On a beautiful spring afternoon on a picturesque college campus, two campus police officers responded to a black professor’s “good afternoon” with a request to see his identification.

The professor paused for a moment but decided to comply. He wondered if perhaps his attire – slacks, a button-down shirt and loafers – didn’t signal that he belonged.

As he presented his ID, another group of colleagues – all white – arrived and asked what was happening, so the professor told them. His colleagues asked the officers – in a sarcastic way – if they needed to show identification as well. The officers hurriedly returned the professor’s ID and didn’t respond to his colleagues’ inquiries.

This isn’t fiction. It happened to one of us. We are researchers with a keen interest in how race comes into play during day-to-day interactions with police both in and outside of college campuses.

Outsiders on campus

College campuses are often thought of as safe spaces and commonly regarded as forward-thinking environments. However, as our anecdote and recent events demonstrate, merely being a student or even a faculty member does not always equate to acceptance and inclusion, particularly if the student or professor is a member of a minority group on campus.

Consider, for instance, two recent incidents on college campuses that involved racial profiling by proxy – that is, instances where police are summoned to a situation by a biased caller. One incident took place in Colorado on the campus of Colorado State University during a campus visit and tour. Two prospective students, who were Native Americans males, were accused of acting “odd” due to their quiet disposition and clothing by a parent of another student on the campus tour. Due to her heightened suspicions, she called the police on the two teens. The other incident took place in Connecticut on the campus of Yale University. In this instance, a white student called the police on a black female graduate student who took a nap while writing a paper in their dorm’s common room.

Both cases serve to show how racial micro- and macro-aggressions aren’t limited to neighborhoods. They surface on college and university campuses as well. These recent incidents come not even two years after the hashtag #BlackOnCampus flooded Twitter, exposing the daily occurrences of racism experienced by black students, and leading to protests focused on race relations on over 50 college campuses.

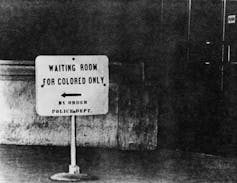

Campuses have often been described as “microcosms of society,” so these incidents send a troubling message that the racist attitudes and behaviors that were part and parcel of American history endure in the present. They also highlight the need to move beyond policies addressing the legal restrictions that historically limited access to spaces and places to certain racial groups. Moving beyond this negative aspect of our nation’s past requires a shift in the current discussion from one that focuses on law enforcement and campus safety towards one in which we candidly discuss shared historical fallacies about the much-maligned “other.” This unpacking necessitates an understanding of how we, as a society, got to where we are today.

The myth of black criminality

From a historical perspective, American society was based on social constructions of race, ethnicity, gender and other identities. As a result, an American narrative that defined being different from the majority as deviant became embedded within the framework of American society, as well as the nation’s legal system. One example of this that appeared after the Civil War was the enactment of the black codes, which greatly restricted blacks’ labor and movement. The different-as-deviant narrative still affects American society to this day. Public policies and governmental actions have often reinforced these notions of “otherness” by marginalizing those who are considered undeserving and uncapable.

Everett Historical/www.shutterstock.com

Human beings have often been described as having an affinity for myths. One myth that continues to permeate society is known as Black Crimmythology – or the myth that conflates blackness or otherness with criminality. Black Crimmythology, as the converging legacy of the social construction of race and the stigma that accompanies it, continues to blemish our society. As such, it has a constraining limiting effect that impacts a person’s meaning, destiny and value – all based upon their physical appearance.

Political constructions are public policies that were created to reinforce the social construction of Black Crimmythology. Public policies – both before and after the Civil War – limited the spaces and places to which blacks and other people of color had access, with criminalizing effects. Implementing Black Crimmythology and the policies that legally reinforced it required the assistance of public servants – that is, law enforcement officers – and the support of white citizens who made up the dominant class.

The incidents at Colorado State University and Yale University highlight how all these things – race or Black Crimmythology, practices of contemporary police officers and “support” from members of the dominant racial group – resulted in a negative interaction or encounter. The police were called to address each caller’s implicit or explicit bias or prejudiced anxieties. These incidents reflect the lasting nature of the old narrative of defining one who is different as deviant, even during what some have described as our post-racial or post-black society.

Toward ‘brave’ spaces

In order to make progress and lessen the potential for negative encounters between members of minority groups and campus police, society must be willing to enter into brave spaces – that is, spaces where people find the courage to risk engaging in uncomfortable and unsettling dialogue around issues of race and racism.

This effort requires more than just acknowledging the pain of others, but actually acting upon it.

One tool that can help in this regard is the Handy Guide for Objective Threat Evaluation developed by Hobart Taylor and utilized by the University of California-Irvine Police Department. This tool asks that prior to calling the police, members of the public should ask themselves a series of questions: Does someone seem suspicious because of something that they are doing? Does someone seem suspicious because of how they are behaving? Or, is it because of their appearance? If it is because of their appearance and not because of their behavior, the assessment advises not to call.

![]() This tool was created to help the public identify when situations and incidents necessitate calling the police. If the callers at Colorado State and Yale would have followed this guide, officers never would have been called in the first place.

This tool was created to help the public identify when situations and incidents necessitate calling the police. If the callers at Colorado State and Yale would have followed this guide, officers never would have been called in the first place.

Brian N. Williams, Visiting Professor of Public Policy, University of Virginia; Andrea M. Headley, Presidential Postdoctoral Fellow, University of California, Berkeley, and Megan LePere-Schloop, Assistant Professor, The Ohio State University

This article was originally published on The Conversation.