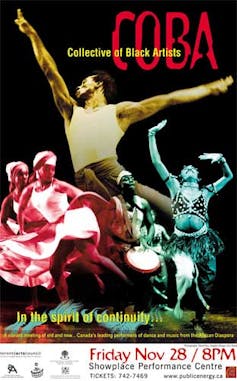

COBA Dancers: Passion through Performance, Education, and Research

COBA/Yosseif Haddad

Skin symbolizes identity — its color, shade, and texture influences cultural currency and, by extension, self-identity. When we know who we are, we can honor where we come from and we can dance in our own skins with pride and passion.

The Collective of Black Artists (COBA) is a Toronto-based professional dance company that works to extend this pride and passion through performance, education, and research.

I was one of four Black dancers with roots in the Caribbean who birthed COBA in 1993 to perform our physical and social realities. We worked to create a platform for Black dancers who were underrepresented in mainstream professional dance companies in Canada at the time. My fellow co-founders and dancers were: Bakari I. Lindsay (formerly Eddison B. Lindsay), Charmaine Headley and Mosa Neshama (formerly Kim McNeilly).

COBA injected new artistic blood into the dance scene in Toronto. It was the ‘90s, during the time multiculturalism was actively promoted within the city; it was the city’s response to the federal government’s attempt to promote unity within diversity by encouraging people to learn about other cultures despite differences in ethnicity, religion, social class. This government mandate helped to create an audience for COBA both in schools and in theatres.

COBA positioned itself as a diasporic family within the Canadian dance establishment. As a cultural membrane, COBA embraced over 50 dancers, drummers, singers and artists from Africa, the Caribbean, Canada, and Europe in the rigor necessary to perform appropriate representations of African and Caribbean dance traditions.

With reviews in The Globe and Mail, which said it was “a company that makes you sit up and take notice for all the right reasons,” COBA was a hit.

I am a dancer and Ph.D. candidate in education and I am interested in artistic vulnerability. As part of my research, I conducted interviews with some of the COBA founders and members on the significance and history of COBA. On a personal level, I wanted to explore the idea of COBA as a cultural lifeline to African and Caribbean dance heritage in Canada. What does it mean to have been part of this dance company?

It means remembering, reclaiming and honoring my ancestry and working with peers who took ownership of their history with boundless energy.

COBA’s challenges

COBA faced challenges as an under-resourced collective.

Initial funding applications were denied because an appropriate funding category for COBA’s dance form was non-existent at that time. After years of petitioning and convincing arts councils of COBA’s artistic relevance, the arts councils eventually revised their funding categories. COBA was finally able to secure grants. Still, hiring dancers full-time, year-round was not an option. Dancers still had to earn a living outside the company.

However, working within a collective is not easy. The reality in collectives is that conflicts arise amongst members. Personalities clash. Egos bruise. Some performers anchor and stay a while. Others move on to different artistic ventures, and professional pursuits.

COBA Photography, David Hou. Graphic Design, Eric Parker, Author provided

However, despite personnel changes and professional challenges that surfaced within the group, COBA persisted and maintained its integrity and mission. The key principles we followed were: Knowledge, co-operation, authenticity and endurance.

Artistic director, Bakari Lindsay described the COBA process as challenging: “Robust work demands a certain amount of consistent authority — with flexibility — in order to sustain a vision.”

The repertoire, created by Lindsay and Headley, allowed dancers to work with contemporary dance vocabularies, strengthening dancer’s physicality and technical ability. International guest choreographers were invited to stage work allowing the company to expose dancers to new movement aesthetics and fuelling COBA’s artistic growth.

Honoring African History Month

Rehearsals began in a humble studio. We carted costumes, props, drums on buses and subways en route to perform at school assemblies, most notably throughout the month of February when teachers and principals needed to fulfill the national African History mandate.

Canada is a diverse country and breaking down social and cultural barriers between communities makes a difference in how we see each other and respond to each other’s differences.

COBA’s performances sparked students’ imagination and raised students’ social awareness.

Keeping stories alive

When the drummer’s rhythms split the air and heat of the spirit rises in the performers, dances take on a life of their own, as if driven by spiritual powers. The energy of warrior spirits in the West African dances, Doun doun ba and the healing shaman in the Kakilambe come alive and transport the dancers beyond the physical realm.

David Hou

The social and historical significance of dances COBA performs demonstrates the importance of remaining flexible and adapting to new environments. Keeping stories alive through dance and drumming provides connection and memory for the things we leave behind either by choice or urgency.

While COBA’s current repertoire includes a wide variety of contemporary dance work, earlier dances were the foundation for the quality of COBA’s social and artistic exploration.

Saraca (1994), a thanksgiving ritual pays homage to the African nations who settled in the Caribbean and contributed their rites and dances to the cultural mosaic.

Non-traditional dance performance such as Portrait (1994), addresses themes of race and the human condition, underlines the problem of colourism. Griot’s Jive (2002) draws attention to gun violence which remains an acute social problem.

African perspectives for youth

The company established COBA Youth Ensemble (1994) for older/elite dancers in the children’s dance program. Together COBA and Ballet Creole created Nu-DanCe Training Program, a diverse professional dance training program grounded in an Africanist perspective.

Educating the younger generation in Africanist dance culture preserves the culture. That said, in a fast-moving dance-world social relevance is key. The invasion of hip hop and other urban dance styles commanding the global dance younger generation of dancers within the African diaspora and outside the community must know the origins of the dances they perform.

The Gwara Gwara dance, for example, performed in Childish Gambino’s video hit This is America, is originally from South Africa.

Classes in Hip Hop and Afro-beat COBA provides, ensures a new generation of dancers enjoy the dances that endorse their social relationships while promoting self-discipline and positive self-image. They will understand that the urban dances they learn and love stand on the shoulders of African dance traditions, allowing students to make connections between their past and present.

Skin imprints

Although all of the other original founders are no longer part of COBA, Bakari Lindsay and Charmaine Headley have led COBA for the past 25 years, blazing a trail from its humble beginnings to chart new ground within Canada’s dance milieu. Touring across Canada, the U.S. and the Caribbean, COBA touched, even transformed many people’s lives.

Currently COBA’s adult dance company is on hiatus. The younger generation is at the helm charting a new course for the youth. I feel privileged to have been a member of COBA. It was my diasporic family. It taught me when we dance in our own skins, we radiate our personal, spiritual and social currency.![]()

Junia Mason, PhD candidate, Department of Education, York University, Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.