After struggling over wording in the prayer, one ecumenical organization is developing new tools to address divides within its own network.

(RNS) — In October, Christian Churches Together, an ecumenical group of Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox Christians, gathered for its annual forum to address a topic that has plagued the church and society beyond it: polarization.

They sought to answer the question “Who Does Jesus Call Our Christian Churches to Be in a Polarized Society?” But they found that polarization within their own ranks made it hard to move forward with a response. Two months later, on Dec. 9, they released a prayer.

“In the power of the Holy Spirit that blows where it will, remove the divisions and historical inequities between Christians and in society — between those who strive to follow you and between us who raise this prayer,” it reads. “Show us new ways to be your churches in these troubled, polarized times. Give us fresh vision to respond in love to a world consumed by hate and fear.”

Christian Churches Together logo. Courtesy image

Reaching prayerful words that might seem to outsiders to be relatively innocuous required some heated discussion.

“We did have challenging moments in that conversation about the prayer, I think because prayer is such a central part of our common tradition, Christian tradition, that there were strong feelings around how we should pray and how we should end the prayer,” said Monica Schaap Pierce, CCT’s executive director.

“And so when that kind of came to a head, we decided to have a cover letter to explain the diversity of approaches to prayer.”

The letter, addressed to its participating churches, gave three options for ending the prayer: “Ashe,” a closing used by some historic Black churches that is rooted in many African contexts; “in the name of the Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit,” used in Catholic and Orthodox settings; or another ending chosen by the person saying the prayer.

Since the meeting, after struggling over wording in the prayer, the organization has taken steps to develop new tools to address divides within its own network.

Monica Schaap Pierce. Photo courtesy of CCT

Schaap Pierce, a former CCT steering committee member who served for four years as the ecumenical officer of the Reformed Church in America, said letters and other statements — on racism, poverty and immigration reform — have been produced by the ecumenical organization since its founding two decades ago. But they often take time and debate.

“There is a lot of conversation that leads up to the decision and it often is a bit heated and challenging, but we do come to consensus,” a decision-making mode she says “can honor all the voices in the room,” with many perspectives across generations, denominations and socioeconomic and racial backgrounds.

The organization, founded in 2001, includes 34 communions and Christian organizations that Schaap Pierce says represent 57 million American Christians. It includes five “families”: Catholic, Orthodox, historic Black Protestant, mainline Protestant and evangelical/Pentecostal.

She said the organization is seeking to address polarization within and among those Christian subgroups even as it hopes to eventually extend what it learns to broader communities. At its October forum in Indianapolis, following a process used by the World Council of Churches, several dozen people raised orange or blue cards as they sought to gather consensus, with the colors showing they were “warm” or “cool” to an idea being discussed.

Some of the attendees responded to an invitation to foster understanding among themselves in a new way a month later.

In November, dozens of CCT participant group members and observers devoted four and a half hours over two days to a workshop conducted by Resetting the Table, a nonprofit that teaches listening exercises designed to reduce polarization.

Resetting The Table logo. Courtesy image

“The million-dollar question is how can we shift ourselves and others from the usual rigidity of how we listen across differences and how we listen in general,” facilitator Eyal Rabinovitch said at the start of the second online session after a get-to-know you gathering two days earlier.

“Can we support people to move beyond their confirmation bias so that they can actually take in information, take in views and people that they might otherwise dismiss out of hand?”

In one instance, two men who had different responses to a hypothetical statement about voting — “We should automatically register all eligible citizens to vote” — spent time in a Zoom small group coming to understand the side each was on.

Anthony Elenbaas, a member of the Christian Reformed Church in North America, was all-in, seeing the increasing barriers to voting across the U.S. as “antithetical to the founding principles of the country.”

Dana Wiser, a participant from an Anabaptist background, opposed the statement, recalling how his father was interred in work camps for his conscientious objection to the draft during World War II.

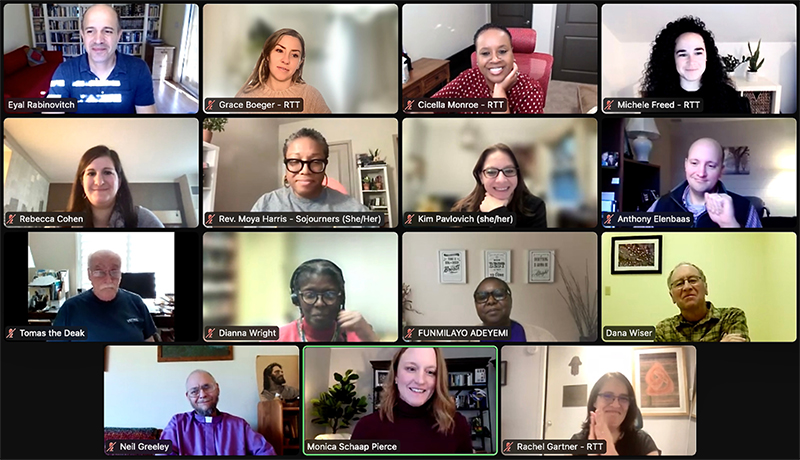

Christian Churches Together participant group members attend a workshop conducted by Resetting The Table in November 2022. Screen grab courtesy of RTT

They achieved what Rabinovitch called “getting to bull’s-eye” — or gaining an understanding of each other’s views — by stating not just what each said to the other but what they were communicating — which could be different.

Wiser told the overall group afterward that though he and Elenbaas started out on opposite extremes of the discussion question they found similarities in their overall views and “also discovered nuances of our positions that we would have completely missed if we had rushed to judgment.”

Added Elenbaas in a later discussion: “It kind of sharpens both your ability to speak but also to hear.”

Religion scholar J. Gordon Melton, who recently retired from Baylor University, was not surprised to hear of the challenges CCT has faced in determining what its representatives could agree to say jointly.

“All Christians want to fellowship with as broad a body as they can but their lines in the sand are drawn on different issues, so as long as you don’t talk about the issue I draw my line in the sand on, we’re great,” he said in an interview. “For different groups the issue that breaks the agreement is different. And ecumenical groups have to learn to do that.”

The Christian Churches Together annual forum was held in Indianapolis in October 2022. Photo courtesy of CCT

Schaap Pierce said the workshop gave her and CCT’s other leaders effective means to continue their consensus methods “in ways that are maybe not as heated and emotionally charged as they have been in the past” even as they consider using the lessons gained in personal as well as professional circles.

“Our faith leaders within CCT who were at the workshop talked about bringing these tools back to their own denominations to share either at the denominational staff level or with a church board,” she said. “Or just even with their family members in order to better understand one another. And to really seek a unity that goes beyond uniformity.”