Jonathan Ebel, CC BY

World War I does not occupy the same space in America’s cultural memory as the American Revolution, the Civil War, World War II or the Vietnam War. The men and women who fought “the Great War” would likely be shocked at this relegation. For them, “the war to end all wars” was the most consequential war ever fought: a struggle between good and evil.

As an author of two books, “Faith in the Fight” and “G.I. Messiahs,” I have spent a good part of the last 15 years thinking about the place of religion in America’s experience of the Great War.

From the beginning of American involvement in the war to the construction of cemeteries in Europe for America’s war dead, Christian imagery framed and simplified a complex, violent world and encouraged soldiers and their loved ones to think of the war as a sacred endeavor.

America as a Christian nation

Writings by and for American soldiers used religious imagery and language, to contrast “progressive,” Christian America and “barbaric,” anti-Christian Germany.

Library of Congress, Serial and Government Publications Division

The June 14, 1918 issue of Stars and Stripes, a weekly newspaper written by and for American soldiers in France, featured an editorial cartoon that drew this stark division. In it, the crown prince of Germany and the Kaiser stroll casually past Christ as he hangs on the cross.

The prince, dressed in black with a skull and crossbones on his hat, smiles at his father and says,

“Oh, look, Papa! Another of those allies!”

The cartoon affirms that America’s cause is Christ’s cause at the same time that it argues that Germans are so morally perverse that they would recrucify Jesus if given the chance.

American pilot Kenneth MacLeish was just as blunt in a letter to his parents. (His mother collected his wartime correspondence and published a memorial collection after his death in combat.) He defended his decision to go to war with a very different image of Jesus, but conveyed a similar lesson about the German foe. He wrote,

“Do you think for a minute that if Christ had been alone on the Mount with Mary, and a desperate man had entered with criminal intent, He would have turned away when a crime against Mary was perpetrated? Never! He would have fought with all the God-given strength He had!”

MacLeish left no room for doubt as to which side should be imagined as Mary’s rapist, and which should be seen as her Christ-like defender. He was equally clear that waging war was morally acceptable. Writing in the same letter, he stated,

“Religion embraces the sword as well as the dove of peace.”

The Christian imagery that filled the pages of Stars and Stripes and the letters and diaries of American soldiers erased Germany’s Christian history and made a religiously diverse and conflicted America into a virtuous, Christian nation.

In fact, Germany, like the U.S., had large numbers of Protestants, Catholics and Jews, and had given rise to many religious movements and denominations that were thriving on American soil. Yet in the eyes of many American soldiers, the war confirmed that Germany was profoundly vicious.

In a letter home, Charles Biddle, another American pilot, reacted angrily to an aerial attack on a field hospital. In response, he cited a French postcard that inverted Jesus’ words from the Gospel of Luke: “Do not forgive them, for they know what they do!”

Christian imagery for the war dead

Library of Congress, Serial and Government Publications Division

World War I came to an end on Nov. 11, 1918. American losses were small by comparison to other combatant nations, but still exceeded 100,000, including 53,000 who were killed in combat. (A large percentage of the other 57,000 died as a result of the global influenza pandemic.) By contrast, France lost 1.2 million soldiers, Great Britain lost 959,000, and Germany lost over two million. As individual American soldiers and the nation thought about how best to memorialize the fallen, they turned again to Christian imagery.

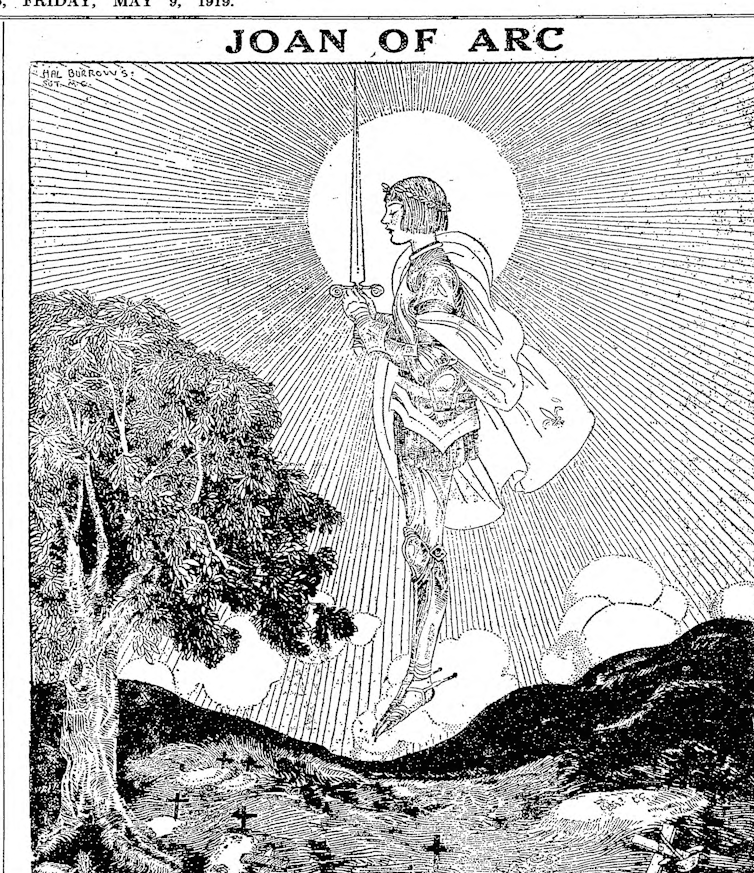

In May of 1919, Stars and Stripes published an image of Joan of Arc and an accompanying poem. Saint Joan hovers over a temporary burial ground, keeping watch over graves marked by crosses. Sergeant Hal Burrows of the Marine Corps signed the drawing. Second Lieutenant John Palmer Cumming wrote the poem.

“The kiss the wind may bear will stir the tranquil leaf.

And lay it softly on the mounds we made.

And we shall labor in the mart or bind the sheaf.

The while her spirit guards their quiet glade.”

The poem and the image confirmed that America’s war dead would not be alone. They would have a saint to watch over them. In dying for the nation, they had proven themselves worthy of such attention.

When the United States government set to work designing and constructing cemeteries in France, England and Belgium, they created environments that look very much like the “quiet glade” picture above, though on a much grander scale: The largest American cemetery, Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery near the French town of Romagne, contains 14,246 graves.

White marble crosses dominate these cemeteries, creating a much more explicitly Christian space than the veterans’ cemeteries located in the United States, where headstones are small, rounded rectangles.

Remembering the diversity

The crosses at Meuse-Argonne and America’s other overseas cemeteries do not call American soldiers to fight, as the Stars and Stripes imagery did. They call Americans to remember. But the crosses work in ways similar to the Stars and Stripes images.

As my research has shown, American men and women who died in the course of World War I came from many walks of life. They differed in terms of religious identity, ethnicity, race and class. Some were brave and morally upright. Others, likely, were not.

America’s Great War cemeteries make this diversity difficult, if not impossible, to discern. The cemeteries that the United States built overseas after World War II use even more pervasive Christian imagery, leaving no room for non-Christian soldiers among the unknowns.

As the crosses rise ramrod straight from tightly manicured lawns, they project American virtue and America’s alignment with Christ. They admit little, if any, moral complexity. The crosses bear the names of the individuals who lie beneath them, but that individuality and the complexities that went along with it are subsumed by a collective identity defined by near uniform Christianity and by nearness to Christ.

The truth is, World War I was not a war of religion. Men from different religious backgrounds fought alongside each other and killed men with whom they may have, in another circumstances, shared a Christian hymn. But in the United States, and in Europe as well, Christianity shaped the experience of the war and memories of it.

As Americans look back across the hundred years since the nation entered the war and try to remember and honor those who fought, they would do well both to note the role of Christian imagery in creating a world of violence and to reach for the diverse voices and experiences that those images all too often obscure.![]()

Jonathan Ebel, Associate Professor of Religion, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.