Faith leaders push back against proposed ‘Souls to the Polls’ voting restrictions

Video Courtesy of The Choice

To the Rev. Fer’Rell Malone of Waycross, Georgia, the actions by his state legislators that could curtail Sunday “Souls to the Polls” activities are akin to a form of apartheid.

“They are literally evil, and they’re coming from men and women who say that they are Christians,” the Black pastor told reporters Wednesday (March 10) in a virtual news conference.

He said the lawmakers are focused on reducing effective strategies Black churches have historically employed to mobilize voters.

“They’re trying, with the voter suppression laws, to create a system of apartheid where they who have the power will retain the power,” he said.

RELATED: Biden victory in hand, Black church get-out-the-vote workers assess the future

Malone’s is one of more than 500 signatures on a Faith in Public Life petition delivered to Governor Brian Kemp that condemns proposed changes in voting policies they say will particularly harm people of color.

The Georgia House bill, which passed the Republican-majority body by a vote of 97-72 on Monday, would permit at least one Saturday for voting near the time of a future Election Day but would allow registrars to choose whether to offer voters an additional Saturday or Sunday to vote.

In recent elections in the state, Black church leaders have spearheaded “Souls to the Polls” campaigns that led worshippers directly from their pews to their polling places.

The nonpartisan Brennan Center for Justice reported this month that Georgia’s Black voters accounted for 36.5% percent of Sunday voters but only 26.8% of people who voted early on other days of the week.

Former Georgia House Minority Leader Stacey Abrams said this week there are more than 250 bills related to voting restrictions being considered by state legislators across the country.

Georgia’s House and Senate proposals, which Abrams said would particularly harm people of color, relate not only to Sunday voting but also would eliminate automatic voter registration and no-excuses absentee balloting and would require a copy of a driver’s license with mailed-in ballots.

“Black people, people of color have always been the target of voter suppression because it is when we lift our voices, it is when we participate in elections, it is when we have the right to full citizenship that the trajectory of this nation changes,” Abrams, who has a United Methodist background, said Tuesday on a Facebook Live program hosted by the African Methodist Episcopal Church’s newspaper, The Christian Recorder.

In January, the Rev. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff, her state’s first Black and Jewish senators, respectively, were sworn in, giving the U.S. Senate a Democratic majority. Two months before on Election Day, a record Black voter turnout helped flip the Peach State from red to blue for the first time since 1992.

The Georgia state legislators are also proposing limitations that would criminalize volunteers — who are often connected to faith groups — if they provide food and drink to voters waiting in line outside polling places.

“The lines were so incredibly long that we had multiple reports of people fainting in lines for having to stand up for too long,” said Fair Fight Action organizing director Hillary Holley of the 2020 election, speaking during the news conference. “We saw ambulances have to get called because our elders were passing out while trying to vote.”

The Rev. Cassandra Gould, an AME minister who is the executive director of Missouri Faith Voices, said in an interview that her group has been fighting laws restricting voting, including as a co-plaintiff in a suit against the secretary of state that was dismissed on Tuesday.

Though Missouri doesn’t have early voting as Georgia does, Gould said her organization continues to oppose other kinds of voting restrictions that she says disproportionately affect African Americans. In February, the Missouri House passed a bill that requires voters to provide a photo ID or cast a provisional ballot.

“For me it’s really egregious when there are concentrated efforts to minimize democracy, to actually shrink the electorate,” said Gould, who is also the religious affairs director for the state’s NAACP chapter.

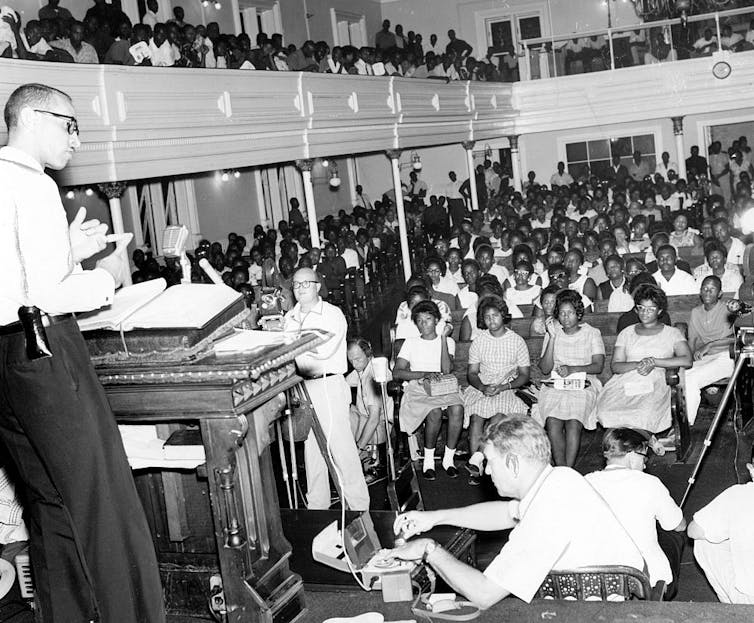

The developments in Georgia came during the anniversary week of Bloody Sunday, when church leaders and other civil rights activists were attacked by state troopers as they fought and bled for voting rights in Alabama in 1965.

Min. Shavonne Williams, an Augusta-based organizing ambassador for Faith in Public Life, recalled that historic time and said voting has long been a unified front for Black church members.

But, in addition to concerns about Black voters, the legislators’ actions have prompted questions about constitutionality and religious freedom, according to Graham Younger, Georgia director for Faith in Public Life.

Early weekend voting opportunities are vital to many residents who are unable for various reasons to vote on a weekday. Limiting which weekend day polls may be open, however, can affect worshippers of a variety of faiths and racial/ethnic groups, including Jewish congregants and members of Seventh-day Adventist churches who cannot vote on Saturdays, due to Sabbath restrictions.

“The choice that counties will now be making is between different groups’ holy days,” Younger said. “Not everyone’s holy day is Sunday.”

Conservative religious groups, including Family Research Council, support “ election integrity ” state-level provisions such as ones that require voter identification and limit no-excuses mail-in voting.

Pastor Mike McBride, a Pentecostal minister based in California who was involved in 2020 Black church voter mobilization initiatives, said organizers are pushing back against legislators seeking to reduce “Souls to the Polls” and other activities.

As they work on signing letters and raising awareness about state proposals, they also will urge passage of the For the People Act, which he hopes will “take the teeth out of a lot of these very wicked Republican schemes.”

“I believe this is tantamount to the church bombings the Ku Klux Klan did to terrorize Black people from engaging in voter registration and engagement,” said McBride, a founder of the Black Church Action Fund, in an interview. “Rather than using church bombs, they’re trying to use these kinds of state policies.”