A Note of Grace in Sugarhill Gang′s Sad, Angry Film

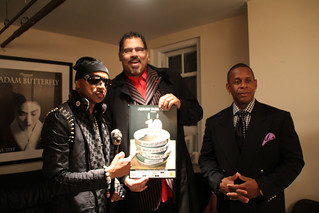

Sugarhill Gang regoups as Rapper's Delight: Hen Dogg, Wonder Mike and Master Gee at the Garden State Film Festival. (Photo by Christine A. Scheller)

It’s been more than 30 years since a trio of young men from Englewood, New Jersey, recorded the first cross-over hip-hop hit, “Rapper’s Delight.” After a drawn-out legal battle with their former record label, Sugar Hill Records, two members of the original Sugarhill Gang, Mike “Wonder Mike” Wright and Guy “Master Gee” O’Brien, have teamed up with Henry “Hen Dogg” Williams in a group named for the Sugarhill Gang’s one big hit. The band’s evolution and protracted legal fight is the subject of a new Roger Paradiso documentary called I Want My Name Back.

The original Sugarhill Gang from back in the day, crica 1979.

I saw the film and a brief Rapper’s Delight performance at the Garden State Film Festival in Asbury Park, New Jersey, March 24. It’s a bitter film about how record label owners Sylvia Robinson, her husband Joe Robinson, and their sons allegedly defrauded the group members financially and then trademarked the name Sugarhill Gang and the stage names “Wonder Mike” and “Master Gee.” After Wright and O’Brien left the record label, the Robinson’s son Joe Jr. actually began performing as “Master Gee” with remaining original member Henry “Big Bank Hank” Franklin.

In the film, O’Brien says the Robinsons didn’t seem like crooks to him at first, in part because Sylvia Robinson was going to Bible studies when they met and “praising the Lord.”

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JhStIg3Ft5s&w=560&h=315]

Williams, who was a former producer at the now defunct Sugar Hill Records, says, “Big Joe was a crook, but he was an honest crook.” He would tell artists “straight up” what he was going to take from them.

O’Brien says he descended into a “deep state of violent depression” and began using drugs after parting ways with the Robinsons over their alleged thievery. He sold magazines door-to-door and says that helped him emerge from the depths. Because his anger isn’t as raw as Wright’s in the film, I thought perhaps faith or a 12-step program had played a role in his recovery. I was wrong.

“I did it myself,” O’Brien told UrbanFaith. “I just walked away from it. It didn’t benefit me. It made me worse, and in the situation, there was enough bad going around so I didn’t want to add to the equation.”

“I believe in the power of positive thinking and self-improvement,” he said. “I trained my brain and I maintained a really positive attitude. I looked at every adversity as a seed to an equal and greater benefit. That just gave me the opportunity to become stronger than whatever it was.”

Rapper's Delight: The hit that made hip-hop mainstream. (Photo by Christine A. Scheller)

Wright struggled with diabetes and asthma after he left the band and the record label, but he also started a successful painting business, got married, had children, and later divorced. He returned to the Sugar Hill label from 1994 to 2005, but says in the film that those years were “the dumbest years of my life.”

Perhaps this explains why the vitriole Wright hurls at Joe Robinson Jr. and Jackson is so aggressive and bitter. He gave the label a second chance and felt like he got burned again. He calls his former bandmate “gutless” and “heartless” in the film for not leaving with him.

But in 2000, when Joe Robinson Sr. was on his deathbed, Wright went to visit him in the hospital. Amidst all the anger and accusations in the film, I was surprised to hear him say he went there to pray with Robinson. I asked him about this after the screening and concert. He said he was able to pray with the man who had done him so much harm because “He [Christ] loved us first before we loved Him, and because He said, ‘God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten son.’ He forgave the people. He said, ‘Father, forgive them because they know not what they do.’ How many times do we forgive somebody? Seven times? No. Seventy times seven. And it’s grace. Grace can’t be earned. It’s mercy. Mercy has to be shown in unruliness.”

Wright then recounted the story of God’s mercy in delivering the Israelites on the banks of the Red Sea and with manna and a pillar of fire despite their complaining.

He said it was the “prayer of salvation” that he prayed with Robinson.

“I was hoping that he made that move because what they did to us was absolutely terrible–it can’t be overlooked, but eternity is eternity. This is for a small season, and it was really wrong, but you have to overlook that when you’re feet are on the edge of going over to the other side. So, I had to throw all that out the window. And, it really wasn’t hard when it came down to that. When it comes down to crossing over, we’re all one heartbeat, we’re all one breath away from eternity,” he said.

Wright is a person of faith, he said, but he doesn’t want to “put walls” around himself or “any kind of bondage” because “there’s freedom in Christ.”

“I want my priorities to be changed,” he said.

A painful journey exposed: Mike "Wonder Mike" Wright expresses it all in film and song. (Photo by Christine A. Scheller)

It was perhaps a necessary qualification because forgiveness, mercy, and an eternal perspective don’t come through in this film at all. But when he was introducing the band’s song, “I Want My Name Back,” during the concert he said the song and the film were “cathartic” for him. Thirty years worth of frustration and anger spill out on screen. Even after Wright and O’Brien reunited, Joe Robinson Jr. allegedly tried to sabotage their careers.

O’Brien told me the film was cathartic for him too, but said he has never seen it in its entirety. “For me, it’s just a little eerie, so I kind of take it in bits and pieces,” he said.

The music Rapper’s Delight performed was “clean” and upbeat. As someone who is far from being a rap aficionado, I thought perhaps I was guilty of stereotyping a genre, but in an interview with NPR Wright said the group’s message “wasn’t too heavy” and that what he “wanted to portray was three guys having fun.” This, music historians say, is why “Rapper’s Delight” was a such a big hit.

“When we strike up [Rapper’s Delight], the audience goes crazy 100 percent of the time,” Wright recently told The New York Times. “That’s love,” he said. “That’s appreciation. I’ll never take it for granted.”

Why is it that we expect perfect consistency from people of faith? While I can’t imagine myself publicly expressing the kind of raw, intensely personal anger that Wright expresses in this film, I’ve certainly felt it and communicated it in private, and I’ve never had my public identity stolen. Who knows what I would say and do if someone did that to me?