COMMENTARY: Learning resistance and courage from Ida B. Wells

Video courtesy of Biography

My earliest act of resistance came when I was a teenager when I was taken to the local doctor. He had a waiting room for black patients in a dimly lit hallway that was separate from the well-lit, comfortable room where his white customers waited. I would refuse to sit in the space assigned to us. There was something in my soul that made me choose standing to sitting. It was a quiet protest, but I knew what I was doing.

I may have been inspired by my mother and several other teachers in her small school in Wheatley, Arkansas, who were fired after the school was integrated because the white people preferred white teachers. My mother and that courageous group of middle-aged African American colleagues, having finally found their voices, sued the district. To their surprise, they won the lawsuit.

Long before either my mother’s or my resistance, there was Ida B. Wells, the anti-lynching activist and fearless investigative journalist who is the subject of my latest book, written with Nibs Stroupe. In 1883, when Wells was still a public school teacher herself, she was thrown out of a Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad ladies car because she was not white, though she had the proper ticket for that car. She had the courage to sue the railroad. She won the lawsuit initially but lost on appeal.

The greatest gift that studying Wells has brought to my life is freedom from fear. The plague of the 21st century is fear. Of course, there are many of us who live each day as best we can as resisters to it, but the fear hill is steep, and many are slipping down it instead of scaling it.

From 2016 to 2018, I led Calling Their Names: Remembering Georgia’s Lynched, an initiative of the Episcopal Diocese of Atlanta. We placed markers and created spaces for remembering the victims of lynchings in the state, while exploring the intersections of slavery, lynching, the prison industrial complex, the death penalty and 21st-century police extrajudicial killings — modern-day lynchings.

The initiative helps to address the issue of the moral injury that lynching brought to the nation and knocks at a door to healing that will not be opened until deep and true healing work is embraced.

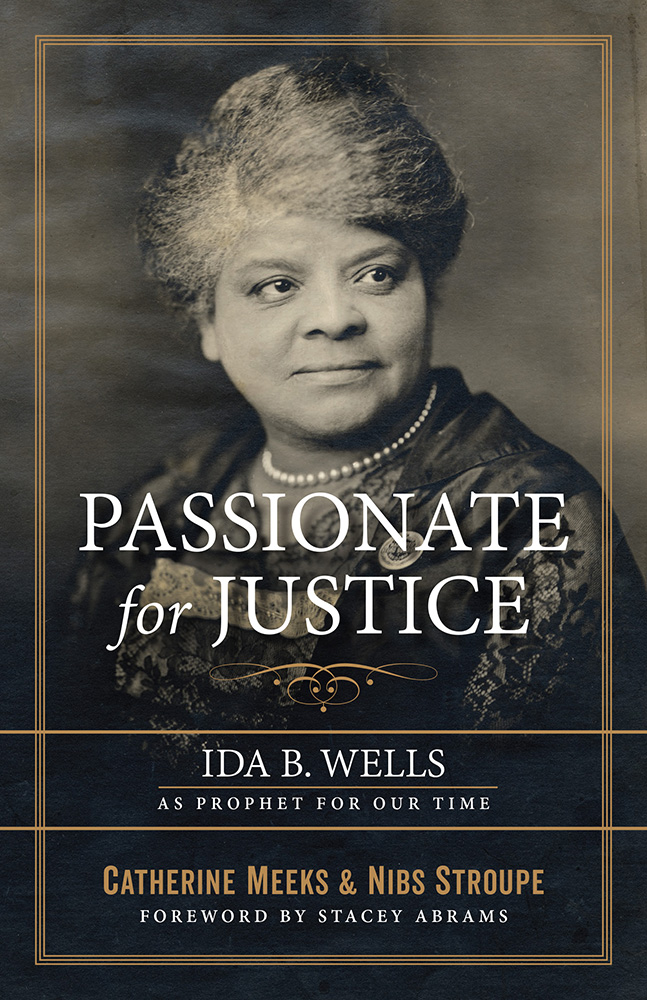

“Passionate for Justice: Ida B. Wells as Witness for Our Time” by Catherine Meeks and Nibs Stroupe. Image courtesy of Church Pub Inc

Though our work was not nearly as dangerous as Wells’, we owe her a debt. She was a pioneer in several arenas, but her work against lynching angered the white population the most because she refused to allow the white narrative, which blamed lynching on the behavior of black people, especially the men, to stand as the truth.

She laid the responsibility of the indefensible act of lynching at the feet of the white perpetrators where it belonged. She observed that “in fact, for all kinds of offenses and, for no offenses — from murders to misdemeanors, men and women are put to death without judge or jury; so that, although the political excuse was no longer necessary, the wholesale murder of human beings went on just the same.”

The kind of courage that Wells exhibited at age 16, when she took charge of caring for her siblings after her parents died, or when she fought the Chesapeake Railroad or when she returned to the South to engage in her liberation work even though she knew that there were white folks who would have killed her if given the chance is the kind of courage that must engage the powers, principalities and spiritual wickedness that the Holy Scripture speaks about in Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians.

“For our struggle is not against flesh and blood,” Paul wrote, “but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms.”

I have pondered this passage for many years, and it is clearer than ever to me how those powers are manifesting themselves in the current moment. They are supporting our collective fear and distracting too many of us from doing the work of racial healing and liberation.

Careful reading of Wells helps to deconstruct the current fear-based systems that serve the powers, principalities and spiritual wickedness in high places that stand in the path that leads to Beloved Community. She helps us to know that they cannot have the last word unless we allow them to do so. She encourages us to heed the call and to search for the inner voice that keeps telling us that nothing but true liberation is good enough for God’s children.

Wells imagined that the world could be better than it was and believed that she had a right to live in that world. I believe that the world can be better than it is and that it was never God’s intention for us to make the world that we have.

Thus, the call from God is and always will be to create a world where all of God’s children, which includes every soul on the planet, can be who they were sent to the earth to become, without being held hostage by enslaving and dehumanizing supremacists’ notions that imprison the body and the soul of far too many.

The struggle against the darkness created by white supremacy and its child, white privilege, is one to be engaged by whites and blacks, as well as all other people of color.

The journey is long, and we are far from home now, but there is a light shining at the end of the tunnel. We can catch a glimpse of that light every time we choose to embrace courage rather than fear. This realization has been one of the best sources of hope and empowerment for me. It helps me to live in a brave space where the truth can be told. It helps me to tell the truth freely, and I am encouraged every day by my dear sister, Ida B. Wells.

(Catherine Meeks is the retired Clara Carter Acree Distinguished Professor of Socio-Cultural Studies at Wesleyan College in Macon, Georgia, and director of the Absalom Jones Center for Racial Healing. This article is adapted from “Passionate for Justice: Ida B. Wells as Prophet for Our Time,” co-written with Nibs Stroupe. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)