that the death of Michigan Bishop Brooks, Nathaniel Wells and so many others has caused great concern and great pain throughout the church, concern for our leaders and concern for the future of the church.”

After noting that he and his family were well, Blake spoke of divine pledges and the need to lean on God.

“At this challenging time, I want you to remember that God has promised that the gates of hell shall not prevail against his church,” he said in the announcement on the homepage of COGIC’s website. “And I’m absolutely confident that God is going to bring us through this tough time together. We as people of faith must look to God and to the word of God as we have in challenging times past for hope and for encouragement.”

At a video news conference hosted Wednesday by the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference and Repairers of the Breach, black clergy called on leaders at the White House and in Congress to provide more resources to African Americans and to focus more on humanity than the economy.

“Black people are more likely to be essential workers, keeping us safe and fed,” said the Rev. William Barber II, president of Repairers of the Breach. “But these are the very people the stimulus bill did not provide (with) the essentials of health care, living wages or even guarantee that no water would be shut off. While corporations in less than three weeks got $2.5 trillion.”

Clergy on the call spoke of praying over the phone with health care workers in their congregations who lack protective equipment and people who can’t pay their rent.

“There is no sheltering in place when there is no shelter,” said Bishop Yvette Flunder, a San Francisco preacher affiliated with the Metropolitan Community Churches and who oversees a ministry site that provides food, medical and housing case management services.

The Rev. Traci Blackmon, a justice executive minister for the United Church of Christ and leader of a church north of St. Louis, said her congregation includes bus drivers, grocery workers and mail carriers. She said five of about 80 congregants tested positive for COVID-19 and three went to the hospital multiple times before they could get tested, thus exposing their households in the meantime.

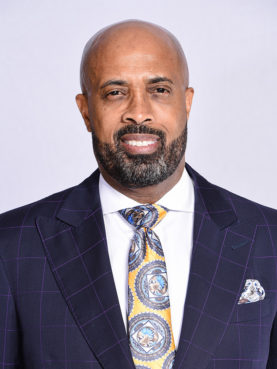

The Rev. Frederick Haynes III. Photo by Jack Akana Jr.

“I pastor people who are now seeking food for their children and for their families because those food services have had to be suspended because of the deaths of two bus drivers who died from COVID-19,” she said.

The Rev. Frederick Haynes III, pastor of Friendship-West Baptist Church in Dallas, opened Wednesday’s videoconference with an “appeal to those in power on behalf of communities in pain and in grief.” In a separate interview, he noted that black community leaders who have been concerned about environmental justice and health disparities will now have to see what more the black church can do.

“There are those of us who have been fighting for that and now we are upgrading our fight because we are seeing that this country has proven that it does not have a desire to protect us,” he said.

News reports have indicated other examples of how the coronavirus has ended the lives of longtime churchgoers and clergy from Louisiana to Maryland to New York City’s Harlem borough. A Virginia pastor who claimed “God is larger” than the coronavirus succumbed to it, his church announced.

Clergy tasked with memorializing people who have died, often unexpectedly, say the coronavirus has prompted uncharacteristic changes in funeral and burial traditions.

The Rev. Adolphus Lacey, pastor of Bethany Baptist Church in Brooklyn, said Tuesday that his 900-member congregation has had three confirmed COVID-19 deaths. He officiated at two funerals the day before, one at a Brooklyn funeral home and one an hour-and-45-minute drive away in New Jersey.

Though familiar with the rites of death, Lacey said wearing masks, gloves and keeping socially distant has made the moments of farewell even more difficult.

One funeral, for a popular usher, was carried out on Zoom and so many wanted to participate, some never got past the virtual waiting room.

Bronx Baptist Church in New York. Courtesy photo

“The sad part, I said, he was at everybody else’s funeral but when it came to his funeral, nobody could be there but just his family,” said Lacey, whose church is affiliated with the Progressive National Baptist Convention Inc. and the National Baptist Convention U.S.A. Inc.

From his New York borough north of Lacey’s, Williams spoke of his longtime faith helping him cope with the sadness and hang on to hope.

“There are always people who experience loss and that’s the reality of grief,” said Williams. “We are experiencing that in the loss of our deacon but we are still praying for God’s preservation. And that really comes from Psalm 121, where it says ‘I will preserve you from all evil. I will preserve your soul.’”

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Mar 10, 2020 | Entertainment |

Laurie Crouch, from left, Kirk Franklin, Pastor Robert Morris, Pastor Tony Evans, and Trinity Broadcasting Network President Matt Crouch meet in early March 2020. Photo courtesy of Trinity Broadcasting Network

Gospel singer Kirk Franklin, in a discussion to be broadcast this week on Trinity Broadcasting Network, called on white Christian leaders to move beyond “kumbaya moments” and to speak from the pulpit when black people are the subjects of “social injustice happening in the streets.”

Franklin made his remarks on TBN’s “Praise” show in a conversation with the network’s president, Matt Crouch, and Dallas pastors Tony Evans and Robert Morris. Their talk is scheduled to air at 8 p.m./7 p.m. Central on Thursday (March 12) on the Christian network.

The conversation stemmed from Franklin’s announcement in the fall that he would boycott the Gospel Music Association’s Dove Awards after comments he made about race and police shootings during the GMA’s Oct. 15 awards show were edited from the show’s broadcast on TBN. Franklin, who also said that he would boycott TBN and the GMA, said that similar editing occurred when the 2016 show aired.

“This is not a conversation of me attempting to make white people feel bad for being white,” Franklin said at the start of the “Praise” show. “It is to give a bigger perspective on the heartbreaks and the hurts, that black and brown people in America are looking for the church to be a safe haven but at times it isn’t always answering to that call.”

Franklin recounted how earlier in his career a verse he wrote for a song he co-wrote with TobyMac, a white member of the Christian rap trio dcTalk, and Mandisa, a black Christian singer, was left out of the recording that played on Christian radio.

“I believe that black and brown people in this country continuously feel like they’re edited out,” Franklin said.

Minutes later, Crouch beckoned Franklin into a hug.

“Whatever happened, I want to personally apologize so that we get past this, and this program, and others like it in the future, make progress,” Crouch said. “I want to profoundly thank you for helping us understand an issue that maybe some people don’t, including us, including Robert and I.”

Crouch, who is white, also thanked Franklin for “putting this together.”

But Franklin chose not to let the moment where the two men hugged and expressed love for one another pass without clarification. He noted that “this embrace as brothers” came after off-camera discussion.

“I do know that for a lot of black and brown people, just even the optics of what just happened can be very problematic, because throughout history a lot of times white people have sometimes come across that the issues are fixed with the kumbaya moment,” Franklin said. “The kumbaya moment is really, for this generation, is antiquated.”

Evans, whom Franklin has said he consulted before making his boycott decision, described “decade after decade” of personal experiences with racism, including applying to a seminary at a time when some theological schools would only admit blacks on a “probation” status. Evans said he later was excluded from a Christian radio network because, he was told, “it would offend too many of my white listeners.”

He cited an “absence of equity,” in which the emphasis in some churches is that the “life of the unborn matters.

“But when they hear about other groups calling for other lives mattering there is a negative response,” Evans continued. “And while it is maybe legitimate to have a negative response about methodology, there should not be a negative response about mattering.”

Morris, founding lead senior pastor of Gateway Church, said he’d known Franklin for years but had not heard the story of his verse being omitted.

“When you hear this as a white Christian, your heart should break; it absolutely should break,” said Morris of Franklin’s story and other instances of racial injustice. “And then you should say to your brothers, ‘How can I be a part of the solution?’”

Morris, who, like Evans, has his own program on TBN, later said that if white clergy aren’t already discussing race in their pulpit, they should begin, as he has in recent years.

“I started teaching our people about a lack of understanding, and you don’t know that you’re prejudiced but you probably are,” he said.

Franklin noted that evangelist Billy Graham at one time criticized the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. but later worked to integrate his crusades.

“We need to be able to see where the mistakes are, and to be willing to acknowledge them and to be agents of change,’’ Franklin said, “because if you’re not willing to get your feet and hands dirty on this issue, especially this issue, it won’t be anything but kumbaya.”