Films Bring Jesus to Cinema in a Powerful Way

Courtesy 20th Century Fox.

Church isn’t the only place people go to learn about Jesus.

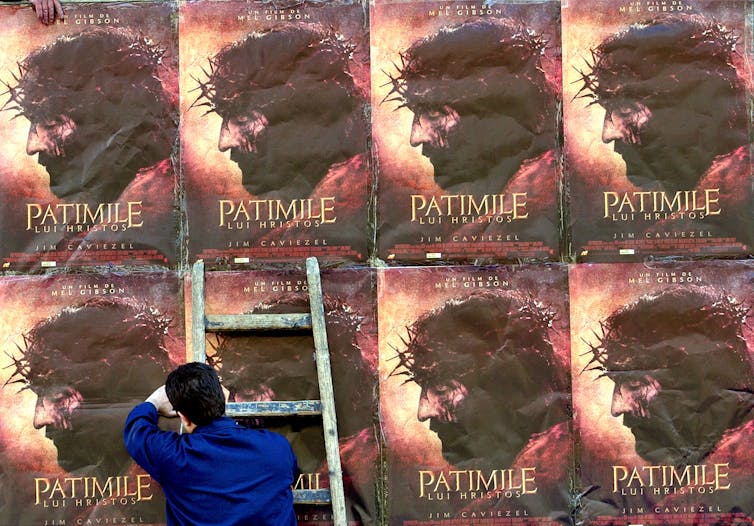

At the beginning of Lent, 15 years ago, devout evangelical Christians did not go to church to have ashes marked on their foreheads. Rather, they thronged to theaters to watch a decidedly Catholic film to begin the Lenten season.

That film was Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ,” which would go on to gross over US$600 million globally. It brought to screen a vivid portrayal of the last few hours of the life of Jesus and even today many can readily recall the brutality of those depictions. The film also stirred up a number of cultural clashes and raised questions about Christian anti-Semitism and what seemed to be a glorification of violence.

This wasn’t the only film to bring Jesus to cinema in such a powerful way. There have, in fact, been hundreds of films about Jesus produced around the world for over 100 years.

These films have prompted devotion and missionary outreach, just as they have challenged viewers’ assumptions of who the figure of Jesus really was.

From still images to moving images

For the last two decades, I have researched the portrayal of religious figures on screen. I have also looked at the ways in which audiences make their own spiritual meanings through the images of film.

Images of Jesus, or the Virgin Mary, have long been part of the Christian tradition. From amulets to icons, paintings to sculptures, Christianity incorporates a rich visual history, so perhaps it is not surprising that cinema has become a vital medium to display the life of Jesus.

Inventors of cinematic technologies, such as Thomas Edison and the Lumière brothers, were among the first to bring Jesus’s life to the big screen at the end of the 19th century. Hollywood continued to cash in on Christian audiences all through the 20th century.

In 1912, Sidney Olcott’s “From the Manger to the Cross” became the first feature length film to offer a full account of the life of Christ.

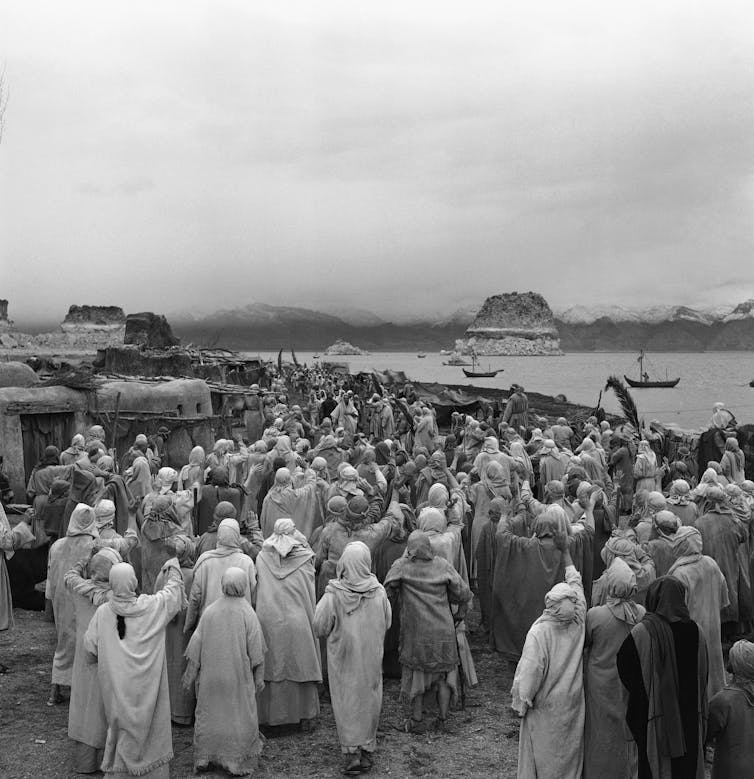

Fifteen years later, crowds flocked to see Cecil B. DeMille’s “The King of Kings”, demonstrating the power of a big budget and a well-known director. Writing about DeMille’s film some years later, film historian Charles Musser commented how the film evoked “Christ’s charisma” through “a mesmerizing repertoire of special effects, lighting and editing.”

In Hollywood’s portrayal, Jesus was a white, European man. In Nicholas Ray’s 1961 film, “King of Kings” Jeffrey Hunter made a deep impression on his audience in the role of Jesus with his piercing blue eyes. Four years later, George Stevens’s “The Greatest Story Ever Told”, cast the white Swedish actor Max von Sydow in the lead role.

AP Photo

In all these films, evidence of Jesus’s Jewish identity was toned down. Social or political messages found in the gospels – such as the political charge of a “kingdom of God” – were smoothed over. Jesus was portrayed as a spiritual savior figure while avoiding many of the socio-political controversies.

This was, as Biblical studies scholar Adele Reinhartz put it, not Jesus of Nazareth, but the creation of a “Jesus of Hollywood.”

Global moral instruction

Many of these films were useful for Christian missionary work.

An advertisement for Olcott’s film, for example, stated how it was “destined to be more far-reaching than the Bible in telling the story of the Savior.” Indeed, as media scholars Terry Lindvall and Andrew Quicke have noted, many Christian leaders throughout the 20th century utilized the power of film for moral instruction and conversion.

A 1979 film, known as “The Jesus Film”, went on to become the most watched film in history. The film was a relatively straightforward depiction of the life of Jesus, taken mainly from the gospel of Luke.

The film was translated into 1,500 languages and shown in cities and remote villages around the world.

The global Jesus

But, as majority Christian population shifted from Europe and North America to Sub-Saharan Africa, South America, and South Asia, so did portrayals of Jesus: they came to reflect local cultures and ethnicities.

In the 2006 South African film “Son of Man”, for example, Jesus, his mother and disciples are all black, and the setting is a contemporary, though fictionalized, South Africa. The film employed traditional art forms of dance and music that retold the Jesus story in ways that would appeal to a South African audience.

It was the same with a Telugu film, “Karunamayudu” (Ocean of Mercy), released in 1978. The style resembles a long tradition of Hindu devotional and mythological films and Jesus could easily be seen as part of the pantheon of Hindu deities.

For the past four decades in southern India and beyond, villagers have gathered in front of makeshift outdoor theaters to watch this film. With over 100 million viewers, it has become a tool for Christian evangelism.

Other films have responded to and reflected local conditions in Latin America. The Cuban film “The Last Supper,” from 1976, offered a vision of a Jesus that is on the side of the enslaved and oppressed, mirroring Latin American movements in Liberation Theology. Growing out of the Cold War, and led by radical Latin American priests, Liberation Theology worked in local communities to promote socio-economic justice.

Meanwhile, the appeal of some of these films can also be gauged from how they continue to be watched year after year. The 1986 Mexican film, “La vida de nuestro señor Jesucristo,” for example, is broadcast on the Spanish-language television station Univision during Easter week every year.

The power of film

Throughout history, Jesus has taken on the appearance and behavior of one cultural group after another, some claiming him as their own, others rejecting certain versions of him.

As the scholar of religion Richard Wightman Fox puts it in his book “Jesus in America: Personal Savior, Cultural Hero, National Obsession:” “His incarnation guaranteed that each later culture would grasp him anew for each would have a different view of what it means to be human.”

AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda

Cinema allows people in new places and times to grasp Jesus “anew,” and create what I have called a “georeligious aesthetic.” Films, especially those about Jesus, in their movement across the globe, can alter the religious practices and beliefs of people they come into contact with.

While the church and the Bible provide particular versions of Jesus, films provide even more – new images that can prompt controversy, but also devotion.![]()

S. Brent Rodriguez-Plate, Associate Professor of Religious Studies and Cinema and Media Studies, by special appointment, Hamilton College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.