Video Courtesy of NowThis News

In Genesis 4, Cain kills his brother Abel out of anger and jealousy. He lured his sibling out into a field and murdered him. Then God confronts Cain and asks him where his brother is. Cain indignantly answers with a question that reverberates down through the millennia, “Am I my brother’s keeper?”

In our day in Brunswick, Georgia, two white men saw a black man, Ahmaud Arbery, out for a jog and thought the worst. They waited for him, confronted him and killed him, proving what many know and what many try to deny: white people don’t serve as their brother’s keeper but, often, as their brother’s controller.

The Hebrew word for “keeper”(שׁמר) can mean to guard or protect. To “keep” one’s brother, or more broadly, one’s neighbor, means to look out for their well-being. It means to stand alongside them as an advocate when they face difficulties and dehumanization. It means to express tangible solidarity as a sign that we are all made in the image and likeness of God.

The system of white supremacy corrupts the relationship between white people and people of color. Instead of keeping their black brothers or sisters, white people seek to control them. It is a short journey from controlling black bodies to killing them.

The alleged murder happened Feb. 23 when Arbery ran past two white men, a father-son duo named Gregory and Travis McMichael, in the Satilla Shores neighborhood of Brunswick, a small town near the Georgia coast. They reflexively assumed that Arbery was the man responsible for a string of burglaries in the area even though no such crimes had been reported in weeks. One grabbed a shotgun, another picked up a pistol, and they pursued.

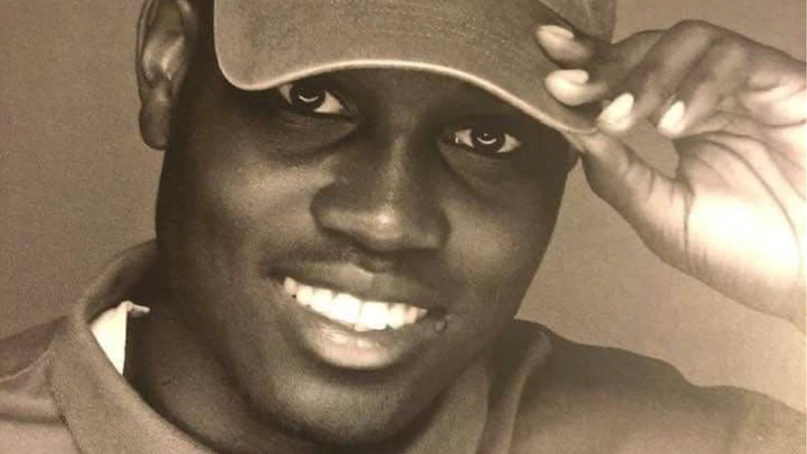

Ahmaud Arbery, in an undated family photo. Courtesy photo

The video shows Arbery jogging down the street as a white pickup truck blocks his path. The younger McMichael stands outside the truck with his shotgun. As Arbery approaches, shouts are heard, and an altercation occurs. Three shotgun blasts later, Arbery collapses to the ground.

The video emerged on May 5 and immediately sparked outrage. Within two days, the McMichaels had been arrested, after walking around free for more than two months.

What would make two ordinary citizens think they needed to take it upon themselves to get guns and pursue a black person out for a jog? If they suspected a crime had occurred, why not let law enforcement handle the situation? What role did race play in the entire scenario?

These questions all have echoes in the past. When it comes to controlling and policing black bodies, the history is as long as the nation itself.

In an article for Black Perspectives, historian Keri Leigh Merritt details the origins of professional policing in America. Prior to the Civil War, few towns had standing police forces. After the Civil War and emancipation, however, the white owner class still wanted cheap labor. They and many others wanted to re-entrench white supremacy.

White authorities devised vagrancy laws to ensnare black people in the criminal justice system. A black person could be arrested simply for not having proof of employment. Even more sinister, one did not have to be a police officer to enforce these rules.

As Merritt explained in her article, “the (vagrancy) statute deemed it lawful for ‘any person to arrest said vagrants,’ effectively giving all whites legal authority over blacks.”

This photo combo of images taken Thursday, May 7, 2020, and provided by the Glynn County Detention Center, in Georgia, show Gregory McMichael, left, and his son Travis McMichael. The two have been charged with murder in the February shooting death of Ahmaud Arbery, whom they had pursued in a truck after spotting him running in their neighborhood. (Glynn County Detention Center via AP)

Laws crafted to entrap black people in the penal system simultaneously fostered a culture of suspicion and surveillance of black bodies. White people took it as their duty and right to regulate the movement of black bodies. They claimed all spaces as “white” spaces by default, and any person of color, especially a black person, had to justify their presence.

The same dynamics were at play when, eight years ago, George Zimmerman took it upon himself to pick up a gun and pursue a black 17-year-old named Trayvon Martin. This surveillance dynamic was at work when the manager of a Starbucks in Philadelphia called the police to remove Donte Robinson and Rashon Nelson while they waited for an acquaintance to arrive for a meeting.

The culture of policing black bodies was at work when a white student called the police on Lolade Siyonbola, a graduate student at Yale who had fallen asleep in her dorm’s common room. The idea that black people must be controlled in most spaces is behind a neighbor calling the police on 12-year old Reggie Fields for mowing a portion of the wrong lawn.

White supremacy has perverted God’s command in the first chapter of the Book of Genesis that human beings should “rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.” Instead of ruling over the animals and plants as God directed, white supremacy leads people to try to rule over black people who are fellow image-bearers of God.

This culture of controlling black bodies means that just as the blood of Abel cries out from the ground for justice, so does the blood of Ahmaud cry out from Brunswick, Georgia. The blood of all the black people lynched to appease the idol of white supremacy cries out from the ground.

White people must learn, perhaps for the first time, what it means to “keep” rather than “control” their black brothers and sisters. No racial or ethnic group should have the power of life and death over another. Black bodies have been created in the likeness of God, yet our simple presence is deemed a threat to be controlled rather than a neighbor to be loved.

Only when white people learn that they are their brother and sister’s keeper rather than their controller will those cries finally be satisfied and at peace.

(Jemar Tisby is the president of The Witness: A Black Christian Collective and co-host of the Pass The Mic podcast. He is the author of The Color of Compromise: The Truth about the American Church’s Complicity in Racism.)