These NAACP leaders met at a 1916 conference. Library of Congress Anthony Siracusa, University of Mississippi

In this moment of national racial reckoning, many Americans are taking time to learn about chapters in U.S. history left out of their school texbooks. The early years of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, a civil rights group that initially coalesced around a commitment to end the brutal practice of lynching in the United States, is worth remembering now.

An interracial group of women and men founded the group that would soon become known as the NAACP in 1909. A coalition of white journalists, lawyers and progressive reformers led the effort. It would take another 11 years until, in 1920, James Weldon Johnson became the first Black person to formally serve as its top official.

As I explain in my forthcoming book “Nonviolence Before King: The Politics of Being and the Black Freedom Struggle,” interracial organizing was extremely rare in the early 20th century. But where it did take place – like in many of the summer of 2020’s Black Lives Matter protests – it was because some white Americans united with Black Americans over their shared concern about wanton violence directed against Black people.

Lynching in America

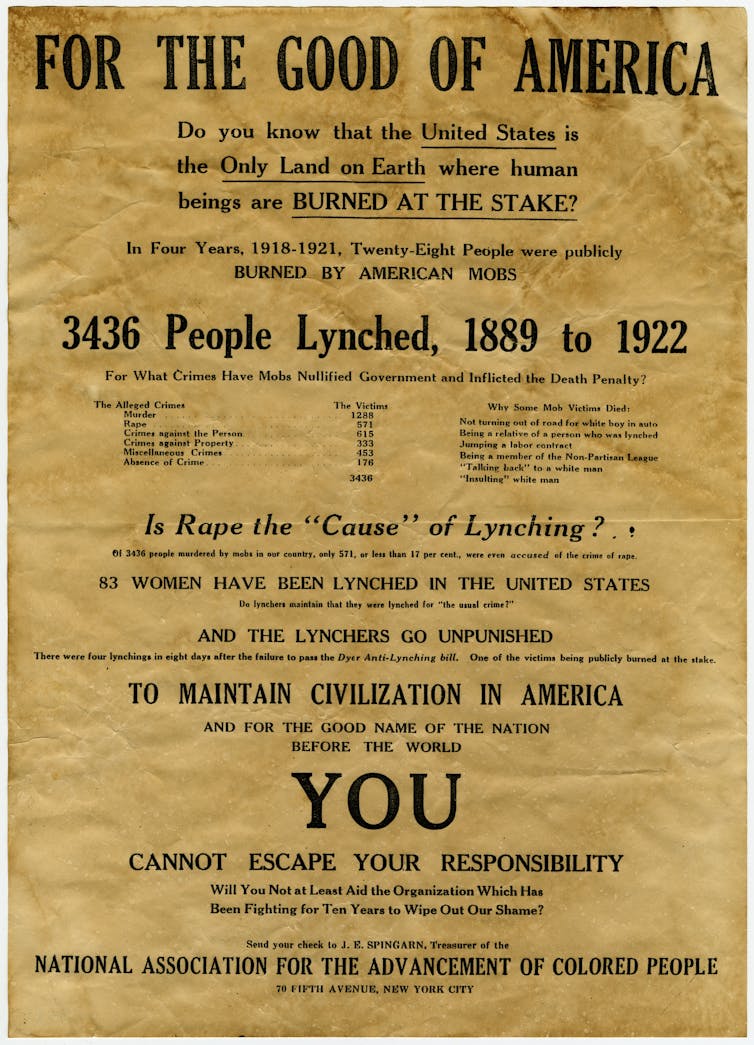

Between 1877 and 1945, more than 4,400 Black Americans were lynched. Many of these lynchings were public events that attracted thousands of spectators in a carnival-like atmosphere.

A violent attack by white people on the Black community in Abraham Lincoln’s longtime hometown inspired the NAACP’s founding. In August 1908, two African American men in Springfield, Illinois were accused without clear evidence of murder and assault and taken into custody.

When a white mob that had organized to lynch the two men, Joe James and George Richardson, failed to locate them, it lynched two other Black men instead: Scott Burton and William Donnegan. White mobs raged for days afterwards, burning black homes and businesses to the ground.

Only after Illinois Gov. Charles Deneen called in thousands of the state’s National Guardsmen was the white mob violence quelled.

‘The call’ for racial justice

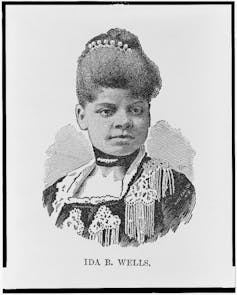

Two of the NAACP’s most prominent African American founders were W.E.B. Du Bois, a sociologist, historian, activist and author, and the journalist and activist Ida B. Wells, who had been publicly challenging lynching since the early 1890s.

They were joined by a number of white people, including New York Post publisher Oswald Garrison Villard and social worker Florence Kelley in issuing “the call” for racial justice on the centenary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth: Feb. 12, 1909.

The group organized a precursor to the NAACP known as the National Negro Committee in 1909, which built on earlier efforts known as the Niagara Movement. This loose affiliation of Black and white people called on “all believers in democracy to join in a national conference for the discussion of present evils, the voicing of protests, and the renewal of the struggle for civil and political liberty.” Du Bois chaired a May 1910 conference that led to the NAACP’s official formation.

As the historian Patricia Sullivan writes the NAACP emerged as a “militant” group focused on ensuring equal protection of under the law for Black Americans.

The NAACP’s founders, in their words, envisioned a moral struggle for the “brain and soul of America.” They saw lynching as the preeminent threat not only to Black life in America but to democracy itself, and they began to organize chapters across the nation to wage legal challenges to violence and segregation.

The group also focused its early efforts on challenging portrayals of Black men as violent brutes, starting its own publication in 1910, The Crisis. Du Bois was tapped to edit the publication, and Wells was excluded from this early work despite her expertise and prominence as a writer – an exclusion she later blamed on Du Bois.

Although the group’s early work was an interracial effort, according to historian Patricia Sullivan, all members of its initial executive committee were white.

The NAACP produced this anti-lynching poster in 1922. National Museum of African American History and Culture

James Weldon Johnson

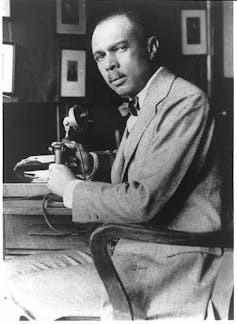

James Weldon Johnson joined the organization as a field secretary in 1916 and quickly expanded the NAACP’s work into the U.S. South. Johnson was already an accomplished figure, having served as U.S. consul to Venezuela and Nicaragua under the Taft and Roosevelt administrations.

Johnson also wrote a novel called “The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man” – a powerful literary work about a Black man born with skin light enough to pass for white. And he wrote, with his brother J. Rosamond Johnson, the song “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” which to this day serves as the unofficial Black national anthem.

As field secretary, Johnson oversaw circulation of The Crisis throughout the South. The NAACP’s membership grew from 8,765 in 1916 to 90,000 in 1920 as the number of its local chapters exploded from 70 to 395. Johnson also organized more than 10,000 marchers in the NAACP’s Silent Protest Parade of 1917 – the first major street protest staged against lynching in the U.S.

James Weldon Johnson became the first Black American to head the NAACP in 1920.

Library of Congress

These clear successes led the board to name Johnson to be the first person – and the first Black American – to serve as the NAACP’s executive secretary in November 1920, cementing Black control over the organization. He united the hundreds of newly organized local branches in national legal challenges to white violence and anti-Black discrimination, and made the NAACP the most influential organization in the fight for Black equality before World War II.

Johnson united local chapters in advocating for the introduction of an anti-lynching bill in Congress in 1921. Despite efforts in 2020 to finally accomplish this goal, the U.S. still lacks a law on the books outlawing racist lynching.

Johnson did, however, preside over the NAACP when the group notched its first of many major Supreme Court wins. In 1927, the court ruled in Nixon v. Herndon that a Texas law barring Black people from participating in Democratic Party primaries violated the constitution.

Johnson’s tenure at the NAACP’s helm ended in 1930, but his ability to unite local chapters in national litigation laid much of the groundwork for numerous Supreme Court wins in the years ahead, including the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision which marked the beginning of the end for legalized segregation in the United States.

In later years, Johnson became the first Black professor to teach at New York University.

The work continues

Among Johnson’s contributions to the NAACP was hiring Walter White, an African American leader who succeeded Johnson as executive secretary. White presided over the organization between 1930 and 1955, a period that included many successful legal actions.

The struggle launched by Du Bois, Wells and Johnson and their white allies a century ago continues today. The killing of Black Americans that led to the NAACP’s founding remains a harrowing continuity from the Jim Crow era.In 2020, 155 years after the Civil War ended, the people of Mississippi voted to remove the Confederate battle flag from their state flag, confirming an act Mississippi lawmakers undertook a few months earlier. Utah and Nebraska stripped archaic slavery provisions from their state constitutions. Alabama nixed language mandating school segregation from its state constitution.

These changes were the result of millions of Americans joining together to take action against racism, a sign that an interracial movement for justice in America has never been stronger.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.