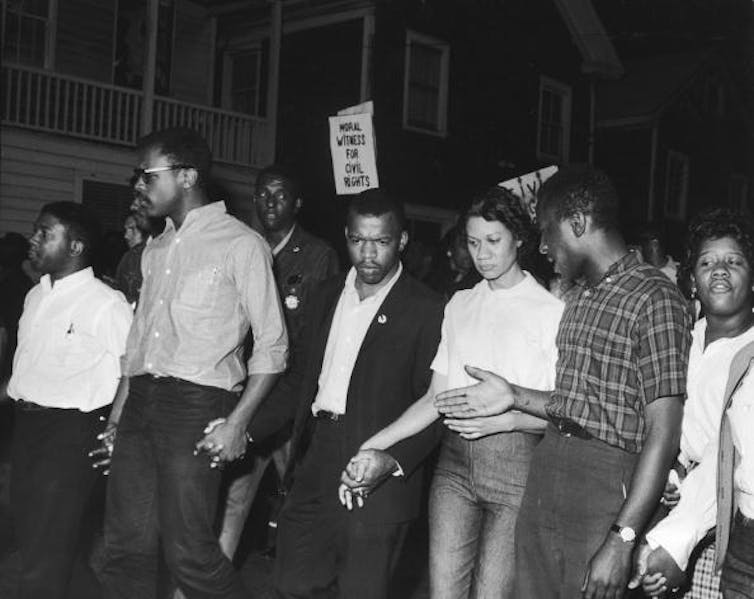

John Lewis, right, marched with Dr. Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to fight for equality. Steve Schapiro / Contributor/GettyImages

As an 18-year-old student attending a training session for activists at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, John Lewis stuttered and struggled to read. A visiting professor mocked his stammered speech and “poor reading skills” and dismissed Lewis’ potential as a “suitable leader” for the burgeoning movement.

Famed activist and organizer Septima Clark rose to his defense and her support of Lewis paid off.

The unassuming teenager from the backwoods of Troy, Alabama, became a giant of the Black freedom struggle and, ultimately, would go on to serve more than three decades in Congress. He died on July 17.

Enthralled by ‘Social Gospel’

Lewis enrolled in American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee, mainly because it charged no tuition, but also due to the profound moral calling that he felt in his life. It was in Nashville where Lewis grew fascinated with the potential of the Social Gospel – a theoretical movement that applied Christian principles to addressing social problems such as poverty and white supremacy.

He soon came under the tutelage of James Lawson, a graduate student at Vanderbilt who was fully immersed in the doctrines of non-violence. Lawson trained other notable activists such as Diane Nash, James Bevel and Bernard Lafayette – all friends and contemporaries of Lewis.

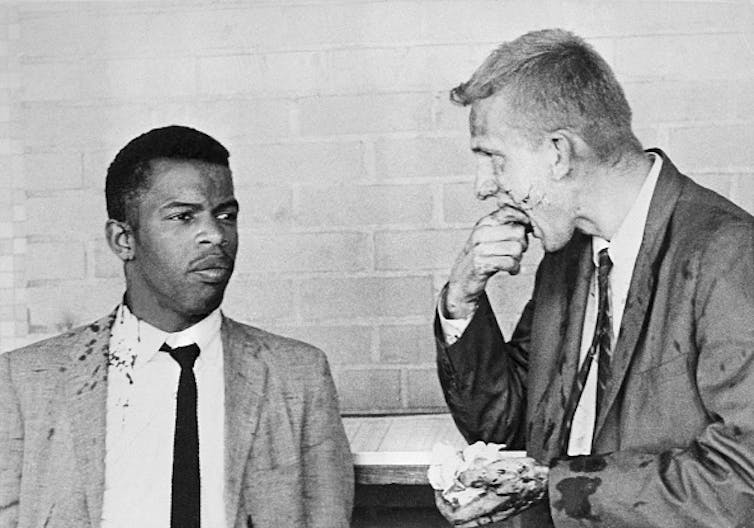

Francis Miller / Contributor/GettyImages

The student activism that emerged from southern Black colleges beginning in February of 1960 was the catalyst that the modern civil rights movement desperately needed to confront segregation. The thrust of direct-action protests, such as sit-ins and Freedom Rides, provided the dramatic confrontation that the earlier bus boycotts did not.

However, it was Lawson’s young pacifist disciples from Nashville that heavily influenced the ideology of the early student movement. It also aided in the creation of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, better known as SNCC.

In dedicating his life to the movement as a young student, Lewis willingly gave up the comforts, experiences and accoutrements of a typical college student. Instead of gaining traditional work experience, Lewis got an insider’s look at numerous southern jails and prisons. His activism led to 40 arrests between 1960 and 1966.

Bettmann / Contributor/GettyImages

Late-night bull sessions with his fellow SNCC activists who debated the proper path towards freedom became his laboratory. Sit-ins and Freedom Rides served as his examinations. They often resulted in beatings and bloodshed.

SNCC leadership

By 1963 Lewis had assumed the chairmanship of SNCC, a position he would hold for the next three years. The formidable organization would undergo its most drastic changes during this period as they wrangled with more moderate and traditional organizations, concerns about white liberalism and the intractable nature of white supremacy.

Lewis and other SNCC organizers were forced to swallow a bitter pill during the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Although Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech became a focal point, it was Lewis’ speech that drew the most controversy.

Archbishop Patrick O’Boyle, along with march organizer Bayard Rustin, forced Lewis to change his original draft that placed a heavy critique on the slow response of the Kennedy administration in protecting the civil and human rights of activists in the Deep South. The edit prompted Malcolm X to derisively refer to the event as “The Farce on Washington.” It was not the last ideological scrum SNCC would have with liberals and moderates.

During the Democratic National Convention in 1964, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, or MFDP, arrived in Atlantic City, New Jersey, expecting to be the duly recognized delegation from the Magnolia State in place of the all-white delegation of the party that had used violence and intimidation in an attempt to keep Blacks from the polls.

Famed activist Fannie Lou Hamer declared that “if the MFDP is not seated now, I question America.” The party was not seated. A backroom compromise – orchestrated between traditional Black moderates such as NAACP head Roy Wilkins, SCLC organizer Bayard Rustin and Dr. King – left many younger activists bitter and broken. “This was the turning point of the civil rights movement,” Lewis declared. “We had played by the rules, done everything we were supposed to do, had played the game exactly as requested, had arrived at the doorstep, and found the door slammed in our face.”

A year after the disappointment of Atlantic City, the learning curve would continue for Lewis.

As bitter as he and other SNCC activists were about the fallout from the 1964 Democratic Convention, Lewis was still a committed ideologue who held fast to his belief in non-violence as a way of life. That position grew increasingly unpopular with younger activists who championed their constitutional right to armed self-defense in the face of tyranny.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.]

Many SNCC activists grew wearisome of the practical politics, moderation and compromise that some (including Lewis) argued produced setbacks within the movement. This frustration was on full display during Lewis’ most famous moment – the Selma to Montgomery March of 1965. SNCC’s executive committee had voted against the organization’s involvement because they saw such protest marches as largely ineffective. Lewis participated anyway. The result was “Bloody Sunday,” a horrific display of white terrorism that served as a springboard for the passage of the Voting Rights Act later that year. The world watched in horror as television cameras captured the moment that Lewis and hundreds of other peaceful protesters were teargassed, beaten and trampled by state troopers.

Like many committed activists, the social and political education of John Lewis had numerous twists and turns – from a wide-eyed and eager disciple of nonviolence (a commitment that never wavered) to a seasoned activist and organizer whose heroics and courage made him an icon of the movement. That journey came with bumps and bruises – both literally and figuratively – and he would later employ some of those lessons as a United States congressman representing the 5th Congressional District of Georgia for 33 years. In this role, Lewis would champion legislation that upheld the ideals that made him an icon of the movement. He sponsored or co-sponsored thousands of bills targeting poverty, gun violence, civil rights, health care and reform of America’s justice system, just to name a few. He became an award-winning author, and he was lionized as “the conscience of Congress.”

While Lewis learned the fine art of negotiating during his years as a movement leader, he never compromised in his insistence for justice and equality for all. In a tweet from 2018, Lewis implored young idealists and activists to “Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble.” Lewis remained a noise maker and a “drum major for peace” until his final days, and his courage and sacrifice should be an inspiration for us all.![]()

Jelani M. Favors, Associate Professor of History, Clayton State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.