American cities from Atlanta to New York City still use buildings, roads, ports and rail lines built by enslaved people.

The fact that centuries-old relics of slavery still support the economy of the United States suggests that reparations for slavery would need to go beyond government payments to the ancestors of enslaved people to account for profit-generating, slave-built infrastructure.

Debates about compensating Black Americans for slavery began soon after the Civil War, in the 1860s, with promises of “40 acres and a mule.” A national conversation about reparations has reignited in recent decades. The definition of reparations varies, but most advocates envision it as a two-part reckoning that acknowledges the role slavery played in building the country and directs resources to the communities impacted by slavery.

Through our geographic and urban planning scholarship, we document the contemporary infrastructure created by enslaved Black workers. Our study of what we call the “landscape of race” shows how the globally dominant economy of the United States traces directly back to slavery.

Looking again at railroads

While difficult to calculate, scholars estimate that much of the physical infrastructure built before 1860 in the American South was built with enslaved labor.

Railways were particularly critical infrastructure. According to “The American South,” an in-depth history of the region, railroads “offered solutions to the geographic barriers that segmented the South,” including swamps, mountains and rivers. For inland planters needing to get goods to port, trains were “the elemental precondition to better times.”

Our archival research on Montgomery, Alabama, shows that enslaved workers built and maintained the Montgomery Eufaula Railroad. This 81-mile-long railroad, begun in 1859, connected Montgomery to the Central Georgia Line, which served both Alabama’s fertile cotton-growing region – cotton picked by enslaved hands – and the textile mills of Georgia.

The Eufala Railroad also gave Alabama commercial access to the Port of Savannah. Savannah was a key cotton and rice trading port, and slavery was integral to the growth of the city.

Today, Savannah’s deep-water port remains one of the busiest container ports in the U.S. Among its top exports: cotton.

The Eufala Railroad closed in the 1970s. But the company that funded its construction – Lehman Durr & Co., a prominent Southern cotton brokerage – existed well into the 20th century.

Examining court affidavits and city records located in the Montgomery city archive, we learned the Montgomery Eufaula Railroad Company received US$1.8 million in loans from Lehman Durr & Co. The main backers of Lehman Durr & Co. went on to found Lehman Brothers bank, one of Wall Street’s largest investment banks until it collapsed in 2008, in the U.S. financial crisis.

Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.

Slave-built railroads also gave rise to Georgia’s largest city, Atlanta. In the 1830s, Atlanta was the terminus of a rail line that extended into the Midwest.

Some of these same rail lines still drive Georgia’s economy. According to a 2013 state report, railways that went through Georgia in 2012 carried over US$198 billion in agricultural products and raw materials needed for U.S. industry and manufacturing.

Rethinking reparations

Savannah, Atlanta and Montgomery all show how, far from being an artifact of history, as some critics of reparations suggest, slavery has a tangible presence in the American economy.

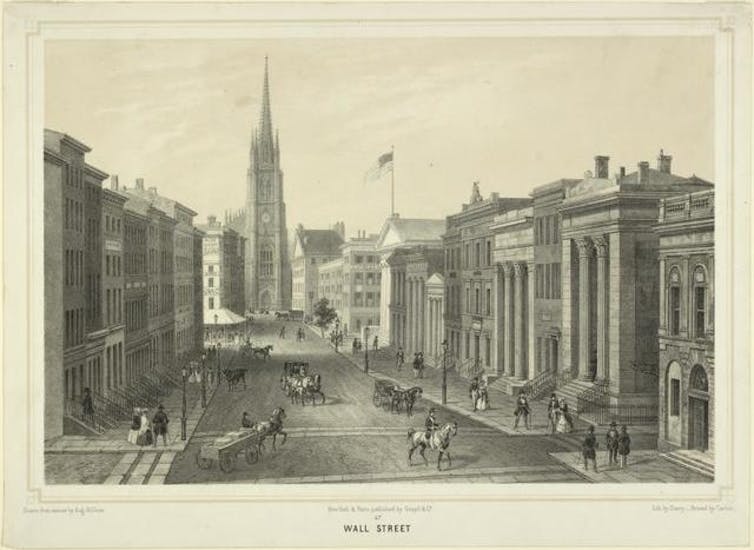

And not just in the South. Wall Street, in New York City, is associated with the trading of stocks. But in the 18th century, enslaved people were bought and sold there. Even after New York closed its slave markets, local businesses sold and shipped cotton grown in the slaveholding South.

Geographic research like ours could inform thinking on monetary reparations by helping to calculate the ongoing financial value of slavery.

Like scholarship drawing the connection between slavery and modern mass incarceration, however, our work also suggests that direct payments to indviduals cannot truly account for the modern legacy of slavery. It points toward a broader concept of reparations that reflects how slavery is built into the American landscape, still generating wealth.

Such reparations might include government investments in aspects of American life where Black people face disparities.

Last year the city council in Asheville, North Carolina, voted for “reparations in the form of community investment.” Priorities could include efforts to increase access to affordable housing and boost minority business ownership. Asheville will also explore strategies to close the racial gap in health care.

It is very difficult, perhaps impossible, to calculate the total contemporary economic impact of slavery. But we see recognizing that enslaved men, women and children built many of the cities, rail lines and ports that fuel the American economy as a necessary part of any such accounting.![]()

Joshua F.J. Inwood, Associate Professor of Geography Senior Research Associate in the Rock Ethics Institute, Penn State and Anna Livia Brand, Assistant Professor, University of California, Berkeley

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.