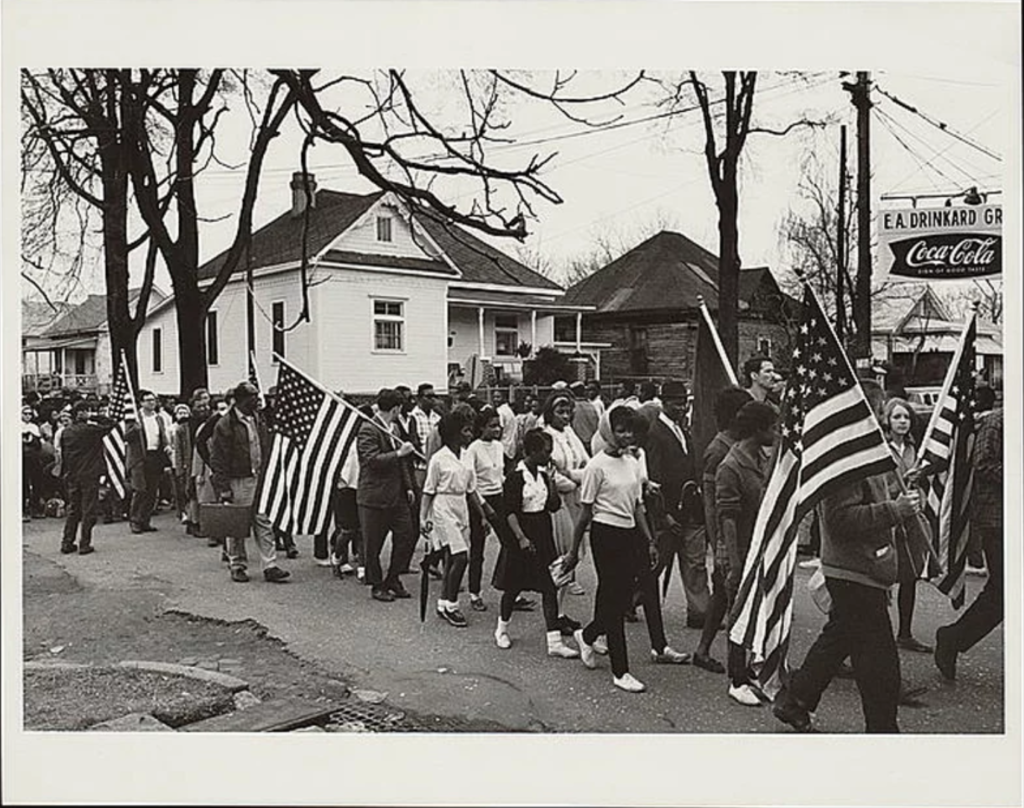

Participants, some carrying American flags, march in the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in 1965. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

The images of that day in 1965 were quickly seared into the American consciousness: helmeted Alabama state troopers and mounted sheriff’s possemen beating peaceful civil rights marchers in Selma, Ala., as clouds of tear gas wafted around the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

On March 7, 1965 — a day that would become known as “Bloody Sunday” — 600 marchers heading east out of Selma topped the graceful, arched span over the Alabama River, only to see a phalanx of state and local lawmen blocking their way on U.S. Highway 80.

The police stopped the marchers, led by Hosea Williams of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and John Lewis, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and ordered them to disperse. Then they attacked. Lewis, one of 58 people injured, suffered a skull fracture. Amelia Boynton Robinson, then 53, was beaten unconscious and left for dead, her face doused with tear gas.

Photos of that terrible day were seen around the world. Historians credit the beatings, and the public outrage that followed, as a catalyst for the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

“The marchers thought they would only be arrested,” says Gary May , a history professor at the University of Delaware and author of “Bending Toward Justice: The Voting Rights Act and the Transformation of American Democracy.” “They thought there would be no major trouble. That night, the film of what happened reached New York, and ABC broke it at 9 p.m.

“People across the nation were shocked at what they saw. LBJ called it a turning point in American history. He compared Bloody Sunday to Gettysburg and Lexington and Concord.”

That day on the bridge was the culmination of a long chain of events, says Alston Fitts, a Selma resident and local historian. He chronicles the history of the city in his book “Selma: Queen City of the Black Belt.”

The Dallas County (Ala.) Voters League and the SNCC had been trying for a year to register blacks to vote. The focus of the struggle was the county courthouse, where protesters went in a vain effort to register. Confrontations occurred when Sheriff Jim Clark denied them entry to the building. It was his mounted possemen on the bridge that day in March 1965.

“A local judge had entered a ruling that outlawed any meeting of more than three people where voting rights were being discussed,” Fitts says. “Leaders in the Selma movement invited the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to come to Selma to take part in the movement. They knew the involvement of Dr. King would bring national attention to Selma. And they knew he would bring expertise on how to stop the stifling tactics being brought to bear against the movement.”

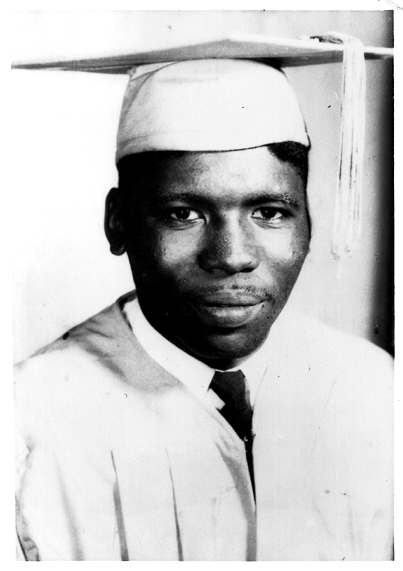

Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot by a state trooper during a nighttime civil rights march in Marion, Ala. Jackson died a few days later. Photo courtesy of Southern Poverty Law Center

But King was not part of the Bloody Sunday march. In February, King had become “discouraged” about the efforts in Selma, May says. “There hadn’t been the event that would capture the attention of the press and consciousness of the country.”

That changed on Feb. 16, May says, when C.T. Vivian, one of the movement’s leaders, had an altercation with Clark on the grounds of the courthouse. Then, on Feb. 18, Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot by a state trooper during a nighttime civil rights march in Marion, a town in neighboring Perry County. Jackson died a few days later.

“That was the impetus of the first march, the Bloody Sunday march,” May says. “Several members of the movement in Selma wanted to carry Jimmie Lee Jackson’s body to Montgomery and deliver it to Gov. George Wallace,” a virulent civil rights foe.

Robinson, a Selma activist then known as Amelia Boynton, had helped SNCC protest against white registrars who kept blacks from voting. Her home was used as a headquarters to plan the march.

After the beatings, “the nation came to Selma,” Fitts says. “The suffering of those marchers crossing that bridge into ‘enemy territory’ captured the attention of the country.”

King led a “symbolic” march to the now-infamous bridge on March 9, then led a full-scale march on March 21 from Selma to Montgomery after U.S. District Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. ordered protection for the demonstrators.

At the start, there were 3,200 marchers, according to the National Park Service. Marchers traveled 12 miles a day, sleeping in fields before reaching Alabama’s capital city on March 25. By then their ranks had swelled to 25,000.

In August, the Voting Rights Act was signed into law.

“Of course, the Selma-to-Montgomery march was important, but Bloody Sunday was the critical mass,” May says. “Many people dropped what they were doing and came to Selma in the wake of the attacks and beatings that occurred that day.

“It put the voting rights bill at the top of the agenda in Washington. It accelerated everything.”