Her Biopsy Report was Benign, But the Bill is a Spot of Contention.

While living in Detroit earlier this year, Brianna Snitchler wanted a cyst removed from her abdomen. But her doctor wanted the growth checked for cancer first. (Callie Richmond for KHN)

Brianna Snitchler was just figuring out the art of adulting when she scheduled a biopsy at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

Snitchler was on top of her finances: Her student loan balance was down and her credit score was up.

“I had been working for the past three years trying to improve my credit and, you know, just become a functioning adult human being,” Snitchler, 27, said.

For the first time in her adult life, she had health insurance through her job and a primary care doctor she liked. Together they were working on Snitchler’s concerns about her mental and physical health.

One concern was a cyst on her abdomen. The growth was about the size of a quarter, and it didn’t hurt or particularly worry Snitchler. But it did make her self-conscious whenever she went for a swim.

“People would always call it out and be alarmed by it,” she recalled.

Before having the cyst removed, Snitchler’s doctor wanted to check the growth for cancer. After a first round of screening tests, Snitchler had an ultrasound-guided needle biopsy at Henry Ford Health System’s main hospital.

The procedure was “uneventful,” with no complications reported, according to results faxed to her primary care doctor after the procedure. The growth was indeed benign, and Snitchler thought her next step would be getting the cyst removed.

Then the bill came.

The Patient: Brianna Snitchler, 27, a user-experience designer living in Detroit at the time. As a contractor for Ford Motor Co., she had a UnitedHealthcare insurance plan.

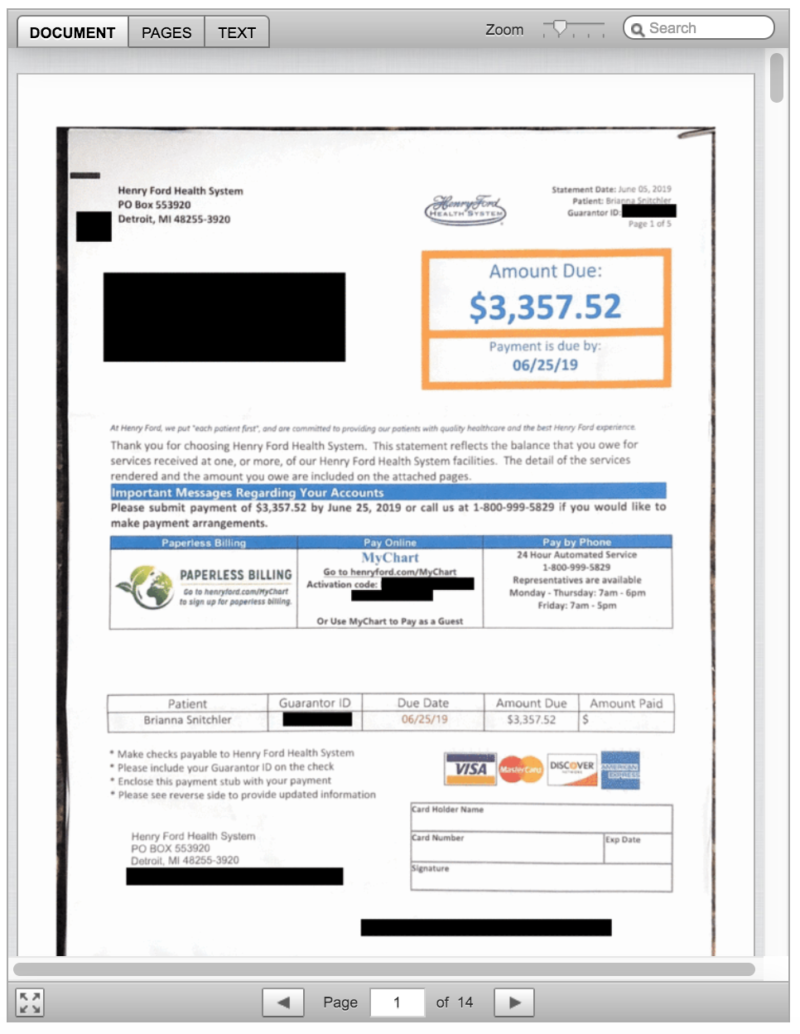

Total Bill: $3,357.52, including a $2,170 facility fee listed as “operating room services.” The balance included a biopsy, ultrasound, physician charges and lab tests.

Service Provider: Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Medical Procedure: Ultrasound-guided needle biopsy of a cyst.

What Gives: When Snitchler scheduled the biopsy, no one told her that Henry Ford Health System would also charge her a $2,170 facility fee.

Snitchler said the bill turned out to be far more than what she budgeted for. Her insurance plan from UnitedHealthcare had a high-deductible of $3,250, plus she would owe coinsurance. All told, her bills for the care she received related to the biopsy left her on the hook for $3,357.52, with her insurance paying $974.

“She shrugged it off,” Snitchler’s partner, Emi Aguilar, recalled. “But I could see that she was upset in her eyes.”

Snitchler panicked when she realized the bill threatened the couple’s financial security. Snitchler had already spent down her savings for a recent cross-country move to Austin, Texas.

In an email, Henry Ford spokesman David Olejarz said the “procedure was performed in the Interventional Radiology procedure room, where the imaging allows the biopsy to be much more precise.”

“We perform procedures in the most appropriate venue to ensure the highest standards of patient quality and safety,” Olejarz wrote.

The initial bill from Henry Ford referred to “operating room services.” The hospital later sent an itemized bill that referred to the charge for a treatment room in the radiology department. Both descriptions boil down to a facility fee, a common charge that has become controversial as hospitals search for additional streams of income, and as more patients complain they’ve been blindsided by these fees.

Hospital officials argue that medical centers need the boosted income to provide the expensive care sick patients require, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

But the way hospitals calculate facility fees is “a black box,” said Ted Doolittle, with the Office of the Healthcare Advocate for Connecticut, a state that has put a spotlight on the issue.

“It’s somewhat akin to a cover charge” at a club, said Doolittle, who previously served as deputy director of the federal Center for Program Integrity at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Hospitals in Connecticut billed more than $1 billion in facility fees in 2015 and 2016, according to state records. In 2015, Connecticut lawmakers approved a bill that forces all hospitals and medical providers to disclose facility fees upfront. Now patients in Connecticut “should never be charged a facility fee without being shown in burning scarlet letters that they are going to get charged this fee,” Doolittle said.

In Michigan, there’s no law requiring hospitals and other providers of health care services to inform patients of facility fees ahead of time.

Brianna Snitchler’s procedure took place on campus at Henry Ford’s main hospital site. When she got her bill, with its mention of “operating room services,” she was baffled. Snitchler said the room had “crazy medical equipment,” but she was still in her street clothes as a nurse numbed her cyst and she was sent home in a matter of minutes.

With Snitchler’s permission, Kaiser Health News shared her itemized bill, biopsy results and explanation of benefits with Dr. Mark Weiss, a radiologist who leads MediCrew, a company in Flint, Mich., that helps patients navigate the health system.

Weiss said it probably wasn’t medically necessary for Snitchler to go to the hospital to receive good care. “Not all surgical procedures have to be done at a surgical center,” he said, noting that biopsies often can be done in an office-based treatment center.

Resolution: Hoping for a reasonable explanation — or even the discovery of a mistake — Snitchler called her insurance company and the hospital.

A representative at Henry Ford told her on the phone that the hospital isn’t “legally required” to inform patients of fees ahead of time.

In an email, Henry Ford spokesman Olejarz apologized for that response: “We’ll use it as a teachable moment for our staff. We are committed to being transparent with our patients about what we charge.”

He pointed to an initiative launched in 2018 that helps patients anticipate out-of-pocket expenses. The program targets the most common elective radiology and gastroenterology tests that often have high price tags for patients.

Asked if Snitchler’s ultrasound-guided needle biopsy will be included in the price transparency initiative, Olejarz replied, “Can’t say at this point.”

In addition to the pilot program to inform patients of fees, Olejarz said, the hospital also plans to roll out an online cost-estimator tool.

For now, Snitchler has decided not to get the cyst removed, and she plans to try to negotiate on her bill. She has not yet paid any portion of it.

“You should always negotiate; you should always try,” Doolittle said. “Doesn’t mean it’s going to work, but it can work. People should not be shy about it.”

“We are happy to work out a flexible payment plan that best meets her needs,” Olejarz wrote when Kaiser Health News first inquired about Snitchler’s bill.

The Takeaway: When your doctor recommends an outpatient test or procedure like a biopsy, be aware that the hospital may be the most expensive place you can have it done. Ask your physician for recommendations of where else you might have the procedure, and then call each facility to try to get an estimate of the costs you’d face.

Also, be wary of places that may look like independent doctor’s offices but are owned by a hospital. These practices also can tack hefty facility fees onto your bill.

If you get a bill that seems inflated, call your hospital and insurer and try to negotiate it down.

Bill of the Month is a crowdsourced investigation by Kaiser Health News and NPR that dissects and explains medical bills. Do you have an interesting medical bill you want to share with us? Tell us about it!