How African American folklore saved the cultural memory and history of slaves

All over the world, community stories, customs, and beliefs have been passed down from generation to generation. This folklore is used by elders to teach family and friends about their collective cultural past. And for African Americans, folklore has played a particularly important part in documenting history too.

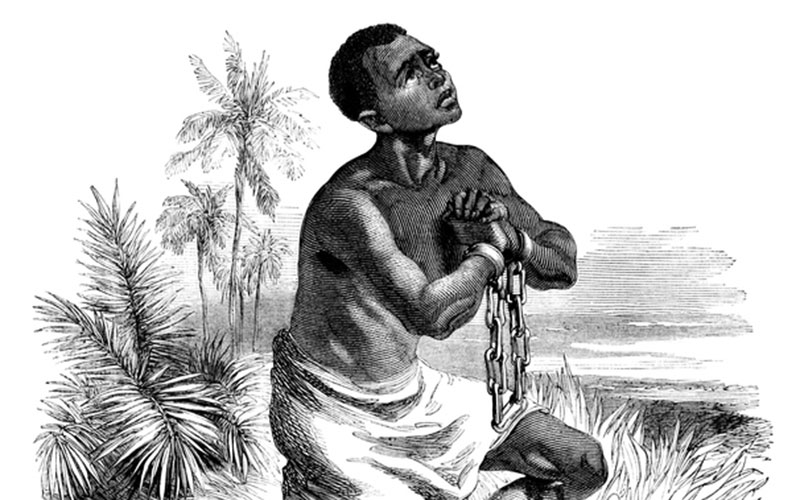

The year 1619 marked the beginning of African American history, with the arrival of the first slave ship in Jamestown, Virginia. Slavery put African Americans not only in physical shackles. They were prevented from gaining any type of knowledge, including learning to read or write during their enslavement. Illiteracy was a means to keep control as it was believed that intellectual stimulation would give African Americans ideas of freedom and independence.

The effects of slavery on African culture were huge. The slaves had to forsake their true nature to become servants to Anglo Americans. And yet, even though they were forbidden from practicing anything that related to their African culture and heritage, the native Africans kept it and their languages alive in America.

One important way of doing this was through folk tales, which the African slaves used as a way of recording their experiences. These stories were retold in secret, with elements adapted to their enslaved situation, adding in elements of freedom and hope. In the story of a slave from Guinea, recorded in The Annotated African American Folktales, he asks his white master to bury him face down when he dies, so that he may return to his home country which he believes is directly on the other side of the world:

Some of the old folks in Union County remembered that they had heard their fathers and grandfathers tell the story about Sambo who yearned to go back to Guinea. Hunters and hounds feared Sambo’s woods for more than a hundred years … I guess the hounds used to feel Sambo’s homesickness. But now, since the hounds run fast and free, I guess Sambo finally got back to Guinea.

Adapting the oral storytelling traditions of their ancestors helped slaves stolen from West Africa cope with and record their experiences in America. And later it helped other generations, particularly in the 19th century, to learn what happened to the ancestors who had been enslaved.

Folklore and genealogy

Folklore has not just helped African Americans to record and remember large-scale events, or relate morals as other folk tales do – it has helped with individual family genealogy too.

Having an aspect of genealogy in folklore makes African American history not only traceable but more approachable. The stories relate to specific people, their experiences and the places where they lived. They are not necessarily mythical tales, but stories are about real people and what happened to them. They demonstrate and track the fight for freedom and independence.

This linking of genealogy and folklore gives the oral histories continuity, and adds an element of personal curiosity to the historical past. Family history figures in many folktales makes each story unique, as one’s own heritage will be intertwined with its telling. It adds to cultural memory, too, and enhances family values as descendants are able to refer back to and honor their ancestors’ experiences. Take this extract from a retelling of The Cat-Witch, for example:

This happened in slavery times, in North Carolina. I’ve heard my grandmother tell it more than enough. My grandmother was cook and house-girl for this family of slaveowners – they must have been Bissits, ‘cause she was a Bissit.

In more recent decades, novels and book retellings of this family history have become the new way of keeping African American folklore alive. Indeed, folklore has been the inspiration behind some of the most important African American literary works. In Roots, Alex Haley’s work of historical family fiction, the main character’s father, Omoro Kinte, initiates a baptism ritual that has been transmitted throughout generations. The newborn baby is held up towards the starry night sky and then given its name. The baby is told to “behold the only thing greater than yourself”. This naming ritual is a poetic moment and has become iconic in various ways. It is even referenced in Disney’s The Lion King when Rifiki lifts Simba to the sky.

Like Roots, Margaret Walker’s Jubilee (1966) is enriched with folkloric elements. Both novels emphasize the importance of different sayings and traditions. Jubilee’s main protagonist remembers that “when she sang, the children would stop their playing and come closer to listen, for they loved all her songs – the old slave songs Aunt Sally used to sing, and the tender, lilting ballads of the war, too”. Singing folk songs was a tradition that served as entertainment or as a way to have rhythm during their work in the fields. After all, tradition is what kept the enslaved sane. Their African culture not only gave them the strength to fight for another day but it provided solace too.

For any one of us, the past is important in determining our identity and history, but without the determination and persistence of the first African Americans, it is likely that much of their story would have been lost to time. Thanks to their repeated sacrifices, African Americans can still look to their ancestors for guidance today.![]()

Jennifer Dos Reis Dos Santos, PhD Candidate, Aberystwyth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.