(RNS) — Fannie Lou Hamer was an advocate for African Americans, women and poor people — and for many who were all three.

She lost her sharecropping job and her home when she registered to vote. She suffered physical and sexual assaults when she was taken to jail for her activism. And stories of her struggles reached the floor of the 1964 Democratic Convention — and the nation — when her emotional speech aired on television.

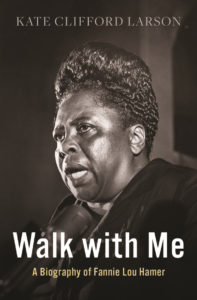

Historian Kate Clifford Larson has written a new book, “Walk With Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer,” that reveals details of the faith and life of Hamer, who was born 104 years ago Wednesday (Oct. 6) and died in 1977.

“Walk with Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer” by Kate Clifford Larson. Courtesy image

Inspired by young Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee workers who preached Bible passages about liberation at her church in Ruleville, Mississippi, in 1962, Hamer became a singer and speaker for equal rights and human rights.

“She crawled her way through extraordinarily difficult circumstances to bring her voice to the nation to be heard,” Larson told Religion News Service. “And she knew that she was representing so many people that were not heard.”

Larson spoke to RNS about Hamer’s faith, her favorite spirituals and how music helped the activist and advocate survive.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you decide to write a biography of Fannie Lou Hamer and how would you describe her as a woman of faith?

I published a book about (Harriet) Tubman and Hamer is so similar to Harriet Tubman, only 100 years later. I decided to start looking into her life and thinking I should do a biography of Hamer. I just became hooked. There were so many similarities, and things I could see in Hamer that I just thought, we need to have a refresher about Fannie Lou Hamer and the strength of her character and how she survived such incredible adversity and found the same kind of solace that Harriet Tubman did — in her faith, in her family and the community — to keep going and fighting and to try to make the world a better place.

It seems she is relatively unknown in many circles despite the credit she’s given by civil rights veterans for her work.

It is curious that she is not well known broadly. And I hope that changes, because I think we need to look back sometimes to see how far we’ve come. And with Hamer, the things that happened to her — she faced the world by confronting that trauma, and that violence, without hate. And the only way she could do that was through her faith, and talking to God and saying: Where are you, what is happening here, give me the strength to carry this weight and to move forward. And she did. She knew hate could really destroy her — that feeling of hating the people that were trying to kill her and subjugate her. She managed to rise above it because she had a greater mission in front of her.

Why did you title the book “Walk With Me”?

The title is from the song “Walk With Me, Lord.” She was brutally beaten, nearly killed, in the Winona, Mississippi, jail in June of 1963. As she lay in her jail cell, bleeding and bruised and coming in and out of consciousness, she struggled to hang on and her cellmate, Euvester Simpson, a teenage civil rights worker, was there with her. She asked Euvester to please sing with her because she needed to find strength and she needed God to be with her. So she sang that song “Walk With Me, Lord.” She needed to feel there was something bigger that would help her survive those moments where it wasn’t so clear she would survive. And I found it so powerful that she would do that. She survived that night and was able to get up and walk the next morning.

What other spirituals and gospel songs were particularly important to Hamer as she fought for voting rights and other social justice causes?

One of her favorites is “This Little Light of Mine.” She sang that everywhere, all the time. It’s kind of her anthem. There were some other spirituals, but really, most of the ones she sang a lot during the movement were those crossover folk songs, rooted in Christian spirituals, like “Go Tell It on the Mountain.” She grew up not only in a very strong church environment, the Baptist church, but she grew up in the fields of Mississippi where there were work songs in the fields, call and response songs. Where she grew up was actually the birthplace of the Delta blues music.

She also quoted the Bible to the people she differed with. Were there particular biblical lessons Hamer applied to her fight to help her fellow Black Mississippians?

She used the Bible in many different ways. She used it to shame her white oppressors who claimed also to be Christians, following the path of Christ. She would use the Bible and say: Are you following this path by what you’re doing to me, to my fellow community members and family members? And she used the Bible passages to remind Christian ministers: This is your job, and what are you doing up on that pulpit? You’re telling people to be patient. Well, in the Bible it says stand up and lead people out of Egypt.

You wrote about William Chapel Missionary Baptist Church, Hamer’s congregation, throughout the book. What happened there, over the years as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and other groups used it as a place for meetings, classes and rallies?

The church, the ministers participated in the movement and had meetings in that church at great risk to themselves and to the church, and in fact, the church was bombed a couple of times even though the fires were put out, fortunately, very quickly. There were residents in the community that took their lives and put them on the line. They were at great risk, to go to those meetings, to conduct those meetings, to go out and do voter registration drives. It was all centered on the church community because that was really the only community buildings in many of these places where people could meet together to have these discussions.

You said Hamer was at a crossroads as she first listened to those SNCC (pronounced “snick”) activists seeking more people to join their cause.

She experienced trauma, and she had been sterilized against her will — she didn’t give permission — and she had gone through this very deep depression, and it tested her faith. It tested her understanding of the world, and she came out of that and went to this meeting in Ruleville in 1962 and when she heard those young people and their passion and their willingness to put their lives on the line for her, she viewed them as the “New Kingdom.” So it was more than a crossroads for her. It was a moment where she could see the future in these young people, and she called them the “New Kingdom (right here) on earth.” If they were willing to stand up and risk their lives then she could, at 45, 46 years old, stand up herself. That was a crossroads. She made that choice to stand up, publicly, and move forward.