(RNS) — Andrew Young, a former civil rights leader, Georgia congressman and United Nations ambassador, doesn’t use “the Rev.” before his name much.

But the man who directed Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference in the 1960s said every stage of his adult life has been a form of ministry.

“I have viewed everything I’ve done as a pastorate,” Young, a onetime small-church pastor, said in a Wednesday (March 2) interview. “I really thought of Congress as my 500-member church.”

Likewise, he recalled making “pastoral calls” and praying with ambassadors representing some of the 150 countries that were then U.N. members.

“My model for almost every job I’ve had has been the model of a pastor servicing a congregation,” Young said. “As the mayor of Atlanta, I just had a million-member church.”

Born into, raised in and ordained by the Congregational Church — now known as the United Church of Christ — he has been a member of Atlanta’s First Congregational Church, a predominantly Black house of worship, since 1961. As he prepares to turn 90 on March 12, he continues to preach there on the third Sunday of each month.

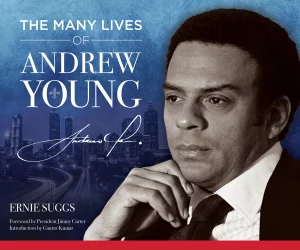

Young is marking his birthday with a four-day celebration from March 9–12, starting with a livestreamed “Global Prayer for Peace” worship service at the Atlanta church, followed by a peace walk, debut of the book “The Many Lives of Andrew Young” and a sold-out gala.

The graduate of what was then called Hartford Theological Seminary spoke to Religion News Service about voting rights battles then and now, religious aspects of the civil rights movement and his memories of working with King.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You intend to preach on peace and reconciliation to mark your 90th birthday. Has Russia’s invasion of Ukraine changed your planned message?

No, it hasn’t. Russia’s invasion has made my message even more central to the problems we’re having around the world. And Russia’s invasion is tragic and it’s even more tragic because it’s televised. But there are similar situations in many, many countries — in Latin America, Africa and other parts of Europe. And in these United States, we’re having a battle to protect the right to vote here in 2022.

You originally had plans to pursue dental school instead of seminary. What made you change your mind and do you ever regret the route you ended up taking?

My father chose dentistry. I never chose dentistry. Even as a 12-year-old, though I might have been working in a dental laboratory that my father wanted me to learn the business, I knew I didn’t want to do anything that confined me to an office. I’ve always been too full of energy and too rambunctious to stay in one place.

Even though you ended up doing ministry of different sorts, you also didn’t stay in one pulpit as some people pursuing ministry do.

We likened the ministry of the civil rights movement to the ministry of Paul and the apostles. Martin had one church. Most of us were ordained. But we pastored communities, cities, and we saw ourselves as pastors to the nation and to the world.

You were a staffer and later president of the National Council of Churches, which has risen and declined in prominence over the years. What do you consider the state of ecumenical relations now?

We have not been able to worship in our congregation for two years now. But we have (online) services, and I usually preach every third Sunday. And I get calls from as far as Switzerland and Tanzania, California, London, where friends somehow find it.

I don’t know what state the organized church is (in). But I think people are becoming and have become more seriously spiritual than at any time in my life.

The book “The Many Lives of Andrew Young” notes that when you entered the civil rights movement, you wrote, “I’ve had about enough of ‘church work’ and am anxious to do the work of the church.” Is there something about the movement’s religious aspects that many may not know?

That it was grounded in social gospel and in biblical theology. That Martin Luther King did his doctorate in the time of people like (theologians) Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr, and he carried Howard Thurman’s little book “Jesus and the Disinherited” in his briefcase all the time. And during the civil rights movement, we had worship every night.

That it was grounded in social gospel and in biblical theology. That Martin Luther King did his doctorate in the time of people like (theologians) Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr, and he carried Howard Thurman’s little book “Jesus and the Disinherited” in his briefcase all the time. And during the civil rights movement, we had worship every night.

You mentioned voting rights earlier. How do you feel about the state of voting rights, given that you helped lead the Southern Christian Leadership Conference as it sought improved voting rights and now all these years later, it’s still a topic of contention?

I’m shocked that we still have to struggle for the right to vote.

And I think that the changes in Georgia — they are structured now to steal the election. And the voting rights bills that were sent to, I think, some 30 states, they’re the same bill with the same level of corruption and the licensing of voter control. And we don’t have a Congress or a Supreme Court that’s willing to stand up now.

There’s a lot of photos in the new coffee table book about you. Are there any that relate to your religious life, your ministry, that mean the most to you?

Well, actually the one that shows me getting beat up in St. Augustine. That was probably the biggest test of my faith because I ended up leading about 50 people, mostly women and children, into a group of a couple hundred Klansmen who had been deputized by the sheriff to beat us up. I left them on one side of the street and I crossed over, trying to reason with the Klan. I was doing pretty good until somebody came up behind me and hit me with something, and then I didn’t remember anything.

But that was (shortly) before the Congress voted to pass the ’64 Civil Rights Act. And I got up and I went down to the next corner and tried to talk to the Klan on that corner. And fortunately there, when they swung at me, I ducked. And a great big policeman, biggest policeman I’ve ever seen — he was about six-six, six-seven — he walked up and said, ‘Let these people alone. You’re going to kill somebody.’ And he moved the Klan out of the way, and we were able to march.

That was one of the times that nonviolence was really on trial.

You are continuing to preach at First Congregational in Atlanta about every month — often at services featuring jazz music. It doesn’t sound like you’re anywhere near just putting your feet up at age 90.

No. There’s a song, old spiritual, that folks used to sing: “I keep so busy serving my Jesus, I ain’t got time to die.”

I just feel blessed. I have lived a blessed life. You can’t earn it, but I’ve tried to be faithful.