The Rev. Ginger Gaines-Cirelli, center, gives the benediction at Foundry United Methodist Church in Washington, D.C., on July 27, 2014. The Rev. Theresa S. Thames, associate pastor, left, and the Rev. Dawn M. Hand, executive pastor, right, joined her. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

The share of women in the ranks of American clergy has doubled — and sometimes tripled — in some denominations over the last two decades, a new report shows.

“I was really surprised in a way, at how much progress there’s been in 20 years,” said the report’s author, Eileen Campbell-Reed, an associate professor at Central Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tenn. “There’s kind of a circulating idea that, oh well, women in ministry has kind of plateaued and there really hasn’t been lot of growth. And that’s just not true.”

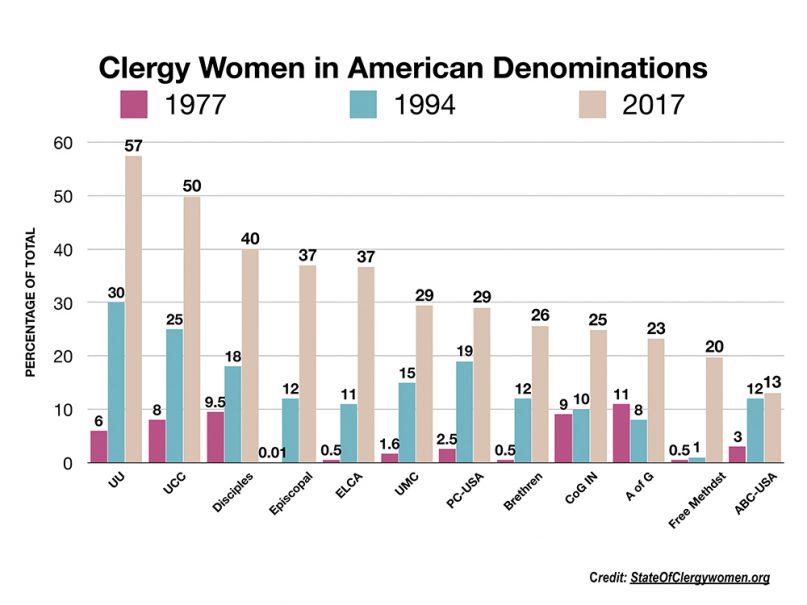

The two traditions with the highest percentages of women clergy were the Unitarian Universalist Association and the United Church of Christ, according to the “State of Clergywomen in the U.S.,” released earlier this month. Fifty-seven percent of UUA clergy were women in 2017, while half of clergy in the UCC were female in 2015. In 1994, women constituted 30 percent of UUA clergy and 25 percent of UCC clergy.

Clergy Women in American Denominations. Graphic courtesy of StateofClergywomen.org

UUA President Susan Frederick-Gray credits the increase to a decision by her denomination’s General Assembly in 1970 to call for more women to serve in ministry and policymaking roles. She noted that as of this year, 60 percent of UUA clergy are women.

“All that work in the ’70s and ’80s made it possible for me, in the early 2000s, to come into ministry and be successful and lead thriving churches,” said Frederick-Gray, “and now be elected as the first female, first woman minister elected to the UUA presidency.”

Campbell-Reed and a research assistant gathered clergywomen statistics that had not been collected across 15 denominations for two decades.

The Rev. Barbara Brown Zikmund, who co-authored the 1998 book “Clergy Women: An Uphill Calling,” welcomed the new report as a way to start closing the gap in the research.

“While the experiences of women and the evolution of church life and leadership have changed dramatically over the past two decades, there have been no comprehensive studies on women and church leadership,” she said.

Reached between recent convocation events at Andover Newton Seminary, the Rev. Davida Foy Crabtree, a retired UCC minister, said the report’s findings were reflected around her.

“I was sort of looking around and seeing so many women and remembering that in my years in seminary in the ’60s how few of us there were,” said Crabtree, a trustee and alumna of the theological school. “So it’s definitely a sea change in terms of women’s ordination.”

Campbell-Reed’s research found a tripling of percentages of clergywomen in the Assemblies of God, the Episcopal Church and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America between 1994 and 2017

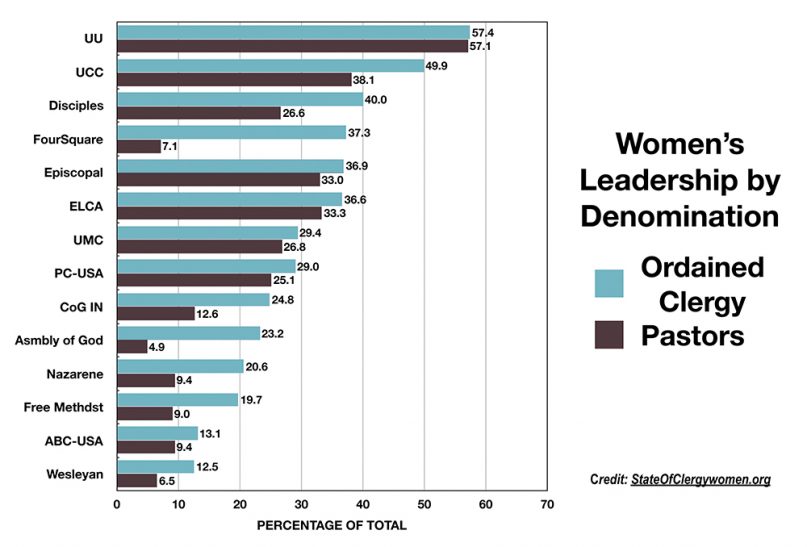

But Campbell-Reed also found that clergywomen — with the exception of Unitarian Universalists — continue to lag behind clergymen in leading their churches. In the UCC, for example, female and male clergy are equal in number, but only 38 percent of UCC pastors are women.

Instead, many clergywomen — as well as clergymen — serve in ministerial roles other than that of pastor, including chaplains, nonprofit staffers and professors.

Paula Nesbitt, president of the Association for the Sociology of Religion, said other researchers have long observed “the persistent clergy gender gap in attainment and compensation.”

For women of color, especially, significant gaps remain, and for women in some conservative churches, ordination is not an option.

Campbell-Reed noted that clergywomen of color “remain a distinct minority” in most mainline denominations. Those who have risen to leadership in the top echelons of their religious groups, she said, have done so after long years of service.

“Some of them are also being recognized for their contributions and their work, like any other person who’s got longevity and wisdom, by being elected as bishops in their various communions,” she said of denominations such as the United Methodist Church and the ELCA.

Women’s Leadership by Denomination. Graphic courtesy of StateofClergywomen.org

Campbell-Reed also pointed out the role of women who serve churches despite being barred from pastoral positions in congregations of the country’s two largest denominations, the Southern Baptist Convention and the Roman Catholic Church.

Former Southern Baptist women like herself have joined the pastoral staffs of breakaway groups such as the Alliance of Baptists, which have women pastoring 40 percent of their congregations. And Catholic women constitute 80 percent of lay ecclesial ministers, who “are running the church on a day-to-day basis,” she said.

Patricia Mei Yin Chang, another co-author of “Clergy Women: An Uphill Calling,” said the new statistics prompt questions about the meaning behind them, such as changing attitudes of congregations or decreases in male clergy.

“Those are two really different causes and they may differ across denominations,” she said.

Campbell-Reed, whose 20-page report concludes with two pages of questions for seminaries, churches, researchers and theologians, said she thinks the answers about the often-difficult job hunt for clergywomen relate to sexism.

“Just because more women enter into jobs in the church or are ordained does not mean that the problems of sexism have gone away,” she said. “At times, the bias is more implicit but no less real.”

But some women are reaching “tall-steeple” pulpits — leadership in prominent churches — instead of being relegated to struggling congregations, often in denominations on the decline.

Frederick-Gray said her denomination, which she said is working on race equality as well as gender equality, is seeing greater opportunities for women to preach in its largest churches. Of the 41 largest congregations in the Unitarian Universalist Association, 20 are served by women senior ministers.

Women’s leadership, Frederick-Gray said, is necessary at a time of decline for many religions.

“The decline is not the responsibility of women,” she said. “But maybe we will be the hope for the future.”

Women have been clergy for centuries in many countries, including the United States.

Without female clergy in many areas, the Christian faith would no longer exist.

Many countries persecute Christians and male leadership is frequently targeted for removal

through arrest, imprisonment, exile and execution. Christian females often continue the work of the gospel, including preaching, visitation of the sick and elderly, discipling new converts and

Christian education for congregations. Many of these churches must meet in secret, and face

constant harassment from both neighbors and governments.

Among African-Americans, we depended upon the female clergy in our slave communities

and free populations of color, especially when males had been targeted for harassment and

had been caught and killed by hostile racists in towns, villages and cities. It is good to see how

many of our churches now have dedicated female pastors who have been able to get seminary

education and advanced degrees in theological fields, including doctorates.

Female clergy tend to be very hard-working and sensitive to the needs of their struggling

parishioners. A few years ago, I had the privilege of meeting a Black South African Presbyterian

pastor whose congregation, she informed us, was composed primarily of AIDS victims and

their families. Black female clergy often do the hard pastoral work in many contexts–the

urban “storefront,” the rural or village church, the congregation experiencing the gradual

transformation/transition of its surrounding neighborhood, etc.

We are grateful to God for all the female clergy worldwide, and in our nation, who answer

God’s call to shepherd people and provide Christian care and support in their communities.