Buying items that are fair trade, organic, locally made or cruelty-free are some of the ways in which consumers today seek to align their economic habits with their spiritual and ethical views. For 18th-century Quakers, it led them to abstain from sugar and other goods produced by enslaved people.

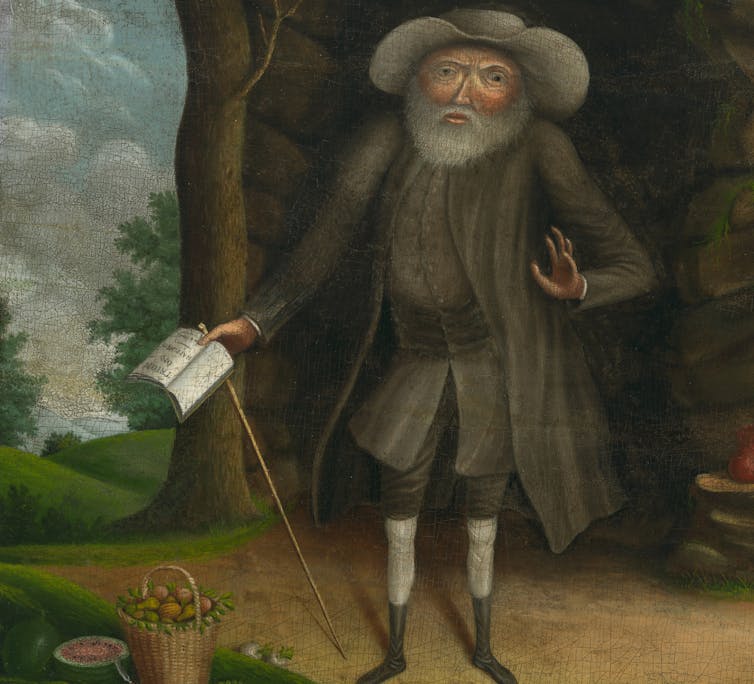

Quaker Benjamin Lay, a former sailor who had settled in Philadelphia in 1731 after living in the British sugar colony of Barbados, is known to have smashed his wife’s china in 1742 during the annual gathering of Quakers in the city. Although Lay’s actions were described by one newspaper as a “publick Testimony against the Vanity of Tea-drinking,” Lay also protested the consumption of slave-grown sugar, which was produced under horrific conditions in sugar colonies like Barbados.

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, only a few Quakers protested African slavery. Indeed, individual Quakers who did protest, like Lay, were often disowned for their actions because their activism disrupted the unity of the Quaker community. Beginning in the 1750s, Quakers’ support for slavery and the products of slave labor started to erode, as reformers like Quaker John Woolman urged their co-religionists in the North American Colonies and England to bring about change.

In the 1780s, British and American Quakers launched an extensive and unprecedented propaganda campaign against slavery and slave-labor products. Their goal of creating a broad nondenominational antislavery movement culminated in a boycott of slave-grown sugar in 1791 supported by nearly a half-million Britons.

How did the movement against slave-grown sugar go from the actions of a few to a protest of the masses? As a scholar of Quakers and the antislavery movement, I argue in my book “Moral Commerce: Quakers and the Transatlantic Boycott of the Slave Labor Economy” that the boycott of slave-grown sugar originated in the actions of ordinary Quakers seeking to draw closer to God by aligning their Christian principles with their economic practices.

The golden rule

Quakerism originated in the political turmoil of the English civil war and the disruption of monarchical rule in the mid-17th century. In the 1640s, George Fox, the son of a weaver, began an extended period of spiritual wandering, which led him to conclude the answers he sought came not from church teaching or the Scriptures but rather from his direct experience of God.

In his travels, Fox encountered others who also sought a more direct experience of God. With the support of Margaret Fell, the wife of a wealthy and prominent judge, Fox organized his followers into the Society of Friends in 1652. Quaker itinerant ministers embarked on an ambitious program of mission work traveling throughout England, the North American Colonies and the Caribbean.

The restoration of the British monarchy in 1660 and the passage of the Quaker Act in 1662 brought religious persecution, physical punishment and imprisonment but did not dampen the religious enthusiasm of Quakers like Fox and Fell.

Quakers believe that God speaks to individuals personally and directly through the “inward light” – that the light of Christ exists within all individuals, even those who have not been exposed to Christianity. As Quaker historian and theologian Ben Pink Dandelion notes, “This intimacy with Christ, this relationship of direct revelation, is alone foundational and definitional of [Quakerism]. … Quakerism has had its identity constructed around this experience and insight.”

This experience of intimacy with Christ led Friends to develop distinct spiritual beliefs and practices, such as an emphasis on the golden rule – “Whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them” – as a fundamental guiding principle.

Quakers were to avoid violence and war-making and to reject social customs that reinforced superficial distinctions of social class. Quakers were to adopt “plain dress, plain speech and plain living” and to tell the truth at all times. These beliefs and practices allow Quakers to emphasize the experience of God and to reject the temptations of worldly pleasures.

Stolen goods

In slave traders’ and slave holders’ minds, racial inferiority justified the enslavement of Africans. By the 18th century, the slave trade and the use of slave labor were integral parts of the global economy.

Many Quakers owned slaves and participated in the slave trade. For them, the slave trade and slavery were simply standard business practice: “God-fearing men going about their godless business,” as historian James Walvin observed.

Still, Quakers were far from united in their views about slavery. Beginning in the late 17th century, individual Quakers began to question the practice. Under slavery, Africans were captured, forced to work and subjected to violent punishment, even death, all contrary to Quakers’ belief in the golden rule and nonviolence.

Individual Quakers began to speak out, often linking the enslavement of Africans to the consumption of consumer goods.

John Hepburn, a Quaker from Middletown, New Jersey, was one of the first Quakers to protest against slavery. In 1714, he published “The American Defence of the Christian Golden Rule,” which cataloged, as no other Quaker had done, the evils of slavery.

Although the publication of Hepburn’s book coincided with statements issued by the London Yearly Meeting, the primary Quaker body in this period, warning of the effects of luxury goods on Quakers’ relationship with God, “The American Defence” did not result in any significant outcry among Quakers against slavery.

Quaker Benjamin Lay also published his thoughts about slavery. He also refused to dine with slaveholders, to be served by slaves or to eat sugar. Lay also dressed in coarse clothes. When smashing his wife’s dishware, he claimed that fine clothes and china were luxury goods that separated Quakers from God. Lay’s actions proved too much for Philadelphia Quakers, who disowned him in the late 1730s.

Quaker antislavery and sugar

Like Lay, Woolman too was shocked when he saw the conditions of enslaved people. For Woolman, the slave trade, the enslavement of Africans and the use of the products of their labor, such as sugar, were the most visible signs of the growth of an oppressive, global economy driven by greed, an evil that threatened the spiritual welfare of all. Consumed most often in tea, sugar symbolized for Woolman the corrupting influence of consumer goods. Soon after his travels through the South, Woolman, who was a merchant, stopped selling and consuming sugar and sugar products such as rum and molasses.

[Explore the intersection of faith, politics, arts and culture. Sign up for This Week in Religion.]

The sweetness of sugar hid the violence of its production. Caribbean sugar plantations were infamous for their high rate of mortality and deficiencies in diet, shelter and clothing. The working conditions were brutal, and tropical disease contributed to a death toll that was 50% higher on sugar plantations than on coffee plantations.

Until his death in 1772, Woolman worked within the structure of the Society of Friends, urging Quakers to abstain from slave-grown sugar and other slave-labor products. In his writings, Woolman envisioned a just and simple economy that benefited everyone, freeing men and women to “walk in that pure light in which all their works are wrought in God.” If Quakers allowed their spiritual beliefs to guide their economic habits, Woolman believed, the “true harmony of life” could be restored to all.

Eighteenth-century Quakers’ attempts to align religious beliefs and economic habits continued into the 19th century. Woolman, in particular, influenced many who believed it possible to create a moral economy. His journal, published in 1774, is an important text about religiously informed consumer habits.

In the 1790s and again in the 1820s, British consumers, Quaker and non-Quaker alike, organized popular boycotts of slave-grown sugar. Although the boycott of sugar and other products of slave labor did not bring about the abolition of slavery on its own, the boycott did raise awareness of the connections between an individual’s relationship with God and the choices they made in the marketplace.

This article is part of a series examining sugar’s effects on human health and culture. Click here to read the articles on TheConversation.com.![]()

Julie L. Holcomb, Associate Professor of Museum Studies, Baylor University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.