The soundtrack of the Sixties demanded respect, justice and equality

The Supremes, with their polished performances and family-friendly lyrics, helped to bridge a cultural divide and temper racial tensions.

When Sly and the Family Stone released “Everyday People” at the end of 1968, it was a rallying cry after a tumultuous year of assassinations, civil unrest and a seemingly interminable war.

“We got to live together,” he sang, “I am no better and neither are you.”

Throughout history, artists and songwriters have expressed a longing for equality and justice through their music.

Before the Civil War, African-American slaves gave voice to their oppression through protest songs camouflaged as Biblical spirituals. In the 1930s, jazz singer Billie Holiday railed against the practice of lynching in “Strange Fruit.” Woody Guthrie’s folk ballads from the 1930s and 1940s often commented on the plight of the working class.

But perhaps in no other time in American history did popular music more clearly reflect the political and cultural moment than the soundtrack of the 1960s – one that exemplified a new and overt social consciousness.

That decade, a palpable energy slowly burned and intensified through a succession of events: the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963, the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War.

By the mid-1960s, frustration about the slow pace of change began to percolate with riots in multiple cities. Then, in 1968, two awful events occurred within months of each other: the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy.

Through it all, there was the music.

Coming of age during this time in Northern California, I had the opportunity to hear some of the era’s soundtrack live – James Brown, Marvin Gaye, The Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix and The Doors.

At the same time, virtually everyone in the African-American community was directly connected in some way or another to the civil rights movement.

Every year, I revisit this era in an undergraduate class I teach on music, civil rights and the Supreme Court. With this perspective as a backdrop, here are five songs, followed by a playlist that I share with my students.

While they offer a window into the awakening and reckoning of the times, the tracks have assumed a renewed relevance and resonance today.

“Blowin’ in the Wind,” Bob Dylan, 1963

First made a hit by the folk group Peter, Paul and Mary, the song signaled a new consciousness and became the most covered of all Dylan songs.

The song asks a series of questions that appeal to the listener’s moral compass, while the timeless imagery of the lyrics – cannonballs, doves, death, the sky – evoke a longing for peace and freedom that spoke to the era.

As one critic noted in 2010:

“There are songs that are more written by their times than by any individual in that time, a song that the times seem to call for, a song that is just gonna be a perfect strike rolled right down the middle of the lane, and the lane has already been grooved for the strike.”

This song – along with others such as “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” and “Chimes of Freedom” – are among the reasons Bob Dylan received the Nobel Prize in Literature.

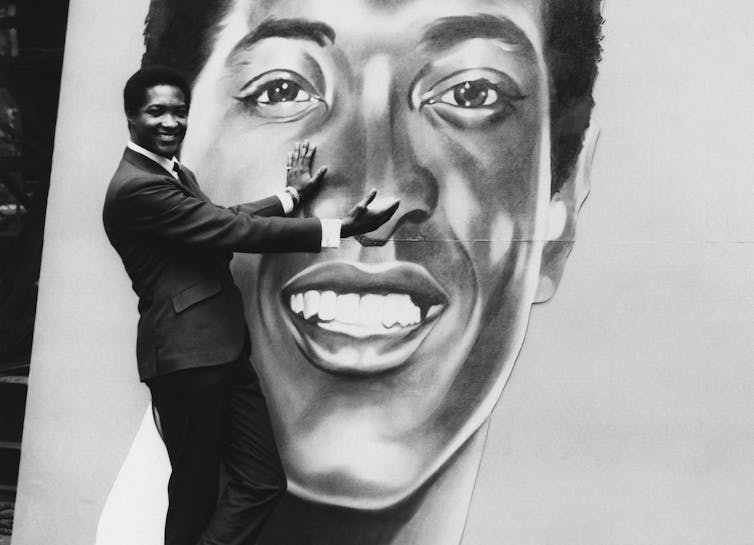

“A Change is Gonna Come,” Sam Cooke, 1964

During a 1963 tour in the South, Cooke and his band were refused lodging at a hotel in Shreveport, Louisiana.

African Americans routinely faced segregation and prejudice in the Jim Crow South, but this particular experience shook Cooke.

So he put pen to paper and tackled a subject that represented a departure for Cooke, a crossover artist who made his name with a series of Top 40 hits.

The lyrics reflect the anguish of being an extraordinary pop headliner who nonetheless needs to go through a side door.

AP Photo

Showcasing Cooke’s gospel roots, it’s a song that painfully and beautifully captures the edge between hope and despair.

“It’s been a long, a long time coming,” he croons. “But I know a change is gonna come.”

Sam Cooke, in composing “A Change is Gonna Come,” was also inspired by Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind”: According to Cooke’s biographer, upon hearing Dylan’s song, Cooke “was almost ashamed to have not written something like that himself.”

“Come See About Me,” The Supremes, 1964

This was one of my favorites of their songs at the time – upbeat, fun and necessarily “unpolitical.”

The Supremes’ record label, Motown, played an important role bridging a cultural divide during the civil rights era by catapulting black musicians to global stardom.

The Supremes were the Motown act with arguably the broadest appeal, and they paved the way for other black artists to enjoy creative success as mainstream acts.

Through their 20 top-10 hits and 17 appearances from 1964 to 1969 on CBS’ popular weekly live program “The Ed Sullivan Show,” the group had a regular presence in the living rooms of black and white families across the country.

“Say it Loud – I’m Black And I’m Proud,” James Brown, 1968

James Brown – the self-proclaimed “hardest working man in show business” – built his reputation as an entertainer par excellence with brilliant dance moves, meticulous staging and a cape routine.

But with “Say it Loud – I’m Black And I’m Proud,” Brown seemed to be consciously delivering a starkly political statement about being black in America.

The track’s straightforward, unadorned lyrics allowed it to quickly become a black pride anthem that promised “we won’t quit movin’ until we get what we deserve.”

“Respect,” Aretha Franklin, 1967

If I could choose only one song to represent the era it would be “Respect.”

It’s a cover of a track previously written and recorded by Otis Redding. But Franklin makes it wholly her own. From the opening lines, the Queen of Soul doesn’t ask for respect; she demands it.

The song became an anthem for the black power and women’s movements.

As Franklin explained in her 1999 autobiography:

“It was the need of a nation, the need of the average man and woman in the street, the businessman, the mother, the fireman, the teacher – everyone wanted respect. It was also one of the battle cries of the civil rights movement. The song took on monumental significance.”

Of course, these five songs can’t possibly do the decade’s music justice.

Some other tracks that I share with my students and count among my favorites include Simon & Garfunkel’s “The Sound of Silence,” Barry McGuire’s “Eve of Destruction” and Lou Rawls’ “Dead End Street.”![]()

Michael V. Drake, President, The Ohio State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.