There are no real evangelicals. Only imagined ones.

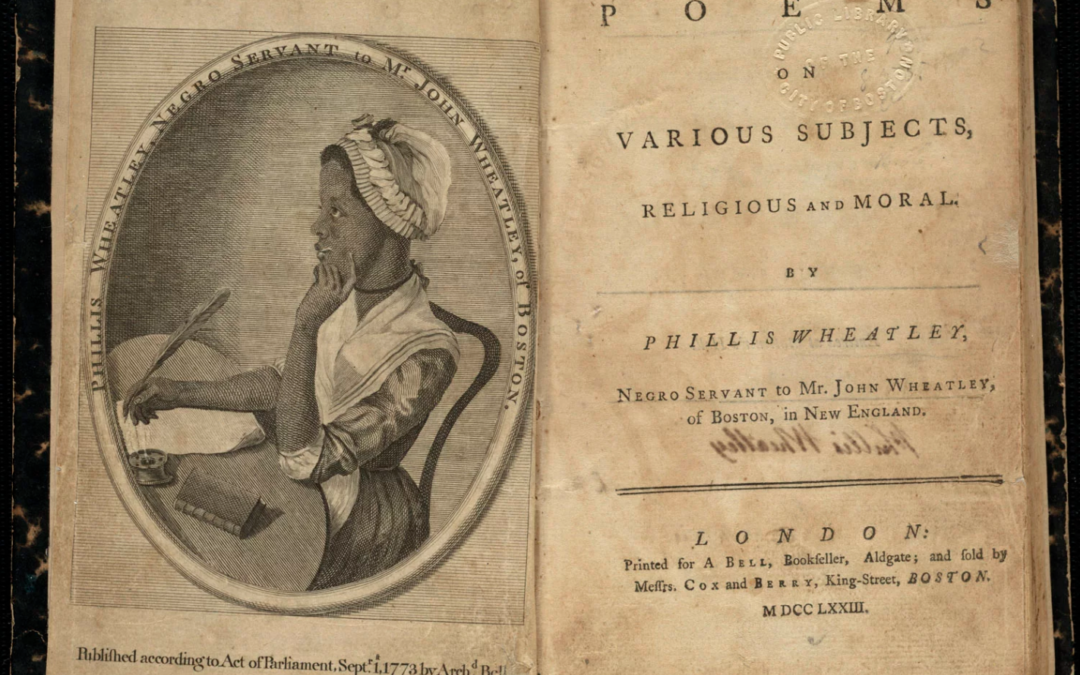

The title page of Phillis Wheatley’s 1773 book “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral.” Photo courtesy of Boston Public Library/Creative Commons

Not long ago, Baylor historian Thomas Kidd published a short post at The Gospel Coalition blog on the anniversary of Phillis Wheatley’s death. He titled his piece “Phillis Wheatley: An Evangelical and the First Published African American Female Poet,” and concluded by saying that “Evangelicals, of all people, need to remember her today.”

In response, writer Jonathan Merritt tweeted: “Calling her an evangelical is, um, a bit weird.”

“Why?” Kidd countered.

“Because you’re assigning her to a movement at a time when the movement wouldn’t have her. How are you defining evangelical?” Merritt replied. “If self-identification, did she? If denominational affiliation, was she?

“If you can’t answer the question,” Merritt concluded, “you might need to think on this some more.”

Merritt’s dig at Kidd’s expertise (Kidd has authored several books on evangelicalism) provoked other historians to join the fray, and we very quickly breached the outer limits of productive conversation.

The problem was one of definitions.

An undated portrait of Phillis Wheatley. Image photo of Creative Commons

In referring to Wheatley as an “evangelical,” Kidd, like many other historians of American religion, was using the term to describe 18th-century revivalist Christianity. Yet Kidd was also asserting that Wheatley matters especially to evangelicals today, presumably because she is one of them.

This is where things become contentious.

Does “evangelicalism” extend from Wheatley to modern day? Perhaps, if one considers evangelicalism primarily a theological tradition. But to many, evangelicalism has morphed into a politicized movement — essentially made up of white religious conservatives who vote Republican. To claim Wheatley as a progenitor of this movement is indeed rather odd.

This definitional debate has been simmering for some time, but it reached new heights after 2016 exit polls revealed that 81 percent of self-identified white evangelical voters supported Donald Trump.

Or did they?

Even before Trump secured the nomination, white evangelicals contested purported levels of evangelical support. The president of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, Russell Moore, insisted the word “evangelical” had become “almost meaningless.”

According to Moore, a big part of the problem was the media, who rely on self-identification: “Many of those who tell pollsters they are ‘evangelical’ may well be drunk right now, and haven’t been into a church since someone invited them to Vacation Bible School sometime back when Seinfeld was in first-run episodes.” When the dust settled after the election, Moore said, the time would come “to make ‘evangelical’ great again.”

During the Republican National Convention, Kidd himself echoed these sentiments in The Washington Post. He expressed frustration with “time-strapped pollsters” who “just let people tell them that they are evangelicals, without probing what that means.”

Historian Thomas Kidd. Photo courtesy of Baylor University

Somehow, an entire generation of Americans had gotten “the wrong idea about evangelicalism” — a “pop culture” definition had usurped a proper historical and theological one, resulting in a large number of “supposed evangelicals” who had no clue about “the formal definition of ‘evangelical.’”

To be a real evangelical, in other words, one needed to fit the formal theological definition — preferably, the “Bebbington quadrilateral”: biblicism, crucicentrism, conversionism and activism. Other establishment evangelicals agreed. During the 2016 election, Ed Stetzer of LifeWay Research and Leith Anderson of the National Association of Evangelicals teamed up to conduct a poll with the intention of disrupting two faulty notions: “That ‘evangelical’ means ‘white’ and that evangelicals are primarily defined by their politics.”

By defining evangelicalism by belief (and basing their model on Bebbington), they ended up with a much more diverse “evangelicalism.” Twenty-nine percent of whites end up in this category, along with 44 percent of African-Americans and 30 percent of Hispanics. (A poll by PRRI puts the percentage of evangelical Protestants who are white at only 64 percent).

It’s not hard to see how this might change our understanding of evangelicals today.

If the movement is far less white than generally assumed, it clearly cannot be primarily motivated by racism. Additionally, if evangelicalism is defined by a set of theological commitments, then one can find evangelicals the world over, and the significance of American nationalism to evangelical identity diminishes as well, for obvious reasons.

Stetzer and Anderson highlighted these racial dynamics by quoting Anthea Butler. In a speech at Fuller Seminary in 2015, the African-American scholar had complained that “Bible-believing black evangelicals” were too often ignored.

Butler, it seemed, was staking a claim on evangelicalism, and she wasn’t alone. Last August, a press release proclaimed that “evangelical women” had “hit pause” on the culture wars. Just who were these “evangelical women”? In addition to Jen Hatmaker and Rachel Held Evans, whose evangelical credentials are currently up for debate, many who signed were women of color — Brenda Salter McNeil, Latasha Morrison, Kathy Khang, Christina Edmondson.

“Evangelicals of color,” however, have an ambivalent relationship with evangelicalism. There is a reason why a recent LifeWay survey found that only 25 percent of African-Americans who ascribed to the four points of evangelical belief actually identified as evangelicals.

Anthea Butler. Courtesy photo

Black Christians have long resisted embracing the evangelical label because it is clear to them that there is more to evangelical identity than four statements of belief. In the words of Deidra Riggs, evangelicalism is a “white religious brand.”

It’s worth noting that Butler, in that same speech, went on to decry evangelicalism’s “problem of whiteness.” She called out white evangelical scholars’ inability or unwillingness to confront that problem. Bebbington’s four points, Butler asserted, are in fact culturally and racially specific.

Moreover, a recent LifeWay survey found that fewer than half of those who self-identify as evangelicals “strongly agree” with core evangelical beliefs. Many “evangelicals,” according to another LifeWay Research survey, in fact hold heretical beliefs.

When a large number of people who self-identify as evangelicals fail to ascribe to what some scholars have dictated to be the essential tenets of evangelicalism, does that mean that they are not actually evangelicals? Or does it suggest that something else has come to define evangelicalism?

Some evangelicals might see this erosion of theology and the politicization of evangelicalism as an abandonment of an illustrious heritage, but one cannot wish away the movement that evangelicalism has become.

If theology no longer defines evangelicalism, how should we conceptualize the movement?

In my own research, I examine evangelicalism as a culture of consumption, a web of interlinking personal, institutional and distribution networks. In this evangelicalism, James Dobson, Joshua Harris and the “Duck Dynasty” clan play a larger role than Jonathan Edwards or George Whitefield — or Phillis Wheatley.

An engraving of Phillis Wheatley. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Which doesn’t mean Wheatley wasn’t an evangelical. Or isn’t one, according to another definition.

All of these leave us asking: Is evangelicalism a theological category? A consumer culture? A white religious brand? A diverse, global movement?

What if the answer is “all of the above”?

Here I find it useful to borrow a page from Benedict Anderson’s scholarship and suggest that we consider evangelicalism as an imagined religious community.

There are, in fact, many evangelicalisms and each has a different center and different boundaries.

The primary question, then, isn’t which definition is “correct,” but rather which imaginings have more power to shape other people’s imaginings. When LifeWay’s stores decide you are no longer an evangelical, it matters. At least if you want to sell books. When the evangelical left claims the mantle of evangelicalism to call for an end to the culture wars, it matters rhetorically. But beyond that? When politicians claim to have the backing of evangelical voters, it matters. At least to some.

This shift in focus demands that scholars, too, examine our own positionality. How have scholars imagined evangelicalism, and to what end? Which imaginings have wielded power in the academy, and why?

Rather than seeking to impose one definition over all others, we should be more attentive to how evangelicalism has always been a dynamic, fluid movement, or series of movements imagined and maintained through networks, alliances and authority structures, each drawing and enforcing the boundaries of “evangelicalism” for varying purposes.

And we will be forced to contend with how we, too, are implicated in this imaginative process.

(Kristin Kobes Du Mez is a history professor at Calvin College. This op-ed is adapted from a presentation she gave at a joint session of the American Historical Association and the Conference on Faith and History. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily represent those of Religion News Service.)