No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

Natalie Manuel Lee, a California native, fashion stylist/influencer, is the executive producer and host of Hillsong Channel’s newest series, “Now with Natalie,” premiering on March 3. The series is a fresh, relevant, and necessary examination into the depths of the Christian millennial experience. Featuring guests such as Kelly Rowland, Tyson Chandler, and Hailey Bieber, the series focuses on purpose and identity, the blessing and curse that is social media, and staying grounded in a culture that glamorizes status over self-care. With its countercultural “it’s not what you think” approach, “Now with Natalie” is sure to set a precedent in the modern Christian narrative. Ahead of the premier, Urban Faith sat down with Natalie to find out more about her new series, what inspired the idea, and her personal journey of staying grounded in a hustle and bustle society.

WHAT INSPIRED “NOW WITH NATALIE”?

I saw a need. A plight of this generation is to glorify the one in a position instead of seeing the purpose behind that position. The idea behind the show is to dismantle counterfeit definitions of identity and purpose and to pull back the veil of false narratives that culture tends to push. What we do and what we have cannot define our worth and value. Our identity should be rooted in who we are and whose we are. I personally have wrestled with these concepts before and wanted to have authentic conversations to shed light on this.

I saw a need. A plight of this generation is to glorify the one in a position instead of seeing the purpose behind that position. The idea behind the show is to dismantle counterfeit definitions of identity and purpose and to pull back the veil of false narratives that culture tends to push. What we do and what we have cannot define our worth and value. Our identity should be rooted in who we are and whose we are. I personally have wrestled with these concepts before and wanted to have authentic conversations to shed light on this.

WHAT TOPICS DO YOU FOCUS ON IN “NOW WITH NATALIE”?

The show will focus almost exclusively on the topics of purpose and identity. Because it is such a deep and pervasive wound, the series will focus on dissecting these topics from different perspectives and experiences.

WHICH INTERVIEWS ARE YOU MOST EXCITED ABOUT?

Honestly, I am excited about all of them. Each episode serves a different purpose. You will hear about experiences ranging from the music industry, professional athletes, professionals in the area of cognitive neuroscience, and more. Each episode is enlightening and is intended to make you feel more free after watching.

WHAT IMPACT DO YOU BELIEVE SOCIAL MEDIA HAS ON SELF WORTH?

Social media can be the greatest blessing, but also the biggest curse. When misused, social media can fuel inadequacy. As humans, we tend to compare and want to compete based off what we scroll through on these highlight reels. A lot of our thoughts come from what we see and, for some, this level of comparison has peaked the epidemic of depression and anxiety. I always advocate taking periodic social media fasts, and just deleting the apps when needed.

HOW DO YOU DEFINE HAPPINESS?

As a mental perspective. When you truly know who you are and what you’re defined by, happiness will arrive. I think about happiness as joy, and the joy of the Lord is my strength. I constantly revert back to the truth of who I am, and the truth of who God is. Happiness and joy align with those truths.

WHAT IS YOUR WORK-LIFE BALANCE ROUTINE?

I start my mornings still. I give myself time in the morning, and spend time with God. The biggest lesson I have learned in the last decade is to not abort the process God is putting me through, and to keep my eyes fixed on the bigger picture. God created us each with a very specific and unique life blueprint, and He has equipped us to navigate it without looking to the left or to the right in comparison. God graces each of us to run our own unique race.

“Now with Natalie” premiers on Sunday, March 03, 2019 on the Hillsong Channel.

Tarana Burke seen on day two of Summit LA18 in Downtown Los Angeles on Saturday, Nov. 3, 2018, in Los Angeles. (Photo by Amy Harris/Invision/AP)

2018 was a whirlwind year for Tarana Burke, the founder of the “Me Too” movement. During the latter part of 2017, the long-time activist skyrocketed to fame as the phrase “Me Too” became a uniting force for victims of sexual violence. On October 15, 2017, actress Alyssa Milano sent a tweet in response to initial reports of allegations that Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein sexually assaulted numerous women. The tweet asked women who had been sexually assaulted to reply ” me too.”

That tweet made waves. Days later, millions of people used the hashtag #MeToo across social media, many of whom initially credited Milano with starting the “Me Too” movement. But Burke’s work on behalf of sexual assault survivors had been known long before Milano’s viral tweet, and it was black women who collectively spoke up to tell the actress that Burke had founded a “Me Too” movement over a decade before, during a time when there were no hashtags. Milano, who was unaware of the activist’s work, tweeted an apology. She also publicly credited Burke, and reached out to ask Burke how she could help amplify her work.

The two women traveled the media circuit together, appearing on “Meet the Press.”

Soon, organizations began to celebrate Burke in her own right. In March, she was honored at the 2018 Academy Awards. She appeared on magazine covers, including one of the six covers of TIME magazine’s “100 Most Influential People” issue, where actress Gabrielle Union, also a survivor of sexual assault, penned an essay calling Burke a “kindred spirit.”

The Bronx-born activist was the guest editor for ESSENCE magazine’s November issue, where she spoke about the future of the movement. She oversaw an edition filled with essays dedicated to black women’s right to heal after sexual violence and articles about the culture of silence around the sexual assault of black women and girls.

In an interview, the mother of “Me Too” said she never imagined she’d be in such a position of visibility. But, she didn’t feel like a hero. Instead, she told the magazine, she felt “dutiful,” and much of that duty was to ensure that black women weren’t shut out of the “Me Too” movement. While Milano’s intent wasn’t to steal Burke’s work, her celebrity status did catapult the conversation around sexual assault into the media, particularly in a way that resonated with white women. And it pained Burke to see black women erased from the narrative.

“The world responds to the vulnerability of white women,” she told ESSENCE. “Our narrative has never been centered in mainstream media. Our stories don’t get told and, as a result, it makes us feel not as valuable.”

In November, she also spoke about her duty to re-center the mission of “Me Too.” During her first TED talk, a speech dedicated to survivors and activists, she described how the past year had been an emotional roller coaster.

“This movement is constantly being called a watershed moment. Even a reckoning. But I wake up some days feeling that all evidence points to the contrary,” Burke told the audience.

A year later, “Me Too” was described as a “culture shock.” Harvey Weinstein was indicted. Bill Cosby was finally sentenced to prison in September for allegations of rape which were reignited after comedian Hannibal Buress mocked Cosby during a stand-up routine in 2014.

Despite the success of “Me Too,” Burke said the movement had become unrecognizable at times, as people, including the media, presented and interpreted “Me Too” as a vindictive plot against men, instead of as a voice of support for survivors. Her speech was a call to refocus the energy of the movement on survivors of sexual assault.

She also called to dismantle the building blocks of sexual violence: power and privilege.

Now, in 2019, it seems like her two key missions of the “Me Too” movement: visibility for black female survivors of sexual violence and the dismantling of power and privilege will finally converge.

Burke appeared in Lifetime’s six-hour docuseries, “Surviving R. Kelly.”

The three-night special is a deep dive into the background of singer R. Kelly and the decades of sexual assault allegations against him, weaving testimonies of his alleged victims — all black and brown women — with interviews from their friends, parents and teachers. Burke is part of a team of experts, including activists, journalists, and cultural critics, assembled to shed light on why the singer’s history of abuse — while heavily reported — has been ignored.

Burke has devoted her career to working at the intersection of racial justice and sexual violence, and she spent significant time in Selma laying the groundwork that would later evolve into the “Me Too” movement.

In October, days before the one-year anniversary of the tweet that launched “Me Too” on social media, Burke returned to Alabama to talk about her roots as an activist.

For Burke, that appearance was indeed a homecoming, as she stood before her elders. This included Rose Sanders, her mentor during her formative years in Selma, who waved at her from the third row of an auditorium in UAB’s Alys Stephens Center.

It was a semi-full circle moment. In March, Sanders, who made history in 1973 as the state’s first African American female judge, proudly told a room full of people in the Dallas County courthouse during the annual Bridge Crossing Jubilee that Burke started the “Me Too” movement in Selma.

As Burke took the stage to cheers and a standing ovation, she paid homage to her elders.

“I know I have my family from Selma here,” she said, lovingly holding out her hands. “You all are part of my story.”

“People keep thanking me for coming to Birmingham,” said Burke, smiling widely as the audience simmered down. “That’s because they don’t know I have ties to Alabama. I relish the opportunity to come here.”

For close to an hour, Burke talked about her childhood, her early years in Selma, and the life-changing moment that would lead her to start the movement known as “Me Too.”

THE EARLY YEARS

Burke was groomed to be an activist as a child.

“I had a normal family,” Burke told the audience. “Except for I had a grandfather that was a Garveyite.” Her grandfather, a close follower of the teachings of Marcus Garvey, made sure she was well versed in the readings of black liberation. On car rides, they would listen to cassette tapes of John Henrik Clarke, a native of Union Springs, Al. who was a scholar and pioneer in the field of Africana studies.

“You can read that Bible, but make sure you have your history right along with that,” she said he’d tell her.

Burke’s mother, while she never referred to herself as a feminist, surrounded Burke with the works of Audre Lorde and Patricia Hill Collins.

“I was wrapped in Black feminist literature growing up.”

Burke was discovered at age 14 by the 21st Century Youth Leadership Movement, an organization founded by Rose Sanders in 1985 to educate young people about voting rights and the political process. And it was through that organization that Burke says she learned about the impact youth could have.

“That was the first time an adult had said to me, ‘you have power now.’ ”

Through her work with the 21st Century Youth Leadership Movement, she became an activist. One of the first cases she worked on would be the case of the Central Park Five, a group of black and latino teenagers from Harlem who were wrongly convicted of assaulting and raping a white woman in Central Park in 1989. Their sentences would be overturned decades later.

“It’s so funny how we talk about due process in the White House now,” referencing President Donald Trump, who in the 1980s took out full page ads in four of the city’s newspapers, calling for the return of the death penalty, but in 2018 demanded due process for former White House staff secretary Rob Porter and speechwriter David Sorensen after allegations of domestic abuse, and Brett Kavanaugh, his nominee to the Supreme Court who was faced with allegations of sexual assault.

HER JOURNEY TO ALABAMA

Burke traveled to Alabama for college where she continued to organize, starting at Alabama State before transferring to Auburn University.

“Your college campus is practice for the real world,” she told the audience.

After graduation, Burke went to work in Selma, where an experience changed the trajectory of her life.

While working as a camp counselor for the 21st Century Youth Leadership Movement, she met a girl she would describe to the audience as “Heaven.”

As a counselor, she had started workshops where young girls could speak openly and reveal stories about sexual violence and assault.

One day, Heaven made a beeline for her. Immediately, Burke said, she knew something was wrong. At first she avoided Heaven because she didn’t feel equipped to provide guidance for what she knew would be devastating news.

“I thought to myself ‘I’m not a counselor,’ said Burke. “But in my heart, I thought, that happened to me too.”

But in that moment, Burke said as she lowered her voice, those words didn’t seem like enough. But later, she realized that phrase was the one thing she needed to tell Heaven.

Burke told the audience she spent years afterwards feeling guilty. Over and over again, she’d ask “what difference does ‘me too’ make?”

Turns out, the phrase would make a lot of difference.

JUST BE, INC. : THE BEGINNING OF ME TOO

In Selma, Burke started Just Be, Inc., an organization focused on the health and well being of young girls of color. As the organization grew quickly, Burke noticed a pattern — when the girls gathered together, stories started spilling out. And when the girls shared their stories, Burke said, she’d always think about her encounter with Heaven.

As her work in a Selma junior high school continued, the stories from young girls kept coming and Burke started to notice a common thread. The girls told their stories as if they were normal experiences, not revealing painful secrets. None of the girls knew they were describing acts of sexual violence.

The tipping point came when Burke saw a 12- year-old student waiting for her “boyfriend” after school — a boyfriend who was 21 years old. To make matters worse, it was a man Burke already knew. He had been dating one of the girls at a local high school the year before.

“How do you tell a 7th grade girl that this is not a relationship, this is a crime?” said Burke.

She realized it was up to her to change and translate that wording into a conversation that young girls could understand.

“So we had to figure out how to simplify that language.”

DESIGNING THE TOOLS TO TALK ABOUT SEXUAL ASSAULT

Burke had previously read about how to teach young people to talk about sexual assault, but recognized no one was relaying those messages to girls.

“Nobody was speaking healing into our community,” said Burke. “How can we heal something that we can’t name?”

She and her team started off by teaching the girls ways to recognize sexual violence.

Burke started going into the community to find resources, starting with another junior high school.

She also went into a local rape crisis center, located next to a homeless shelter. But, that environment, said Burke, wasn’t a comfortable or safe space for young girls. In order to get to the crisis center, girls would have to walk past groups of men huddled outside of the center who would often yell catcalls.

Burke says that walk into the rape crisis center was the turning point.

“That day was the nugget,” said Burke. “Adult women don’t report sexual violence. Do you think these children would go through that?”

“THE BIRTH OF ‘ME TOO’ “

Looking into the audience, Burke reflected on guidance from her mentors in Selma

“An elder once told me: you have to take what you have to get what you need.”

With that advice, she started a Myspace page for her project to gain visibility. Her goal was simple: she wanted people to see the resources she’d compiled and the work she was doing.

Soon, Burke says, people started reaching out to thank her. She knew the next step was to distribute the resources to even more people.

“I remember sitting with my two friends in my living room and wondering ‘how are we going to make this work?’ ”

The method they came up with was simple — she and her friends packed the resources into glossy folders and shipped them out around the country.

Soon after, Burke left Selma to move to Philly.

THE AFTERNOON OF 2017

“I always intended for ‘Me Too’ to be a movement for survivors,” said Burke.

But for years, the challenge was getting people in the room to have the conversation about sexual assault.

“Filling up a room like this would be impossible,” said Burke, motioning to people sitting in the Alys Stephens Center.

She said she would have to reach out to churches to ask them to speak. She describes the tweet Milano sent in 2017 as a “lightning bolt” that gave life to the healing she had been trying to bring to young girls for more than two decades.

Alyssa Milano’s “me too” tweet reached millions on Twitter in 24 hours. On Facebook, there were more than 12 million comments, posts and reactions.

But she says she wasn’t upset that it took a viral hashtag to catapult her cause.

“What I care about is getting the room full now. We are just not comfortable being uncomfortable,” said Burke. “This is hard, but we have the ability to get this right.”

And getting it right, says Burke, means believing survivors and not blaming them for being victims of sexual assault.

“If we woke up and found out that 12 million people all had a disease, we wouldn’t ask ‘well, who were they touching?'” Burke remarked, a statement met with uproarious applause.

The focus, she says, should be on what happened and how to stop it.

But people have misconstrued the message of the movement to be about taking down powerful men.

Burke told the audience she was in the room when Dr. Christine Blasey Ford testified before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee that she was allegedly assaulted by Kavanaugh. She says powerful men like Kavanaugh were the “epitome” of unchecked power and privilege.

“This is the first time that we’ve seen any modicum of accountability in our lifetime,” said Burke. “This is not about crime and punishment. It’s about harm and harm reductions.”

But Burke knows why the “takedown” narrative has caught on: “if you say something over and over again, people will start to believe it.”

And now, says Burke, it’s time take back the focus in order reach communities of survivors who desperately need the help of the movement.

“Outside of Black women, it astonishes me that we have no conversations about native women and sexual violence.”

“ME TOO” IN ALABAMA

Rose Sanders had to leave the Alys Stephens center early, so she didn’t get to say a formal goodbye to the activist she once mentored. But she beamed with pride as she talked about Burke, the young student she took under her wing.

“It’s awesome. She’s true to her cause. And I’m glad she’s pushing 21st Century (Leaders). And I’m hoping she’ll do it more.”

Sanders says there’s an even greater need for community focused leadership development now, and wished there were more young people involved the struggle against sexual abuse.

“When I started (the organization) it was in 1985, 20 years after the civil rights movement. It became clear to me that very few young people even knew about the movement,” said Sanders. So we were fortunate enough to get people like John Lewis, Rosa Parks and Jesse Jackson to come to our camps.”

But Sanders has plans to bridge the communication gap. She says she wants to build on Burke’s work, growing the “me too” movement into the “we too” movement.

“It’s not just about the survivors of the actual physical damage. It’s also about a mother who may not have been sexually abused, but has to suffer through (her child’s) abuse. It’s got to be “we too.”

This year, she plans to have workshops to educate attendees of the Bridge Crossing Jubilee about sexual assault, and has her vision set on bringing back Burke to speak on at least one of the panels.

“The people who are the actual victims of assault suffer the most damage, but so does everybody that’s connected to that child or that woman that’s been sexually violated,” said Sanders. “We too are also hurting and it’s going to take all of us to resolve it.”

And as Burke closed her speech, she also acknowledged that the movement was bigger than her, and challenged the room to take action after the lecture and challenge institutions to protect survivors and prevent sexual assault.

“I’m a 45-year-old black woman. It’s not enough to celebrate me if you’re not going to commit to ending sexual violence and the movement I stand for.” said Burke.

“This is really about people being able to walk through life with their dignity intact.”

Published through the AP Member Exchange

Supporters of opposition presidential candidate Felix Tshisekedi celebrate at his headquarters in Kinshasa, Thursday Jan. 10, 2019. Supporters of Tshisekedi took to the streets of Congo’s capital, Kinshasa, Thursday morning to celebrate his win in the presidential election, that was announced by the electoral commission. (AP Photo/Jerome Delay)

Congo is on the brink of its first peaceful, democratic transfer of power since independence in 1960 after the Constitutional Court on Sunday confirmed the presidential election victory of Felix Tshisekedi, although questions remain about the result.

Tshisekedi, son of the late, charismatic opposition leader Etienne, is to be inaugurated on Tuesday.

Congo’s 80 million people did not appear to heed runner-up Martin Fayulu’s call for non-violent protests, and African neighbors began offering congratulations.

Shortly after the pre-dawn court declaration, opposition leader Tshisekedi said the court’s decision to reject claims of electoral fraud and declare him president was a victory for the entire country.

“It is Congo that won,” Tshisekedi said, speaking to supporters. “The Congo that we are going to form will not be a Congo of division, hatred or tribalism. It will be a reconciled Congo, a strong Congo that will be focused on development, peace and security.”

Supporters of his UDPS party celebrated in the streets of Kinshasa.

The largely untested Tshisekedi faces a government dominated by Kabila’s ruling party, which won a majority in legislative and provincial elections. The new National Assembly will be installed on Jan. 26.

However, Tshisekedi’s victory was rejected by rival opposition candidate Fayulu, who declared that he is Congo’s “only legitimate president” and called for the Congolese people to peacefully protest against a “constitutional coup d’etat.” If Fayulu succeeds in launching widespread protests it could keep the country in a political crisis that has simmered since the Dec. 30 elections.

The court turned away Fayulu’s request for a recount, affirming Tshisekedi won with more than 7 million votes, or 38 percent, and Fayulu received 34 percent.

The court said Fayulu offered no proof to back his assertions that he had won easily based on leaked data attributed the electoral commission. It also called unfounded another challenge that objected to the commission’s last-minute decision to bar some 1 million voters over a deadly Ebola virus outbreak.

Outside the court, Fayulu and his supporters have alleged an extraordinary backroom deal by outgoing President Joseph Kabila to rig the vote in favor of Tshisekedi when the ruling party’s candidate did poorly.

“It’s a secret for no one inside or outside of our country that you have elected me president,” with 60 percent of the votes, Fayulu said. He urged the Congolese people and the international community to not recognize Tshisekedi as president.

Congo’s government called Fayulu’s statements “a shame.”

“We consider it an irresponsible statement that is highly politically immature,” spokesman Lambert Mende told The Associated Press.

Many worried that the court’s rejection of Fayulu’s appeal could lead to more instability in a nation that already suffers from rebels, communal violence and the Ebola outbreak.

“It might produce some demonstrations, but it won’t be as intense as it was in 2017 and 2018,” when Congolese pushed for Kabila to step aside during two years of election delays, said Andrew Edward Tchie, research fellow at the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

The African Union said it had “postponed” its urgent mission to Congo planned for Monday after it noted “serious doubts” about the vote and made an unprecedented request for Congo to delay the final results.

Some neighbors, notably Rwanda, worried about violence spilling across borders from Congo, a country rich in the minerals key to smartphones around the world.

The AU statement notably did not name or congratulate Tshisekedi, merely taking note of the court’s decision. It called “all concerned to work for the preservation of peace and stability and the promotion of national harmony.”

A number of African leaders congratulated Tshisekedi, including the presidents of South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania and Burundi. The 16-nation Southern African Development Community, after wavering in recent days with support for a recount, called on all Congolese to accept the vote’s outcome.

Tanzanian President John Magufuli, in a post on Twitter, said that “I beseech you to maintain peace.”

Cheryl Thompson, Ryerson University

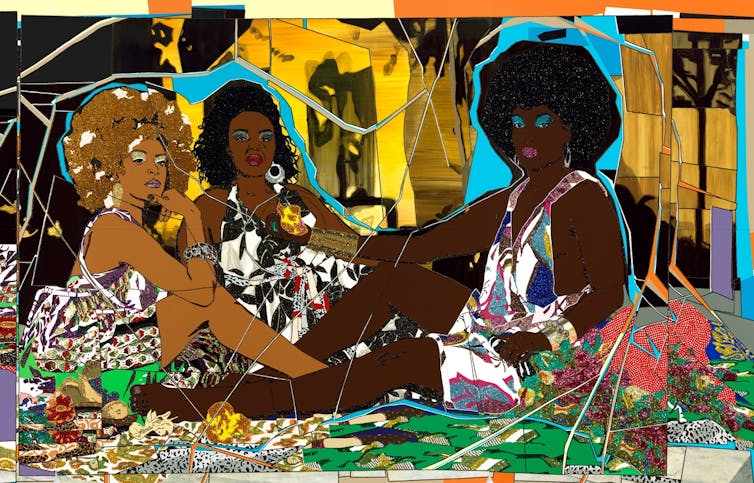

Renowned visual artist Mickalene Thomas has taken over the fifth-floor gallery space of the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) with her show “Femmes Noires.” Working with curator Julie Crooks, it is the first time the Brooklyn-based artist has staged an exhibition in Canada — and it is only the second time the AGO has exhibited the work of a Black woman artist.

Thomas’s exhibit is a powerful and extraordinary contemplation on the intersections of being both Black and a woman. Thomas takes inspiration from multiple art forms, movements, and histories, like Impressionism, and focuses on issues such as race, representation, sexuality, and Black celebrity culture.

As a Black woman, it is the first time I have ever walked the floors of the AGO and have seen myself reflected back at me. However, something for Canadians like myself to note is that Thomas’s visioning of Black womanhood is from an American point of view.

(The last solo exhibition by a Black woman at the AGO took place in 2010 — “This You Call Civilization?” featuring the work of Kenyan-born, New York-based Wangechi Mutu.)

Blackness in Canada has often been framed through an African-American lens. This representation (or lack of) is an issue I fully explore in my book, Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture.

For example, one of the reasons why Black beauty culture has not received much attention in Canada until now is because the task of locating Black voices in the Canadian historical record has been and remains a difficult challenge. Across the border, there are archival collections dedicated to African Americans, such as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City, but we don’t have anything like this in Canada.

When I started researching Black beauty in Canada, most people were shocked there was enough material for me to write about in a book. The assumption was that the topic would have to focus squarely on African-American women.

For decades, Canadian cultural institutions have consumed African-American desires and fantasies as stand-ins for Black Canada. As a result, Black Canadian representations in popular culture have been rendered invisible.

Throughout the 20th century, cultural and economic practices were co-produced through the circulation of “African-Americanness” through media. From African-American TV shows in the 1970s, films in the 1980s and beyond, Canadians probably know more about the African-American experience than they do about Black Canadians because of media culture.

Canada’s media culture has participated in the creation of identities that privileged African-American images, products, and ideologies. These identities originally crossed the U.S./Canada border as desires and fantasies represented in advertising and, later, television and film, and today, art.

When Trey Anthony’s ’da Kink in My Hair TV series appeared from 2007-09 (based on the play of the same name), it was the first comedy series created by and starring Black women on Canadian national television. The broadcast of ’da Kink in My Hair happened nearly 40 years after Julia (1968–71) in which Diahann Carroll became the first African American woman to star on a U.S. sitcom in a non-stereotypical role. The representation gap between African American women and Black women in Canada spans decades.

To make up for some of this historical invisibility, this month and throughout the winter, the AGO’s “In the Living Room” series will feature Black Canadian women engaging with Thomas’s art and discussing their experiences.

Each talk will be set in the Femme Noires’ living room space, which is modeled after Thomas’s childhood home growing up in New Jersey. The patchwork chairs and books from African-American women authors become the art installation. Visitors are called to engage intimately with the paintings, installations, and videos on the walls but also the productive space, the living room, that birthed Thomas’s art in the first place.

The first discussion in the series, “The Dis/Appearing Black Body,” will feature portrait photographer Jorian Charlton and Shantel Miller, an artist-in-resident at Nia Centre for the Arts in Toronto, to discuss Black bodies, power, and the gaze.

While I can say much about the differences between Black Canadian experiences and African-American ones, there are universal Black beauty experiences that unite all women of African descent. For example, one of these experiences is the caring for and discussions around Black hair. Some of these public conversations are hurtful to many Black women.

The New York-based online platform, Hello Beautiful, which targets their articles toward Black women, recently asked why Black women should have to defend wigs and weaves more than other women. The article explores why Black women are constantly asked to defend being women and all the things we do, like our hair, to feel beautiful.

On the one hand, our hair is connected to many painful childhood memories of being teased by other children (and sometimes adults) about our various braided hairstyles. On the other hand, natural hairstyles like Afros, dreadlocks or cornrows (tightly braided rows of hair) might denote a Black woman’s politics, but they can also be just a hairstyle or her preference, with no political meaning whatsoever.

Black women who wear hair weaves or wigs can also be the subject of ridicule. In 2017, former Fox News host Bill O’Reilly was forced to apologize to California Congresswoman Maxine Waters, who is African American, when he made disparaging comments about her hair on the cable news program, Fox and Friends. He described her straightened hair as a “James Brown wig.”

Black hair is constantly debated, politicized and misrepresented in media, art, and popular culture. A simple decision about wearing it natural or straightened could result in punitive action — not in America, but right here in Canada. This was the case for a waitress-in-training who lost her job at Jack Astor’s because she wore her hair in a bun, and not “down” as required by female wait staff while working at the restaurant.

Black hair stories resonate with Black Canadian women, too. But resonance is not the same as representation.

Why have Black Canadian women artists not been given the same opportunity to exhibit their work as solo artists in Canada? This question about Black Canadian artists and how Black art has been represented and circulated has become prominent in Canadian media lately.

In an article for Canadian Art, Connor Garel wondered why no Black Canadian woman has ever had a major solo exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO).

Curator Ashley McKenzie-Barnes wrote an article for the Toronto Star, and argued that Canadian art fairs, public art installations, festivals, major institutions, and galleries need to make space for Black Canadian artists. She is right. We’re doing the work — now we need the space to get recognized for it.![]()

Cheryl Thompson, Assistant Professor, Ryerson University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

I’ve read about moms who have known since their kids were toddlers that they wanted to homeschool. That wasn’t the case for my family. Until recently, both my two boys have always been in public schools. Our journey to homeschooling came by way of a lot of personal issues that we couldn’t have predicted. Honestly, I never considered it before now. But here I am and, actually, I’m starting to wonder why I waited so long. I wanted to do this column to provide resources and encouragement to others who find themselves in a similar situation. I’ll be writing a new post each month (or more if time permits) with an update on how we’re doing, adding any new resources I’ve uncovered, and sharing tidbits about homeschooling that I’m learning along the way.

— Shari

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.