AP Photo/Bebeto Matthews

As the COVID-19 pandemic spreads, global religious leaders have been advised or compelled to shut the doors of their places of worship. In many places, public worship has come to a halt for the first time since the 1918 influenza pandemic — although even then, some cities insisted that churches needed to stay open.

While some Christian priests and pastors have insisted on meeting in their churches, many churches and other Christian groups globally are looking to build some form of online presence to share the gospel without spreading the virus.

Rev. Janet Cox, a deacon at St. Paul’s Methodist Church in Brooklyn, N.Y., delivers her sermon from an empty church to home-bound congregants by a livestream broadcast, March 22, 2020, in New York. (AP Photo/Bebeto Matthews)

For Jews, Christians and Muslims, COVID-19 hit at an especially hard time. Ramadan, Passover and Easter are coming soon. For members of these communities, these are among the holiest seasons of the year.

Whether it will be Muslims breaking the Ramadan fast over WhatsApp, Jewish families sharing a Seder on Skype or Christians typing “Jesus is risen indeed!” in an Easter morning Zoom chat, the pandemic promises to make this religious season a first.

Virtual religion is ancient

Virtual religion, however, is not new. It’s actually pre-internet, even pre-electricity. Medieval cloistered nuns and monks took pilgrimages by reading travellers’ accounts and pacing the distance to Bethlehem or Rome in their cells. The differently abled have long participated in their communities of worship through radio, television, audio recordings and the telephone.

Among the first reports of Christians praying and worshipping online were some whose experiments were also driven by tragedy. The very oldest act of online Christian worship might well be a Presbyterian memorial to the Challenger space shuttle disaster in 1986. Death and grief are powerful engines of religious change, and have often provoked the emergence of new spiritual attitudes to media and technology.

Since those early experiments, online church communities have flourished, including livestreams, chatrooms and virtual worlds. In 2004, the Methodist Council in the U.K. funded Church of Fools, an avatars-in-church project that transitioned into St. Pixel’s website, and then a same-named Facebook group and network. The same year i-church launched, as “an experimental online community” that is part of the Church of England.

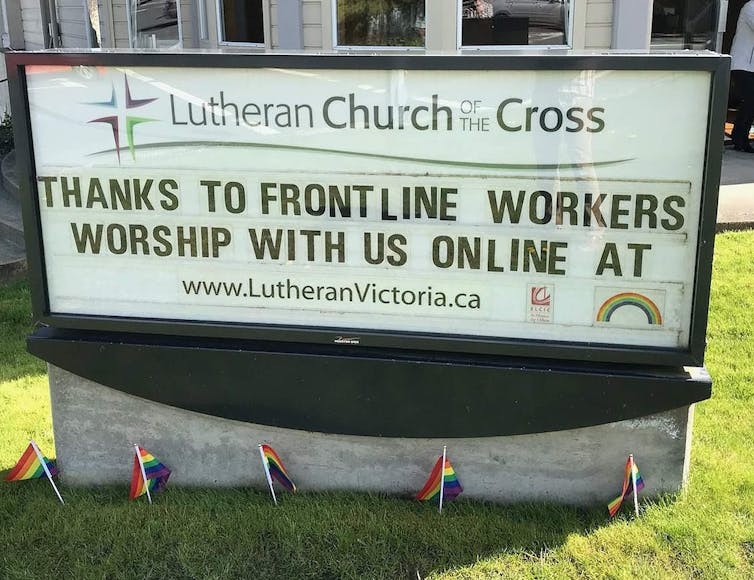

Lutheran Church of the Cross, Victoria, B.C., shows a sign reading ‘Thanks to frontline workers. Worship with us online,’ next to a rainbow showing it’s a ‘queer-affirming’ church. (Matthew Robert Anderson), Author provided

There’s a lot of talk about online religion being “unprecedented.” It’s not. What is unprecedented is religious groups all over the world all doing it at the same time.

Here are six proposals about digital religion from a theologian and a sociologist, who has written a book about online churches:

1. People return to online spaces that give them experiences worth repeating.

This might mean world-class preaching or music. But it’s more likely to mean community, friendship, a place to feel valued and the chance to get meaningfully involved. If an online church doesn’t find a way to help visitors feel they are part of a community, it won’t work.

2. Going online means new opportunities to be more accessible and open.

In their now-shuttered physical places of gathering, traditional faith groups struggled with being welcoming and inclusive. Many of the pioneers of online faith communities challenged religious exclusivity, providing a home for Christians who felt they did not belong elsewhere.

Online churches have attracted Christians with diverse theologies and sexualities, neuroatypical and disabled Christians and people who had rejected — or been rejected by — local churches. The COVID-19 crisis presents an unparalleled opportunity for all churches to be more accessible and open to groups historically excluded from their pews, while taking care to accommodate and consider people’s varied levels of digital literacy.

3. Online diversity needs protection.

Online communities and networks also make space for hate and harassment, as some communities now rushing into live-streaming have begun to discover. Secure software, responsible codes of conduct and watchful moderators are essential, even if finding them takes time.

4. Reproducing “normal” worship isn’t a bad start.

Despite the wide-open visual possibilities of virtual design before them, the first Christian congregations to form in virtual worlds still created recognizable cathedrals and medieval-looking church spires.

Especially in times of crisis we tend to prefer what feels familiar and authoritative. In the first weeks of the pandemic, it is no surprise that many religious groups chose to livestream bare-bones versions of their regular activities, featuring music, a speech and readings one could follow at home.

5. “Normal” will change.

Tim followed a small group of online churches for more than a decade. He learned that the most successful survive because they are willing to experiment. Each of those churches started with something familiar, then built the confidence to adapt to their new medium.

The term virtual sometimes implies “less-than” — but digital faith communities insist their online experiences are more than just a simulation of what happens in a local church. New ideas, new worship practices and the new theological interpretations supporting them take time to mature.

For example, for Christians whose regular gatherings are centred around shared communion, online-only gatherings have provoked debates about its meaning. For many, communion is a moment when bread and wine are consecrated and understood as a “sacrament,” where Christ is present. Christians are now wrestling with what it means for that presence to be encountered online.

Arguments about the meaning of communion are as old as Christianity itself, and discussions about digital communion have been underway for decades. Amid the new normal of the pandemic, at least one major Christian institution has suggested that online communion might be acceptable after all.

6. Experience is out there.

In almost every religious community, there are those who have spent decades exploring the possibilities of virtual religion but they will often not be found in denominational headquarters. Churches can find these experts, and learn from them.

Rev. Christian Rauch, priest at St. Andreas Catholic Church in Lampertheim, Germany, stands in front of photos with parishioners on April 4, 2020. AP Photo/Michael Probst

Promise and peril

A memorable image from the first week of enforced distanced worship was of a Catholic priest in Italy who printed colour photographs of his congregation and taped them to chairs in the church sanctuary. He stood, arms stretched wide in prayer, before all these faces. Around the world, other churches rushed to copy that extraordinary gesture.

As inspiring as this act was, it was immediately turned into a Twitter meme that picked up on petty politics in church communities to joke that someone “complained another person’s photo was in their spot.” The priest and his heckler show both the promise, and the peril, of the digital transformations.

Will digital worship become a chance to radically rethink what it means to be both faithful and in community? Or in the rush to the web will it simply be the same-old institutional thinking wrapped in a new format? Only time will tell. As the first online Easter for so many of the faithful quickly approaches, Christians are about to find out.![]()

Matthew Robert Anderson, Affiliate Professor, Theological Studies, Loyola College for Diversity & Sustainability; Honorary Research Associate, University of Nottingham UK, Concordia University and Tim Hutchings, Assistant Professor in Religious Ethics, University of Nottingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.