Cory Booker could be a candidate for the ‘religious left’

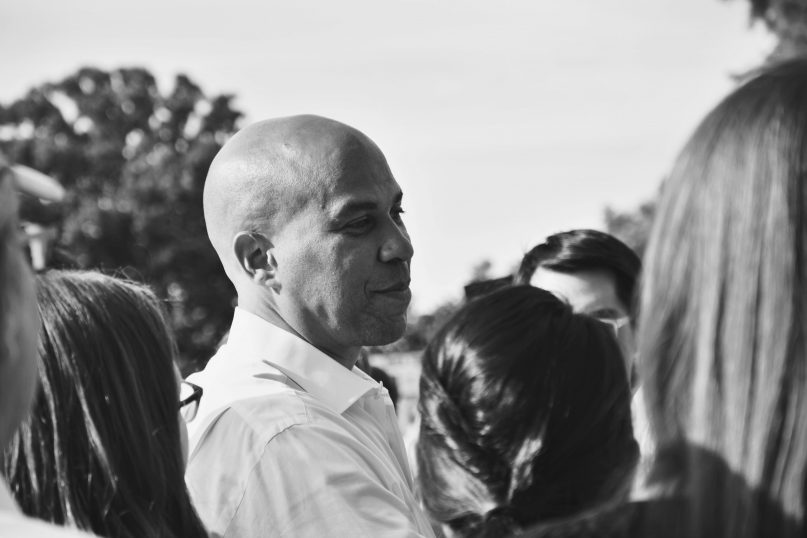

Cory Booker meets with demonstrators at a protest in Washington, D.C., on June 28, 2017. RNS photo by Jack Jenkins

Questions about religion can paralyze some politicians, but not Cory Booker.

If anything, the topic seems to relax him. Sitting in his spacious but spartan office on Capitol Hill in early October, the senator propped his sneakered feet up on his desk and waxed poetic about spiritual matters, bouncing between discussions of Jesus’ disciples, housing policy and his own religious practices.

“When I get up in the morning, I meditate,” the New Jersey Democrat said, a practice he has often linked to his spiritual health. He paused for a moment, then quickly corrected himself: “Actually, I pray on my knees, and then I meditate.”

Booker’s comfort with his faith is unusual for Democrats in Washington, but it’s standard fare for the 49-year-old former mayor of Newark and has even become a mainstay of his blossoming political persona: Even the hyperbole-averse Associated Press recently compared him to an “evangelical minister” after Booker addressed a group of Democrats in Iowa.

AP had good cause: The decidedly progressive speech, which many speculated was a warmup for a 2020 presidential run, was peppered with talk about “faithfulness” and “grace.” Booker closed by citing Amos 5:24 (“But let justice roll on like a river, righteousness like a never-failing stream!”) before shouting “Amen!” over the roaring crowd.

Asked about his tendency to fuse the political with the spiritual, Booker shrugged.

“I don’t know how many speeches of mine you can listen to and not have me bring up faith,” he said. He noted he had just come from a Senate Judiciary Committee meeting where he had lifted a line from his stump speech: “Before you tell me about your religion, first show it to me in how you treat other people.”

The sentiment, along with a message of unity that he brands as a “new civic gospel,” is generating buzz among Democrats. But Booker’s brand of public religiosity is especially attractive to an oft-forgotten but increasingly powerful group: the amorphous subset of religious Americans sometimes known as the religious left.

If he does run for president, as many expect, Booker may be one of the first Democratic candidates in decades to actively cultivate support from religious progressives.

A favorite of lefty faithful

Raised in an African Methodist Episcopal church and now a member of a National Baptist church in Newark, Booker has become a fixture at left-leaning religious gatherings as far back as 2014, when he showed up at a summit hosted by Sojourners, a Christian social justice organization. He “basically preached a sermon at the opening reception,” tweeted one organizer of the event.

In 2017, Booker attended a protest outside the U.S. Capitol hosted by the Rev. William Barber II, a prominent religious progressive who was there to denounce the Republican-led effort to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act. Earlier this year, Booker spoke at the Festival of Homiletics, a preaching conference attended by primarily white, liberal mainline clergy.

His appearance at these events has often resulted in standing ovations, and near endorsements.

“I don’t hope to move to New Jersey, but I do hope to vote for you someday, if you catch my drift,” the Rev. David Howell, the Presbyterian founder of the Festival of Homiletics, said while introducing Booker in May.

Booker claims that his faith is not partisan: He said religion is a way to reach across the aisle, and Republican Sen. John Thune is reportedly a member of his Bible study (along with New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, another potential Democratic presidential hopeful). But if Booker is unapologetic about his faith, he’s also unapologetic about the potential political effect of his God-talk.

“I think Democrats make the mistake often of ceding that territory to Republicans of faith,” Booker said.

Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., in his Washington office on Oct. 17, 2018. RNS photo by Jack Jenkins

Eric Gregory, who studied with Booker at Oxford University as a Rhodes scholar and at Yale, said the senator’s fascination with faith is nothing new.

“He certainly has always been religiously musical,” said Gregory, now a professor of religion and chair of the humanities council at Princeton University.

Booker’s fluency with faith isn’t restricted to Christianity. His Facebook feed includes mentions of the Buddha, he referenced the Hindu god Shiva in a recent interview, and at Oxford in the 1990s he chaired the L’Chaim Society.

“He was always curious about diving deeply into different religious traditions and trying to understand them but also find wisdom within them,” said Gregory.

Still, Booker roots his personal faith in Christianity, particularly the black church tradition in which he was reared.

“I will talk about my faith, and I also talk about other faiths I study,” Booker told Religion News Service, sitting beneath an image of Mahatma Gandhi, one of the few adornments on his office walls. “I’ve studied Torah for years. Hinduism I’ve studied a lot. Islam, I’ve studied some, and I’ve been enriched by my study. But, for me, the values of my life are guided by my belief in the Bible and in Jesus.”

It’s an approach to religion — multifaith, LGBTQ-inclusive, liberation theology-influenced and social-justice focused — that jibes perfectly with the makeup of the liberal coalition.

“The life of Jesus is very impactful to me and very important to me,” he said. “He lived a life committed to dealing with issues of the poor and the sick. The folks that other folks disregard, disrespect or often oppress. He lived this life of radical love that is a standard that I fail to reach every single day, but that really motivates me in what I do.”

But Booker insisted his connection with religious left leaders such as Barber, who spoke at the 2016 Democratic National Convention, has less to do with political angling and more to do with a natural overlap of shared values.

“I find kinship with people I find inspiration from — people I would love to be more like,” he said. “Rev. Barber is powerful. To me, his charisma speaks, in an instructive way, towards my heart and my being. He is somebody who believes that being poor is not a sin or that poverty is a sin.”

Riding progressive religious power

Progressive religion, drowned out in recent decades by the well-organized religious right, has been revived by the rise of President Trump. Within weeks of the 2016 election, left-leaning religious groups saw spikes in funding. Their coalitions became a crucial part of the “resistance” to Trump’s travel ban, the repeal of the ACA and the separation of families along the U.S.-Mexico border. Leaders such as Barber and Linda Sarsour, a prominent Muslim activist and core organizer of the Women’s March, have been elevated to the national stage.

As their influence increased, so too did side-by-side appearances with potential 2020 presidential hopefuls such as Booker, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass.; Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif.; and others.

For modern religious progressives the new attention comes with a dilemma: What does it mean not only to protest power but to influence it — or even be courted by it?

“I think faith communities, particularly the religious left, need to become even more aware of the significant, for lack of a better word, lobbying power that they have,” said the Rev. Kelly Brown Douglas, a theology professor and dean of Episcopal Divinity School at Union Theological Seminary in New York.

Marie Griffith, director of the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University in St. Louis, said the shift harks back to the era of President Carter, who ran as a Southern Baptist Democrat.

“I would absolutely see (Carter) as exemplifying this progressive Christian vision,” she said, noting that after he lost re-election the progressive religious spirit that elected him “went underground.” In a sense, the rise of Bookers and Barbers signals a return to form.

“They’ve got their boldness back, and they’re willing to speak in the name of religion and not hide their light under a bushel,” she said.

Douglas also highlighted the importance of Booker’s attachment to the black church.

“Historically, black communities have relied on the leadership and the wisdom of their faith leaders,” she said.

It’s unclear whether white Democrats of faith, whose numbers continue to dwindle, can be successfully courted along faith lines, despite numerous attempts over the years by groups such as Sojourners and others. But appealing to the faith of nonwhite Democrats, according to data unveiled earlier this year by Pew Research, suggests that may be a crucial long-term strategy for those seeking to turn red states blue. Although states with higher religious attendance and expression tend to be Republican, nonwhite populations in those states skew highly religious and deeply Democratic.

Douglas pointed out that Booker already exhibited the power of the black faith community in the 2017 Alabama senate race. As Republican Roy Moore battled accusations of child sex abuse, Democrat Doug Jones reached out to black voters, using the last days before the election to campaign at several black churches.

Standing next to Jones during those church visits was Booker.

Two days later, analysts largely credited Jones’ victory to massive black voter turnout.

Preaching a new ‘civic gospel’

Booker is not the only potential presidential hopeful vying for the religious left’s attention. Warren, Harris and others are also winning hearts among the faithful. Booker has also faced hard questions from the left, including religious progressives, for taking large donations from Wall Street.

He’d likely also have to address the concerns of slightly less than a third of Democrats who do not claim a religious affiliation, many of whom are uneasy with politicians who cite faith as a guide.

Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., addresses Festival of Homiletics attendees at Metropolitan AME Church on May 22, 2018, in Washington. RNS photo by Jack Jenkins

But Booker is already working out ways to talk to them, too.

“I prefer to hang out with nice, kind atheists than mean Christians any day,” he has often said.

Meanwhile, the larger struggle may be to convert the religious left into an organized political force.

Gregory identifies “a kind of paralyzing despair or prophetic critique that disables the possibility of politics more than enabling it. In some ways, I think one of the reasons why Senator Booker often gets a lot of enthusiastic reception is because he is capable of recognizing severe challenges but also not giving in to the despair or withdrawal.”

Booker’s optimism is embodied in his concept of a “civic gospel,” a vision for a politics devoid of the “meanness” and “moral vandalism” that he sees in current political discourse, especially from Trump.

“I think God is love,” Booker said, leaning across his desk. “I think God is justice. I think that the ideals of this country are in line with my faith. I don’t need to talk about religion to talk about those ideals that all Americans hold dear.”

Perhaps Booker is something of an evangelical — or at least an evangelist — for this ecumenical sense that politics and religion are not mutually exclusive, all while reaching those outside the religious fold with a broader inclusive message. Whether the faithful, literal and figurative, will rally around that idea will likely be the question of his next two years.

“Every speech I give, I will not yield from talking about that revival of civic grace,” he said.