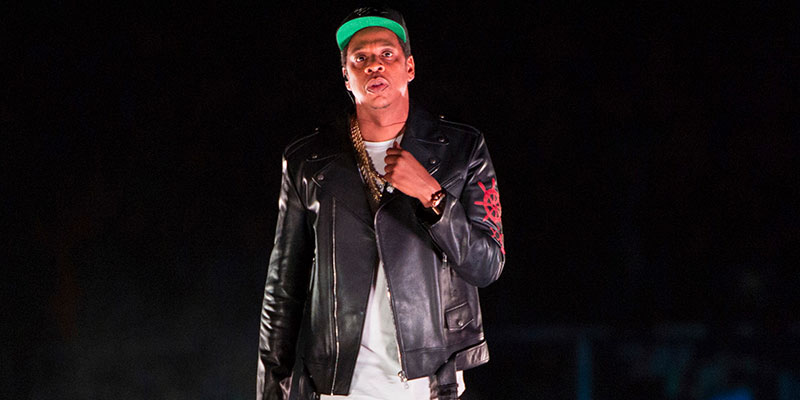

Millionaire rapper Shawn Carter, aka Jay-Z, has proved yet again why he is larger than life. He is embroiled in a contractual dispute over the US$204m (£159m) sale of his clothing brand to Iconix Brand Group a decade ago.

In a twist that has now thrown the world of arbitration into a frenzy, Jay-Z recently won a temporary decision from a New York court to halt the process on the grounds there aren’t enough black arbitrators to settle it fairly within the terms of the contract. If this argument ultimately carries the day, it will require a severe reorganization and opening up of the arbitration profession, one of the most cliquish corners of the legal business – and not just in America, but around the world.

Like many business contracts, the original Jay-Z/Iconix deal agreed that any disputes would be settled by a commercial arbitration process. The contract stipulated that the parties would use arbitrators provided by the American Arbitration Association (AAA).

But as part of a dispute over intellectual property rights, Jay-Z’s lawyers are arguing that the arbitration clause is invalid because they could not “identify a single African-American arbitrator on the ‘Large and Complex Cases’ roster” provided by the association. Even when the AAA went through its expanded list of 200 potential arbitrators, it could only identify three African-Americans – one of whom was ineligible to come on board because they work for the law firm representing Iconix.

Jay-Z’s lawyers argued before the New York Supreme Court that white arbitrators exhibit “unconscious bias” towards black defendants; and that the AAA’s lack of racial diversity consequently “deprives litigants of color of a meaningful opportunity to have their claims heard by a panel of arbitrators reflecting their backgrounds and life experience”. The procedure, they went on, “deprives black litigants … of the equal protection of the laws, equal access to public accommodations, and mislead consumers into believing that they will receive a fair and impartial adjudication”.

The New York Supreme Court’s decision to grant a stay on the back of these arguments is unprecedented and will become legendary within the profession. And unlike traditional courts, where judges are usually only bound to follow decisions within the same jurisdiction, arbitration is essentially one global system. If New York decides that these are the rules, the effects will be felt around the world.

The exclusion problem

What the case has highlighted is that arbitrators in the US, but also in most Western societies, are disproportionately white, male and aged. The same is true of courts, but more is arguably expected from arbitrators as the field of recruitment is wider – with less emphasis on legal training and professional qualifications.

This situation is hardly surprising given that big law firms are the incubation beds for commercial arbitrators. The chances of being appointed by businesses to settle highly complex matters like Jay-Z’s case increase exponentially if the arbitrator works in the so-called golden circle of law firms and this is where the shortage begins.

BCFC

Don’t tell anyone this, but the law firm representing Jay-Z, Quinn Emanuel, itself has a big diversity deficit at partner level, with only three African-American partners listed in a list of almost 300. Even if the firm were allowed to supply black arbitrators to handle Jay-Z’s case itself, it wouldn’t be able to. If black partners are this scarce, you might as well look for black unicorns to fill arbitration panels.

The shortage is just as problematic in complex international arbitrations. In 2013, around a third of the parties to the International Chamber of Commerce Court of Arbitration were from Africa, Asia, and the Pacific. Since then, just 15% of appointees were from those regions. Meanwhile, appointments of African arbitrators at the Permanent Court of Arbitration and black judges at the World Court are proportionately very low.

There are few renowned non-white arbitrators in international petroleum negotiation – despite the fact that nearly 60% of petroleum is produced outside Europe and North America. There are even fewer developing-world experts in international boundary disputes. Arguably developing countries are constantly shortchanged in international justice as a result.

What to do

How do we address these issues? We could throw the burden back on the likes of Jay-Z by saying he should have fought for diversity in arbitrators at the drafting stage of his sales contract. That may well be what the court ultimately does in his case, but what then?

It is generally accepted that contractual specifications about arbitration cannot violate national laws. These would include race discrimination laws, though the limits of this were shown in a relatively recent UK judgment, Jivraj v Hashwani (2011). Here, the contract stipulated that arbitrators had to be respected Muslim members of the Ismaili community. When challenged as racial discrimination, the Supreme Court decided that the relevant UK laws only applied to employees and not to arbitrators because they were not employees.

But if that left the likes of Jay-Z free to push for African-American arbitrators as part of business contracts, there is still the problem of a general dearth of them. If he does ultimately lose his case in New York, it will still have highlighted this gap in the market. Perhaps in future, black dealmakers will insist on any arbitration taking place somewhere with more black arbitrators.

The bottom line is that we need recruitment programmes to encourage black arbitrators now and to recognize that those in place should be more frequently offered for appointments so that they are experienced enough to handle large complex cases. And to fix the current shortage, we also have to address the diversity issues in the legal profession as a whole.

Too often at present, we’re kidding ourselves. The American Arbitration Association has a program to mentor diverse young arbitrators and promises lists of arbitrators of at least 20% diversity, for example. But it is only able to offer this proportion by lumping together all diversity including gender, age, and ethnic background – and 20% is hardly a great achievement anyway. If demand for more black representation rises and centers for arbitration like New York and London don’t offer enough people, new rivals may well step up to the plate.![]()

Gbenga Oduntan, Reader (Associate Professor) in International Commercial Law, University of Kent

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.