Seminaries partner with prisons to offer inmates new life as ministers

Jamie Dew, dean of the college at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, teaches a theology class to inmates at Nash Correctional Institution in Nashville, N.C. RNS photo by Sam Morris

Inside a squat cinderblock building on the grounds of Nash Correctional Institution, 24 inmates are hunched over white plastic tables listening to Professor James Dew explain how God is omnipotent and omniscient.

More than half of the men listening are serving life sentences for murder, armed robbery and other offenses. The rest have at least 12 years left to serve.

But Dew is not preaching to his audience as he paces the room posing questions about whether God can sin (No) or know people’s emotions (there’s disagreement, but most Christians say yes). He is teaching theology to prospective ministers.

The prisoners jotting notes, calling up documents on closed-circuit laptops or asking Dew questions of their own are earning four-year bachelor’s degrees in pastoral ministry from the College at Southeastern, the undergraduate school of Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in nearby Wake Forest.

Dew’s class is part of a new niche in prison education: training inmates to become “field ministers” who serve as counselors for other inmates, lead prayers, assist prison chaplains and generally serve as a calming influence in prison yards.

Many of Dew’s students get up at 5 a.m. for devotionals, though it is not required. They attend lectures from 8:15 to 11:15, Monday through Thursday. There’s study hall in the afternoon and group study in the evenings. Each inmate gets a laptop with access to a limited online resource library.

Decades of research show that inmates who get an education have a far lower incidence of repeating criminal behavior, but of the 1.5 million people in U.S. prisons, only a tiny percentage can afford a college degree while behind bars.

Evangelical seminaries, led by Southern Baptist-affiliated schools, are increasingly stepping into the gap, raising money to offer inmates free, on-site college degrees in exchange for their labor once they graduate. Inmates in 15 states can now apply for such programs, and 10 more seminaries have programs in the planning stages, according to the Global Prison Seminaries Foundation, which helps set them up.

The degree awarded is different from state to state. In North Carolina, it’s a Bachelor of Arts in pastoral ministry; in Texas, a Bachelor of Science in biblical studies; and in South Carolina, an Associate of Arts degree.

Inmates at Nash Correctional Institution in Nashville, N.C., are able to pursue a bachelor’s degree in pastoral ministry. RNS photo by Sam Morris

Game Plan for Life, a foundation started by Hall of Fame NFL coach and NASCAR team owner Joe Gibbs, funds North Carolina’s effort, which costs nearly $300,000 a year. The Heart of Texas Foundation funds a similar program in Texas, which this year had a budget of $260,000.

More money goes to build up the educational infrastructure at prisons before classes can begin. Here at the Nash Correctional Institution, Southeastern Seminary received two grants to fund a library, and Game Plan for Life is now planning a $500,000 classroom building on prison grounds.

“We bring the academics, the state brings the legal clearance and helps us navigate the red tape, Game Plan for Life brings the financial component,” said Dew, the dean of Southeastern College and one of the half-dozen professors who spends a morning each week teaching at the prison. “It’s a three-way partnership.”

Since the program started two years ago, hundreds of North Carolina’s 36,635 prison inmates have applied to take the course of study and 53 have been admitted. Applicants must be felons serving minimum 15-year sentences with a high school diploma or GED and a clean disciplinary record for at least a year.

“Before we came here a lot of us were living in despair — no hope,” said James Benoy, who has been taking classes for the past 18 months. “It’s transformed us. We have a purpose, a direction and a mission in life.”

Most of the participants here were reared as Baptists or in various Pentecostal denominations. But by law, the programs must admit inmates of all faiths. At Nash Correctional, there are a few Catholics, a Muslim and one Rastafarian.

Still, the doctrine taught here is consistent with what Southern Baptists believe — that the Bible is divine revelation and inerrant.

That raises questions for some scholars about whether the programs privilege one set of religious beliefs over others. In general, prisons must provide equally for all inmates, regardless of their faith, or lack of it.

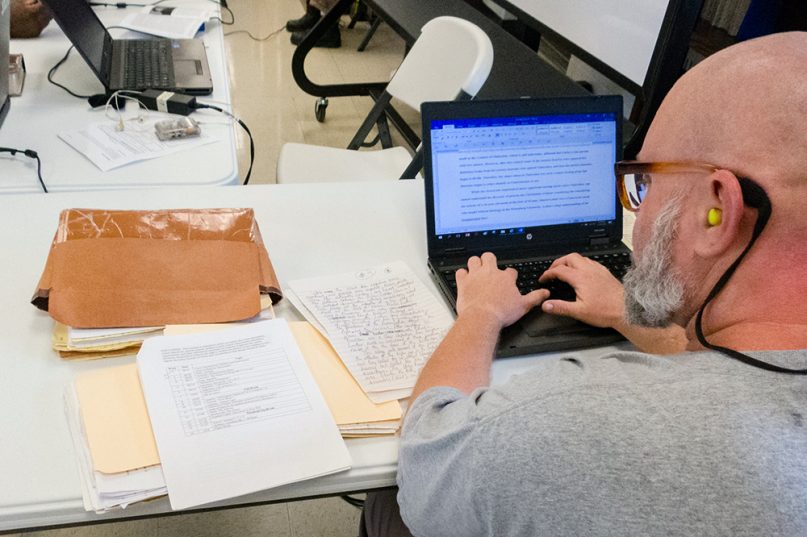

An inmate at Nash Correctional Institution works on material for a theology class in Nashville, N.C. RNS photo by Sam Morris

There are other concerns, too. “From my perspective, the larger issue is to what extent American prison systems are outsourcing rehabilitation to religious volunteers,” said Michael Hallett, a professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of North Florida who has written extensively about seminary prison programs.

Hallett questions just how voluntary these charitably funded programs are, since in most cases there are no secular alternatives.

“If the only game in town is a religious education program that’s going to result in you being in an easier prison while you’re doing life in prison, how authentic is the profession of faith?” he asks.

While inmates at most prisons can take correspondence courses from universities, as well as train to become plumbers, electricians or computer technicians, the cost of a bachelor’s degree makes it unattainable for most. (One exception is New York State’s Bard Prison Initiative.)

In 1994, Congress eliminated Pell grants for people serving in prison. (The Obama administration began a pilot program to resume prisoner access to Pell grants, but it faces an uncertain future.)

When the Pell grants were ended, the warden at the Louisiana State Penitentiary feared his famously fractious prison, known as Angola, would erupt in violence. He reached out to New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary to explore the possibility of offering some kind of education to his charges.

By 1995, the New Orleans seminary began offering a few classes at the prison, which is America’s largest, housing some 6,300 inmates.

Since then, 312 Angola inmates have earned B.A. degrees in Christian ministry, and 80 of them are still working as field ministers in prisons across the state. The New Orleans seminary now runs identical prison programs in Florida, Georgia and Mississippi.

In 2011, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas, began offering a Bachelor of Science in biblical studies at Darrington Unit, a maximum security prison 30 miles south of Houston.

Calvin College, Appalachian Bible College, Trinity International University, North Park University and Columbia International University — all evangelical schools — have since started their own prison seminary programs.

For many seminary leaders, teaching prisoners is simply what their Christian faith demands.

“We tell people that as an institution it’s our mission to train people to go into the darkest places in the world and to be the light of Christ,” said Dew. “Most of our faculty see it for what it is — an opportunity to fulfill our mission.”

For prison administrators, the programs are attractive for another reason: They cost the state little or nothing. The prisons are normally responsible only for conducting initial screenings, interviewing applicants and providing transportation to the unit where the learning takes place. For that they get a host of tangible benefits: fewer disciplinary infractions and free labor in grief counseling and conflict resolution from program graduates.

“It changes the culture of the prison from within,” said Burl Cain, a former warden at Angola who now heads the Global Prison Seminaries Foundation. “They calm it down. You get rid of gangs. It really makes a difference.”

On their way out of their Biblical Hebrew class on a recent Thursday, the inmates at Nash Correctional lined up to shake the instructor’s hand, a weekly routine the students initiated.

“It’s making me a better person,” said 41-year-old Marquis McKenzie, who was sentenced to life for first-degree murder. “I think differently now. I read well, speak well, write well and think well.”

Professors said the students’ abilities vary, but they noted the inmates were all hardworking and tenacious.

Indeed, many inmates said they feel they’ve been offered a real opportunity to make something of their lives. And they said they look forward to imparting some of the wisdom they’ve acquired to younger inmates just coming in.

“Being in prison can be so dehumanizing,” said Bryce Williams, 36, who is serving an 18-year sentence for second-degree murder. “You don’t have any autonomy. That’s stripped away. So you start to think: ‘How can I effect change?’ This program has opened up doors. It affords you an opportunity to be human.”