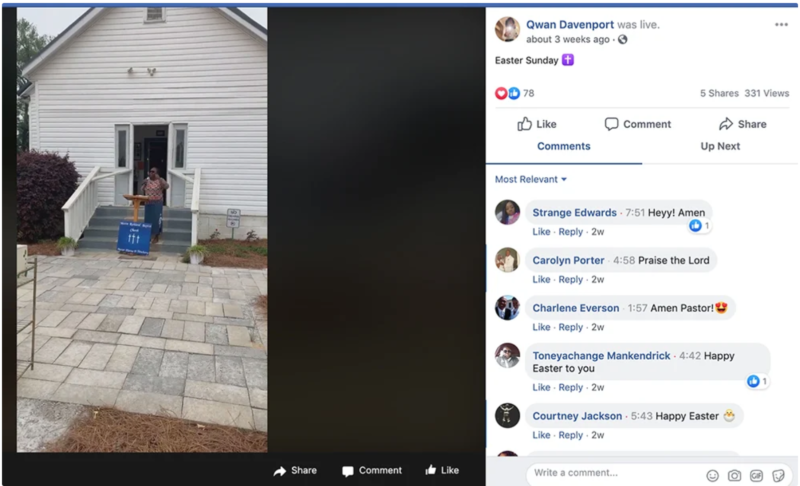

Pastor Florine Newberry delivers her Easter Sunday message from the doorway of Mattie Richland Baptist Church, April 12, 2020, streamed via Facebook Live in Pineview, Georgia. Video screengrab via JaQwan Davenport

When Pastor Florine Newberry of Mattie Richland Baptist Church in rural Pineview, Georgia, realized her congregation wouldn’t be able to meet in the church’s blue carpeted sanctuary due to the coronavirus pandemic, “I just saw the sheep scattering,” she said.

Many of the 45 to 50 members of Newberry’s independent church do not have computers or home access to the internet. Though some own cellphones, cellular service is often spotty in the rural flats more than two hours south of Atlanta.

Her worst fears were quieted when some parishioners took to gathering 6 feet apart in their cars on sunny Sundays to hear Newberry preach.

But once Mattie Richland Baptist became one of 46 predominantly black churches in Georgia to receive help gaining internet access from Fair Count, an organization founded to increase participation in the 2020 census in hard-to-count areas, Newberry’s great-nephew — and Sunday school teacher — said he could use his phone to livestream her sermons.

Pastor Florine Newberry. Courtesy photo

When Newberry preached her Easter sermon from the doorway of her church, her message was viewed by hundreds of people via Facebook Live thanks to the Fair Count hot spot.

“That hot spot from Fair Count, and through the blessings of God that watches over Mattie Richland, has allowed me to have peace of mind that I can still reach out to people,” said Newberry.

America’s black clergy, like their counterparts in houses of worship across the country, have heard the call to pick up the tools of Zoom, Facebook and other social media as a workaround for in-person worship and Bible study. But with issues of access and technical ability among some congregants, and a pandemic that has closed their church doors and scattered congregations, African Americans have been scrambling to sustain crucial connections to their houses of worship.

“If you look at websites, Facebook, other media, white churches are better positioned, it seems, to connect their people and to connect to their people than black churches going into this crisis,” said Mark Chaves, director of the National Congregations Study, citing data from 2018-19.

That advantage has widened the religious digital divide. A new survey from Pew Research Center shows that while 92% of evangelical Christians and 86% of mainline Protestants say their church offers streaming or recorded services online, only 73% of Protestant worshippers in the historically black tradition say they can watch religious services remotely.

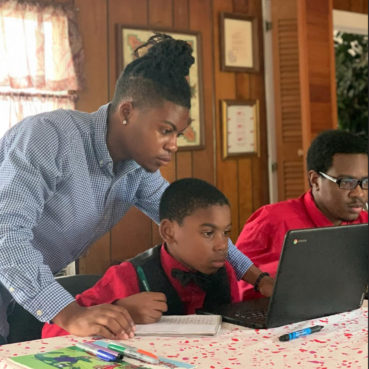

Sunday school teacher JaQwan Davenport, left, works with youth on a donated laptop at Mattie Richland Baptist Church, in Pineview, Georgia, before social distancing was required to combat the coronavirus. Courtesy photo

Access to digital resources is not solely a problem in rural areas. The Rev. Boise Kimber, senior pastor of First Calvary Baptist Church in New Haven, Connecticut, has worked to get churches websites since 2016. But during the pandemic, Kimber initially chose not to use livestreaming, knowing many of his inner-city church members did not have access to a computer. His church later added Zoom as another option to reach younger members.

“I’m trying to reach individuals that support our ministry, spiritually and financially,” said Kimber. Those people, he said, are available largely by phone.

Pastor Brenda Lacy, leader of Greater Revelations Worship Center, a multicultural inner-city church in Kansas City, Missouri, said she knew her 50 members, including the elderly, could be reached via conference calls on their phones because it was how they gathered remotely for prayer calls three times a week.

“I’m not sure if every member has internet access, but they do have access to the conference line,” she said. “The only thing that has changed with that is that we’re doing our morning worship on there, we’re doing our Bible studies on there, we’re doing everything there.”

Nona Jones. Courtesy photo

Nona Jones, head of Facebook’s global faith-based partnerships, said Facebook has seen a “pretty major spike in the spiritual pages” used by faith communities in recent weeks. Sensitive to those limited to phones, Facebook has begun making available a free service that allows churches to provide a phone number for people who do not have reliable internet or strong bandwidth to view a livestream.

“The feedback we’ve heard so far, even using it in our own church, is that there’s a lot of older people who have felt connected who were feeling isolated,” said Jones, who in addition to her Facebook job is co-pastor of a church in Gainesville, Florida. “But being able to even listen to our voices has given them a sense of hope and a feeling of community.”

The elderly are most at risk and least likely to be able to link to their churches online.

“There is definitely some exclusion that’s taking place when it comes to older congregants, especially those who used to get picked up by the bus and brought into worship,” said Elonda Clay, a Ph.D. candidate in theology and religious studies who has studied the black church and technology trends.

Elonda Clay. Photo by Dirk van der Duim

Clay pointed to her 80-year-old father, a longtime member of a “small United Methodist church of 80-year-olds,” who was only able to phone into a Sunday worship conference call after someone called him to inform him the first one had occurred.

Some churches have found that improving their internet connections can also improve their spiritual connections with a younger generation. “As younger people are not going to service in the same numbers that, say, the baby boomer generation went,” said the Rev. Barbara Williams-Skinner, co-convenor of the National African American Clergy Network, “streaming is the ideal way — this is pre-COVID — for reaching younger church people.”

If nothing else, the pandemic is showing many churches the power of the internet, whatever their bandwidth. Brother Marcus Tolliver of Browns Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Chester, South Carolina, said that coronavirus has prompted a sea change in his church, which previously used its Facebook page to post daily phrases of inspiration and photos from church events. If a service was recorded, it would be distributed on DVDs or CDs.

Last week, he led his congregation of 275 in a two-night online revival, using his iPhone when the internet service proved to be poor at the church.

Brother Marcus Tolliver, bottom right, of Browns Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, moderates a “Focusing on the Mind” panel via Zoom and Facebook Live on April 25, 2020. Video screengrab

The next day, Tolliver moderated on Zoom and Facebook a “Focusing on the Mind” panel on black churches and mental health that drew more than 2,400 views. On Sunday (April 26), the church converted its annual “pack-a-pew” service to “pack-a-page” on Facebook Live, with more than 1,000 views.

“This is definitely new territory,” said Tolliver. “We’ve learned to do things that we never thought we’d do. Some of these older preachers in the more rural communities, they’ve learned to work technology they never expected that they would have to work. They’ve learned how to have Zoom meetings with their church families, and they’ll have Bible study and they can still see each and every one of their members. Before COVID-19, that wasn’t even a thought.”

Jeanine Abrams McLean. Courtesy photo

For Georgia churches like Mattie Richland Baptist, the efforts of Fair Count, founded in Atlanta by former Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, have shown how improving internet access for churches can be a boon to the entire community, sometimes in unexpected ways.

Jeanine Abrams McLean, vice president of Fair Count and Stacey Abrams’ sister, said the organization has established 135 internet access points using hot spots and tablets donated to churches, barbershops and community centers across Georgia, where about 20% of people have only broadband access or lack internet entirely.

Besides internet access, McLean said, the nonprofit, backed by grants from foundations and private donors, has begun providing free church management software that clergy can use to communicate with members and to facilitate online giving.

“Even if a church doesn’t have internet access, if we’re able to give it to a pastor that has internet access, then they can send out text messages to their parishioners that way,” McLean said of the program that has aided a few dozen houses of worship from Nevada to Mississippi to Illinois. She hopes to extend the service to several hundred more over the next four years.

After receiving a Fair Count hot spot, the Rev. Bo Barber II, pastor of Prospect African Methodist Episcopal Church in Fortson, a suburb of Columbus, Georgia, saw that it could help with more than the census.

The Rev. Bo Barber III, of Fortson, Georgia, speaks in Atlanta at a May 2019 “Black Men Count” event about the 2020 census. Courtesy photo

“When the schools closed, there were a number of children that needed to have access to broadband in the communities and in the area,” Barber said. Now, he explained, “our community can drive up into the parking lot” and draw connectivity from their cars. In the last few weeks, 40 families have visited the church lot.

“Knowledge is power,” said Barber. “And if you’re isolated, you’re not empowered.”